Introduction

Modern Biblical scholarship has concluded that the majority of what we now have in the Biblical Pentateuch was substantially written in the seventh to fifth centuries BC. This creates a formidable problem for the traditionalist view (of both Jews and Christians) that holds that these foundational works were written by Moses, in Moses’ timeframe. But should it?

How to Think About the Provenance of the Pentateuch

I realize that the vast majority of Christians and Jews not only accept on faith that Moses wrote the five books of the Pentateuch, but that anyone who disputes this belief is thought to be attacking the faith itself. The traditionalists feel justified in their conclusion as many of the contemporary Biblical scholars who study these texts do not believe as they do. Many are, in fact, atheists.

But, it is crucially important to distinguish between the personal views of these scholars and the result of their work – the data that they have extracted from their study of the texts. The questions we, as believers, need to develop thoughtful answers to include:

- If books of the Pentateuch contain passages that indicate that a passage was a later insertion into a former text, how should we incorporate that fact into our thinking?

- If some of the books of the Pentateuch are, from a writing style perspective, virtually identical to the writing style and phraseology of books written much later in Israel’s history, how should we account for that fact?

- If some of these same books of the Pentateuch proclaim that they contain the words of God spoken to Moses (and/or Aaron), how should we understand the thinking of their authors, whenever these books were written?

- The Hebrew Bible is full of references to “the Law of Moses” and similar terms, all pointing back to an ancient scroll, attributed to Moses and containing the rules and precepts specified by God for how the nation of Israel should live in the land He was giving them. Assuming such a scroll was produced, what did/does it consist of? And can we find it in the version of the Pentateuch we have today?

- If the Moses Scroll exists and we can identify it (all or part); and if it differs fundamentally on common points with other books of the Pentateuch, how shall we view those other books, remembering that they all bear the presumption of Moses’ (and God’s) authority in their creation?

To review, we have two drastically opposed views of the development of the Pentateuch. In one, Moses was given the instructions (Torah) of God, which he then wrote down. This view sees the entirety of the Pentateuch (Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy) as Moses’ Torah.

In the other view, Moses may have been given God’s instructions to Israel for living in the land, but those instructions were not the entire Pentateuch. The key evidence we have for this is the statement in Ne 8:3 that it took Ezra “from early morning until midday” to read Moses’ scroll to those assembled in Jerusalem. To read aloud the entire Pentateuch would require much more than a morning – something closer to twenty hours (at 130 words/minute), in fact. On the other hand, reading Deuteronomy aloud, as we have it today, would only take 3.6 hours at the same rate.

Evidence for the Nature of Scriptural Development in Ancient Israel

Biblical scholars are in near-unanimous agreement that the books of the Pentateuch were substantially written in the period between the seventh century BC and the fifth century BC, essentially encompassing the Babylonian exile and its return.

This would mean that the books of the Pentateuch were written late compared to the narrative they describe. But we should not be surprised by this, nor dismayed. The Israelites did not think about their scriptures in nearly the way we do today. We see the Bible in its entirety as iviolable because it is a finished work, and has been for 1700 years or so. Not so the ancient Israelites in their day.

In researching this piece I have come to understand the attitude, or mentality, of early Hebrews concerning writing down their recollections of the “events” of their past. Their thinking was not what we in the modern West would bring to the task – that of accurately recording the exact sequence of events that occurred, and only later, perhaps, casting them into an ideological or mythic interpretation.

That’s not, apparently[i], how the Israelites thought about telling their story. Unlike us, they didn’t approach their history as a discreet set of facts to uncover and explicate. Rather, they approached their history as a narrative founded on a few core ideas (e.g. their God as the highest God, God electing Abraham and Israel; God redeeming Israel from Egyptian bondage; God choosing Moses to be His prophet; God giving Israel its land and covenant, etc.) How any of those things actually happened was of little concern to the ancient (or later Rabbinic or modern) Jew.

This can sound outrageous to those who know something about Israel’s veneration of their story and their Torah. But what we have to recognize as moderns is that until the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) was actually considered a “canon” (sometime following the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD), Jewish priests and scribes were in a continuous process of refining and exegeting the old texts/memories (primarily the Writings and Prophets rather than the Pentateuch[ii]) to better and more convincingly portray their core ideas within their mythic stories[iii].

I know for myself, having seen a couple of documentaries on the Jewish scripture-copying process[iv] of counting letters per line/column and similar quantitative techniques to guarantee that what was copied was precisely what was in the scroll being copied, I had thought that their commitment to the original was exemplary. What I didn’t realize was that this practice was only adopted once the canon was complete and there was something immutable to be accurately preserved.

If there ever were ancient (i.e. Mt. Sinai/Moab) texts, what they actually said was conveyed down through the generations in terms of what the previous generation remembered about what they contained. The texts themselves were closely held by their (literate) authors. The overriding motivation for elaborating the ancient texts/memories was not to improve their historicity or accuracy. They didn’t really care about accurate details. They only cared about promoting/enhancing those narratives through their elaboration and integration into what would become the final corpus[v].

This brings us to a little-recognized (outside of scholarly circles) characteristic of early Hebrew itself. Early (i.e. “paleo-“) Hebrew was a language exclusively of consonants. As pointed out by Schorch[vi], the language in its consonantal purity could not unambiguously communicate the meaning intended by the author’s written words. Rather, the author (or someone who had heard him recite his text) would have to speak his text in order for a reader of the text to unambiguously understand what the author had written.

The missing elements of the consonantal framework of the text necessary to convey its intended meaning were the vocalizations (e.g. which vowels were used), punctuation, and paragraphing that would be added later. The referencevi (p361-363) contains two separate examples of ambiguity you should review: one having to do with ambiguous vocalization, and one having to do with missing punctuation.

The takeaway from this ambiguity, as Schorch points out, is this: if the reader of a text knew its vocalization and punctuation from hearing it read, then in his own reading he applied this additional information to result in reproducing the author’s original meaning. If, however, the reader of a text did not know its vocalization or punctuation from a previous hearing, he was left to his own devices to try to infer the vocalization (e.g. which vowels), punctuation, and thus the original meaning of the text, sometimes coming up with a conclusion different than that which the author intended. This reader would create his own meaning. But as long as his meaning venerated the meta-story of Israel, it became an accepted variant.

Variants in the Biblical narratives are a fact of the Hebrew Bible. If you doubt this, you can do your own research on a single topic, e.g. the Ten Commandments, and see the extent to which the ancient authors of Exodus and Deuteronomy agree on what they were[vii]. That these books are part of the accepted canon, with all of their inconsistencies, only testifies that the ancient authors didn’t care about precise details – only Israel’s overarching “story”[viii]. Who are we to claim that these ancient authors weren’t “inspired”?

Oral Transmission of Israel’s Mythic Traditions

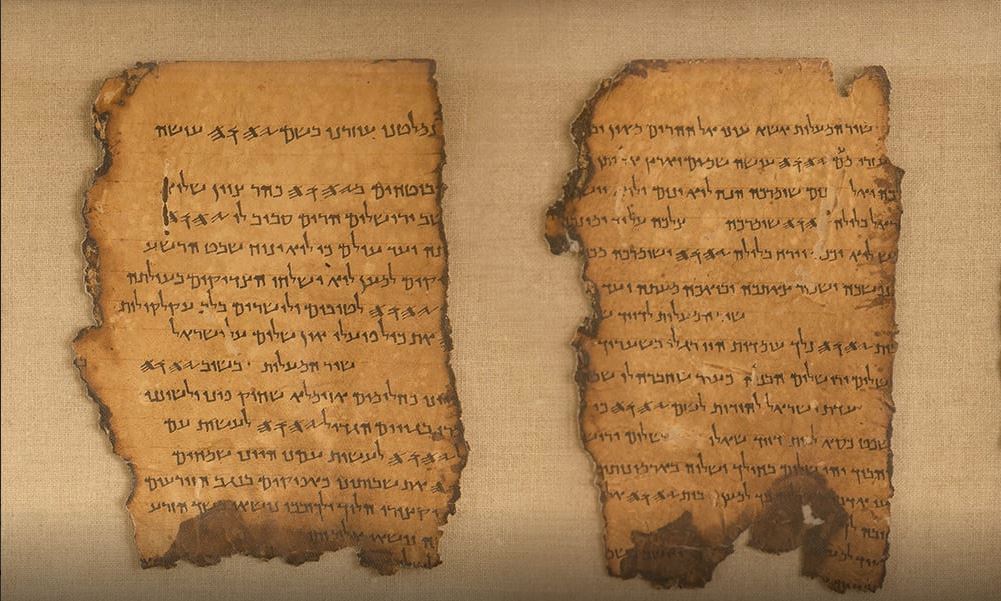

The fundamental problem everyone has in trying to reconstruct the history of the Pentateuch is that we have no corroborating evidence of its Torah texts until we get to the Desert Scrolls and Qumran dating to between 250 BC and 100 AD. How did they get there?

The common narrative is that they were faithfully handed down, unchanging from generation to generation, through the priests. And there is some support for this view, particularly for Deuteronomy.

In 2 Kings 22:8 we have the account of Hilkiah, the High Priest, finding Moses’ law scroll in the Temple:

And Hilkiah the high priest said to Shaphan the secretary, “I have found the Book of the Law (or “Scroll of Instruction”: “Sefer HaTorah”) in the house of the LORD.” And Hilkiah gave the book to Shaphan, and he read it.

The date of this “discovery” would have been approximately 625 BC during the reign of Josiah. According to the Biblical story, Josiah then reads the scroll and is immediately undone, recognizing that Israel has not been following the instructions given to Moses by YHWH some 600-800 years previous.

Modern biblical scholars tend to dismiss the biblical story out of hand (“how could you NOT know where in the Temple the Scroll of Moses was kept?!”), and instead attribute it, including what we can only surmise is a large swath of the Book of Deuteronomy, to Josiah’s authorship in support of his goal of reforming Israel’s worship practices to their centralization in Jerusalem at the Temple.

What’s questionable about this story is that Deuteronomy (in which I believe we have as close as we’re going to get to Moses’ original scroll from Moab (Deut 31:9, 24-26)), actually isn’t emphatic about centralizing worship in a single location – ultimately Josiah’s Jerusalem. It is concerned with worshipping only at “the place the LORD your God will choose” (Deut 12:11). Furthermore, Deut 27:4-8 refers to sacrifices on Mt. Ebal, in the center of what would become Samaria, certainly a place far different than Jerusalem.

So if Josiah actually did write what we’re told is the “Book of the Law”, he certainly did a good job of trying to cover his tracks, at least on this point. We should also note that the Bible claims in 2 Ch 34:3-14 that Josiah had already been instituting his reforms for six years at the point when the scroll was reportedly found. So at the very least, it seems the scroll wasn’t the cause of the reforms. Perhaps the reforms, including the cleansing/purifying of the physical Temple, were actually the cause of rediscovering the scroll?

Table 1[ix] depicts the similarities between Josiah’s reforms and their specification in Deuteronomy.

What, then, might have inspired Josiah’s reforms? He no doubt recalled his great-grandfather Hezekiah’s (716-687 BC) successful reforms a century earlier. Hezekiah was convicted of the threat to Judah in light of apostate Israel’s defeat and expulsion from their land by the Assyrians. God subsequently spared Jerusalem from destruction by the Assyrians. Now Josiah’s Judah is being besieged by the Babylonians and facing potentially the same fate. So it is hardly unexpected that Josiah would recognize that a) Judah had been engaged in activities prohibited by Moses’ Book of the Law, like his brothers in the north had been, and b) their only hope of eliciting God’s mercy on them and avoiding destruction was to reform those activities.

If the Hilkiah story is true (and not, like so many would have us conclude, merely an allegory of reinstating what was then known orally of Moses’ Law), then obviously the only way to transmit it down through the centuries would have been by the oral retelling of what each generation remembered of its content. For example, David (1000 BC) refers to it in 1 Ki 2:2-3 as he admonishes Solomon to adhere to all that is “written in the Law of Moses”.

Jehoshaphat (870-848 BC) knew something of Moses’ Law as is mentioned in 2 Ch 17:9. Apparently, he was having it taught throughout Judah:

[9] And they taught in Judah, having the Book of the Law of the LORD with them. They went about through all the cities of Judah and taught among the people.

although exactly what they then thought of as “the Book of the Law of the LORD” isn’t perfectly clear.

And we have this, speaking of Jehoiada (842-796 BC) following its instruction; 2 Ch 23:18:

[18] And Jehoiada posted watchmen for the house of the LORD under the direction of the Levitical priests and the Levites whom David had organized to be in charge of the house of the LORD, to offer burnt offerings to the LORD, as it is written in the Law of Moses, with rejoicing and with singing, according to the order of David.

Interesting that it says “as it is written in the Law of Moses”.

Finally, we have the scriptural evidence of 2 Kings 14:6 (and 2 Chr 25:4) reciting a fragment of Moses’ law and speaking of King Amaziah:

[6] But he did not put to death the children of the murderers, according to what is written in the Book of the Law of Moses, where the LORD commanded, “Fathers shall not be put to death because of their children, nor shall children be put to death because of their fathers. But each one shall die for his own sin.”

This seems to be quite literally cited from Dt 24:16:

[16] “Fathers shall not be put to death because of their children, nor shall children be put to death because of their fathers. Each one shall be put to death for his own sin.

King Amaziah ruled from 796 BC to 767 BC. So the scroll of Moses (or at least the memory of this particular instruction it contained) had to have been available to the King during his reign.

These references all predate the Hilkiah event by more than a hundred years. Were they just “remembering” the Scroll of Moses based on what had been passed down orally? Or, was the scroll always at hand (despite a dearth of references to it after Joshua)? Or, was the scroll available until sometime in the eighth century (when, by the way, the apostasy to Baal and Asherah and high-place worship surged – possibly during the reign of Manasseh) at which point it disappeared for a hundred or so years before again being “found”?

“The Place that God Will Choose”

Schorchvi inadvertently gives us a fact pointing to the scroll’s presence probably as early as the 10th century. In it he raises the importance of the phrase “the place that the Lord (your God) will choose” to Deuteronomy’s author:

‘The question of God’s chosen place is one of the central issues with which the book of Deuteronomy is concerned. Thus, in chapters 12 and 14–18 Deuteronomy refers no less than 22 times to “the place that the Lord (your God) will choose” (יתות המקום שה’ יבחר).’

He goes on to explain that there existed two interpretations of this key phrase; one that eventually ended up in the Hebrew Masoretic Text (“will choose”), and one that was included in the Samaritan Pentateuch (“chose”). To the Samaritans, the choice of the location for sacrifice/worship was established by God in Gen 12:7 when He told Abram to erect an altar near Mt. Gerizim, at Elon Moreh/Shechem. They also cite God’s command to Israel to build an altar on Mt. Ebal (Deut 27:4-5) upon entering the land, that is, along with the adjacent Mt. Gerizim (overlooking Shechem), the site where Israel was commanded to hear the readings of the blessings and curses (Deut. 11:29).

Schorch’s point is that two different groups – the Judeans and the Israelites – told themselves the same text, but interpreted it slightly differently. But our takeaway here is that the basic text they were both referring to had to have been available to both groups at least shortly after the Israelites split off from the Judeans, in 922 BC. Why did the Israelites (the northern Kingdom) begin worshipping on Mt. Gerizim in the 10th century BC? Because they had and read (albeit their way) Deuteronomy.

I’m going to stick with the Bible on this one[x] — that God did indeed transmit His “instructions”, His Torah, to the prophet Moses, but that it was at some point misplaced (possibly due to the pollution of the Temple with foreign idol worship under an apostate Judahite King) before being rediscovered in roughly 625 BC.

The Narrative of the Books

Here we’re only going to concern ourselves with Numbers, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy, not Genesis nor Exodus. Why? The narrative of Genesis is not something an eyewitness is claimed to have written. And, with Exodus, while it certainly could have been written by Moses, it nowhere claims that. In fact Exodus (like the other non-Deuteronomic books of the Pentateuch) always refers to Moses in the third-person voice, as if its author was an observer of Moses, or, perhaps, one who is remembering what eyewitnesses related about the story. Why would Moses write one scroll in his first-person voice, but others in the third-person? Let’s do a quick survey of the key features of these three books.

Numbers

Numbers is a strange book. It vacillates between historical narrative, often tracking Exodus, and provisions that have been clearly authored by Priests, defining in meticulous detail how and when various sacrifices were to be offered. In trying to understand the purpose of the book, scholars[xi] have recently proposed its principal purpose is to both announce God’s judgment on the Exodus generation; Num 14:28-30:

[28] Say to them, ‘As I live, declares the LORD, what you have said in my hearing I will do to you: [29] your dead bodies shall fall in this wilderness, and of all your number, listed in the census from twenty years old and upward, who have grumbled against me, [30] not one shall come into the land where I swore that I would make you dwell, except Caleb the son of Jephunneh and Joshua the son of Nun.

and the fulfillment of that judgment, following its second census of Israel, Num 29:64:

[64] But among these there was not one of those listed by Moses and Aaron the priest, who had listed the people of Israel in the wilderness of Sinai. [65] For the LORD had said of them, “They shall die in the wilderness.” Not one of them was left, except Caleb the son of Jephunneh and Joshua the son of Nun.

This is very much in the style of Genesis’ “creation (exodus) – de-creation (exodus generation dies off – in a plague and over time) – re-creation (the new generation)” narratives. We should also note that Numbers also claims the beginning of the fulfillment of the land prophesies God promised, starting with Abraham (Num 21:24-25).

As likely a purely literary device, the Book of Numbers tells the story of Balak, King of Moab, and his hiring of the prophet Balaam to curse Israel as they were camped at the edge of his land. Explaining this story would have been a requirement for later editors of the Pentateuch to account for Deuteronomy’s reference to it in Dt. 23:4-5, and explaining why the Amorites and Moabites were deserving of being displaced from their land and rightfully replaced by Israelites.

But it’s very important, I think, that the book documents an institutional distinction between common Levites, and the Kohanim – descendants of Aaron. The book tells of the rebellion of the elders of Israel, represented by their spokesman Korah, a Levite, against Moses’ and Aaron’s priestly hierarchy (who, of course, were also Levites). Where once Moses treated all Levites as “priestly Levites” (Dt 18:1-8) now, for some unexplained reason, they are merely Tabernacle/Temple workers, excluded from offering sacrifices that have become the exclusive duty of those Levites who are descended from Aaron. So Korah protests: Numbers 16:3

[3] They assembled themselves together against Moses and against Aaron and said to them, “You have gone too far! For all in the congregation are holy, every one of them, and the LORD is among them. Why then do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of the LORD?”

God had commissioned the entire nation of Israel to be a kingdom of priests – a “holy nation” in Ex 19:5. After the calf incident, the sons of Levi step forward to show their devotion to YHWH (Ex 32:25-29), the result of which is that God ordains the Levites to his service (v29). (Levites are commissioned by God to his service in place of the offering of people’s firstborn sons to God’s service.)

However, what we have at the completion of the Korah “rebellion” is God using the earth to swallow up Korah and the other rebellious Levites.

It’s important to acknowledge that the Bible offers no explanation for this shift from “all the tribe of Levi” to “sons of Aaron”[xii]. It wasn’t the protest of Korah that caused the change. Korah was protesting the change. If God had an explanation for it, He would, it seems to me, have included it in His scriptures. Since He doesn’t say anything about it, we should be quite dubious about its origin. If God doesn’t bother to explain it, maybe it wasn’t His doing in the first place?

What’s so truly bizarre about this story, in addition to God not offering any explanation, is that their father, Aaron, was a key ring leader in the molten calf incident, an event that is probably the poster child for Israel’s willful disobedience. (Afterwards, he also lies to Moses about it: Ex 32:24: “So I said to them, ‘Let any who have gold take it off.’ So they gave it to me, and I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf.”)

It is true that we get a narrative in Lev 8 and 9 in which Moses reports that he has been commanded by God to anoint the tabernacle, its altar, and ordain Aaron and his sons as priests in front of the Tabernacle and all the people. But God’s scripture offers us no explanation whatsoever for this fairly dramatic turn of events. And, we should note, Moses’ declaration of the Levites being “priestly Levites” occurs chronologically 39 years or so after the reported ordination of Aaron and the Kohanim in Exodus 29. Strange. Maybe there is no divine explanation?

Leviticus

Contrary to what we might expect given its name, the Book of Leviticus has virtually no mention of Levites and their role in the nation. (The Book of Exodus has one, mentioned above.)

Scholars tell us that Leviticus was written by two different types of authors; “P” for Priestly (of which there are at least three), and “H” for holiness[xiii]. Lev 1-16 are thought to be authored by the P author(s); they identify the priests as those of Israel that are holy. Lev 17-27, thought to be authored by the H source, claims that all Israel should aspire to holiness (“be holy as I am holy”). He says God declared (demarcated) the Sabbath as holy, but it is Israel who proclaims its holiness through their observance/actualization of it.

Leviticus seems to conceive of God as immortal and asexual. So to have communion with Him, one needs to be purified from contact with death and sex acts. This is why most of the purification rituals of Leviticus have to do with cleansing the one who seeks to be in God’s presence in the temple/tabernacle from contact/proximity to these two conditions.

The offerings of the ritually pure (meaning qualified to come into contact with the holy) were offered by all Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) cultures to gain God’s favor, to ensure that he was favorably disposed to both the offeror and his people. They have nothing to do with atoning for sin.

Moral impurity is one’s state following murder, forbidden sexual activity, idolatry, etc. Repeated acts that create moral impurity can defile the holy things (sancta) and, eventually, the land itself. The penalty for murder, idolatry and sexual transgression is death: there is no prescription to purify such people.

Other moral impurity offenses require confession and repentance by the offender before he can be re-purified. (NOTE: There is no expiation for intentional sin in the Hebrew Bible. Violators are just disbarred from Israel or killed. The Atonement (Yom Kippur) is a cleansing only of unintentional sins of the people. The thinking seems to be based on knowing that God wants obedient hearts in His children. They surely didn’t want to implement a system that restored a purposely disobedient yet unrepentant person to fellowship with the people, and with God, as that would institutionalize accommodation of sin that caused moral impurity.)

Once a year the temple had to be purified to cleanse it (in order for God to continue to inhabit it) from all the sins of the people that were unacknowledged. In his authoritative commentary on Leviticus[xiv], Jacob Milgrom’s thinking is that Israelites thought that if these sins weren’t periodically purged from the temple, (and from the people via the scapegoat), God would eventually be forced out by the accumulated sin, leaving Israel on their own, without the One to protect and bless them. Sin pollutes/scars the “sanctuary”, forcing Him farther and farther away. So people (in this case the priests) have to take responsibility for purifying God’s habitation and themselves – that’s not God’s job. Individual sin pollutes the entire society.

Many of these laws, then, were designed to keep God close to the nation. The food laws tended to restrict what Israel could eat to cows, goats and sheep, and whatever plants grew. They specified the (painless) slaughtering of the animals and the preservation of their blood – their life – for God. These laws may not have had any functional (e.g. health or hygiene) basis. But they did serve to set Israel apart from all other peoples.

So the gist of Leviticus is a very detailed, very specific set of instructions for carrying out the sacrificial system of the tabernacle on behalf of Israel. The purpose of this system is to maintain the cleanliness/purity of both the tabernacle itself (as God’s home) and of the Israelites in whose presence God lives. The question we have to wrestle with is, does this system sound like something the God of Moses would have prescribed (particularly in light of later Prophets’ complaints[xv] that it was not at all what God was interested in — (1 Sam 15:22, Ps 40:6, Is 1:11-17, Je 7:22, Ho 6:6, Mi 6:6-8))?

What’s quite remarkable in examining Numbers and Leviticus is that neither contains a single reference to the “Law”/”scroll”/”book” of Moses nor to the ”Book of the Law”. Especially for the book of Numbers, with its narrative taking us up to and, indeed, into the land, one would expect some allusion to the instructions given by God to Israel through Moses for how they were to live in that land. But we find nothing.

Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy is a recapitulation of God’s covenant with Israel, initially given to Moses at Mt. Sinai/Horeb. It is written in the form of a late second-millennium Hittite suzerainty treaty in which a powerful state decrees to an autonomous vassal state its duties and obligations to the sovereign[xvi]. (The suzerainty treaty format is one of the only arguments for a 2nd millennium BC dating of the book.) In Deuteronomy, God is the sovereign actor and Israel is the vassal state. In it He says:

- What God has done for them beforehand (Exodus, sustainment in the wilderness, etc.) Dt 1:6-4:49

- God’s general stipulations on Israel (e.g. the Ten Words, the Shema, God’s character, etc.) Dt 5-11

- Detailed Stipulations (a recapitulation [insertion?] of the instructions given to Moses by YHWH at Horeb and Moab: Dt 12-26[xxiii]

- Blessing and Curses – Dt 27-28

- Witnesses: Dt 4:26; 30:19, 32

Such treaties outlined what would happen to the vassals if they disobeyed the sovereign, and what they would gain if they obeyed. Deuteronomy is the only book to contain (or even mention) as a component of the covenant law an itemization of the curses they would incur if they disobeyed. (These curses are, no doubt, what devastated Josiah upon his reading of the scroll).

Whatever its organization, it is widely held that the content of Deuteronomy is the foundation in establishing the narrative of Israel’s history that carries on in a conformant style throughout Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings – the so-called “Deuteromistic History”.

But this foundational history is not Deuteronomy’s only distinctive among its Pentateuchal cohort.

Deuteronomy’s Distinctives

First-Person

For one, Deuteronomy is the only book of the Pentateuch that contains the words of Moses in the first-person voice. So you might respond, “Well, anybody could decide to write a narrative in the voice of somebody else.” And, of course, that’s true.

But why would the redactors of the Pentateuch allow this book to retain its first-person voice, and a voice that disputes some of the priests’ most revered tenets?

It seems the simplest answer is that it is the voice of Moses, the greatest prophet in Israel of all time, as attested by a later (anachronistic) editor of Deuteronomy (34:10-12):

10Since that time, no prophet has risen in Israel like Moses, whom the LORD knew face to face— 11no prophet who did all the signs and wonders that the LORD sent Moses to do in the land of Egypt to Pharaoh and to all his officials and all his land, 12and no prophet who performed all the mighty acts of power and awesome deeds that Moses did in the sight of all Israel.

The towering stature of Moses carried overwhelming authority with later editors of the Pentateuch, so much so (I speculate), that despite the fact that some of Moses’ Torah contained points of emphasis not found in the other books, his singular authority as the source of these instructions convinced those later editors to preserve them in Moses’ own voice.

Furthermore, Deuteronomy (31:9, 31:24) itself claims Moses authored God’s Torah in Moab shortly before his death.

The Law

Deuteronomy restates the laws given to Moses by God at Mt. Horeb. It then goes on to expand those laws into applications for Israel as they enter into and live within the land God promised their fathers. The Horeb commands, Deuteronomy’s recapitulation, and then expansion of them is depicted in the following table[xvii].

Now it is true that Numbers and Leviticus do contain some instructions for the people. For example, Leviticus 17-26, identified earlier as the “Holiness Code”. These chapters exhort the Israelites themselves to live holy lives through moral and ethical principles of living, rather than its earlier emphasis on the priestly sacrificial responsibilities in support of preserving God’s presence (heaven) on earth (in Israel’s camp and tabernacle).

Numbers is largely a retrospective of Israel’s history to the point of entering the land. It reinforces some instructions given elsewhere, re: some sacrifices; keeping vows, etc. It does not contain instructions to the Israelites, per se, for living in the land. And, it certainly contains no mention of Moses’ Torah[xviii].

Moses’ Call to Devotion to God

Deuteronomy is unique not only in its call to devotion to the LORD but in the phrasing of its exhortation: “You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might/everything” (Deu 6:5, Deu 26:16, Deu 30:6). Deuteronomy here appeals to Israel’s heartfelt devotion, not simply their rote obedience.

In Exodus, by contrast, we hear a much different appeal attributed to Moses. In Exodus 19:4-6 God speaks to Moses the admonition to obedience for Israel:

[4] ‘You yourselves have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself. [5] Now therefore, if you will indeed obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession among all peoples, for all the earth is mine; [6] and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.’ These are the words that you shall speak to the people of Israel.”

After YHWH recites His “Ten Words” to Israel at Sinai, the people react: Exodus 20:18-20

[18] Now when all the people saw the thunder and the flashes of lightning and the sound of the trumpet and the mountain smoking, the people were afraid and trembled, and they stood far off [19] and said to Moses, “You speak to us, and we will listen; but do not let God speak to us, lest we die.” [20] Moses said to the people, “Do not fear, for God has come to test you, that the fear of him may be before you, that you may not sin.”

Here we have the author quoting Moses delivering a completely different message. Here the message is not “love Me with all of your everything” but rather “Obey Me”; Don’t love God but “fear Him so that you won’t sin.” Forgetting for a moment what we know of the paleo-Hebrew scrolls of these scriptures found at Qumran, their virtually undisputed late redaction long after the events they relate, we have to recognize that there are two fundamentally different messages being conveyed by these two books, whoever and whenever their authors were.

Israel’s Support of the Levites, Sojourners, Widows, Orphans, the Fatherless

The author of Deuteronomy is insistent on the privilege of the Levites in being the recipients of the sustenance provided by the wider community of Israelites in recognition of their service to God on their behalf in His Tabernacle. This theme is in stark contrast to the Levites’ treatment in Leviticus and even Numbers. There, while they get some acknowledgment as privileged by God (e.g. Num 8:5-26, Lev 25:33), they are clearly secondary to the Aaronic priesthood.

In Deuteronomy, the Levites are not so much revered as a holy priesthood as they are called out for the same charity that the Israelites are commanded to extend to “the sojourner, the fatherless and the widow who are among you” (Dt 16:11). The author of Deuteronomy is preeminently concerned with Israel’s charity to both the disadvantaged among them (widows, orphans, sojourners, the fatherless) and those designated by God to serve Him on their behalf, and so not sharing in the other tribes of Israel’s land inheritance.

This is a key distinctive of Deuteronomy. A reference to one or more of these words in the context of God’s concern for Israel’s provision for them occurs no times in Genesis, 3 times in Exodus, 3 times in Leviticus, no times in Numbers, and fourteen times in Deuteronomy. The point of this is simply that God’s heart for those in need (God’s “social justice”) was a key theme of Deuteronomy, but of only casual, if any, interest in the other books of the Pentateuch.

God’s Covenant with Israel

The entire premise of the story of Israel is that God had made a covenant with them at Sinai that if they obeyed His commands, they would be blessed, enter the land He gave them, and prosper, but if they ignored His commands, they would be cursed. Deuteronomy documents this covenant (Dt 4:1-43), and pays unique attention to its blessings and curses in chapters 27 and 28.

Exodus mentions the Mosaic covenant only 7 times.

Leviticus mentions a covenant of salt(2:13); bread (24:8) and then the Mosaic covenant 6 times, all in chapter 26 (9, 15, 25, 42, 44-45)

Numbers never mentions it, but instead speaks of, e.g., a covenant with Aaron’s sons as a perpetual priesthood.

Deuteronomy refers to it 25 times. The author of Deuteronomy saw God’s relationship with Israel in its covenantal context, not as something unilateral.

Tithes (Maaser)

Deuteronomy addresses the practice of tithing to God. In Deut 26:12 it says:

[12] “When you have finished paying all the tithe of your produce in the third year, which is the year of tithing, giving it to the Levite, the sojourner, the fatherless, and the widow, so that they may eat within your towns and be filled

That’s pretty clear. But it is explicitly contradicted by Numbers’ prescription for the same practice in Num 18:24:

[24] For the tithe of the people of Israel, which they present as a contribution to the LORD, I have given to the Levites for an inheritance. Therefore I have said of them that they shall have no inheritance among the people of Israel.”

Here it seems the Levites are the exclusive recipients of tithes.

Firstborn Animals

Deuteronomy specifies that the firstborn male animals of the Israelites are to be offered to the LORD and eaten by them and their families, Deut 15:19-20:

[19] “All the firstborn males that are born of your herd and flock you shall dedicate to the LORD your God. You shall do no work with the firstborn of your herd, nor shear the firstborn of your flock. [20] You shall eat it, you and your household, before the LORD your God year by year at the place that the LORD will choose.

Once again, however, Numbers sees it differently. In Num 18:17-19 we read God speaking to Aaron the High Priest:

[17] But the firstborn of a cow, or the firstborn of a sheep, or the firstborn of a goat, you shall not redeem; they are holy. You shall sprinkle their blood on the altar and shall burn their fat as a food offering, with a pleasing aroma to the LORD. [18] But their flesh shall be yours, as the breast that is waved and as the right thigh are yours. [19] All the holy contributions that the people of Israel present to the LORD I give to you, and to your sons and daughters with you, as a perpetual due. It is a covenant of salt forever before the LORD for you and for your offspring with you.”

So it seems someone has co-opted Moses’ instructions and redirected the sacrificed firstborn animals away from their owners to the priests with no explanation. Strange.

Sabbath Observance

In Deuteronomy (5:14) the author explains that the reason Israel is to observe the Sabbath day of rest is that they and their “male and female servants may rest as well as you”. In Exodus, however, the Sabbath is given a different meaning. There (Ex 20:11) God explains that the Sabbath is to be observed because “the LORD rested on the seventh day” after He created.

There are many other discrepancies between Deuteronomy and the other books of the Pentateuch. But these, hopefully, give you a sense of the character of their respective authors. Deuteronomy seems to evoke a certain reverence, humility, and humanity in detailing his prescriptions which are just not present in the other books.

Even Leviticus’ statement of what Christ called the second of the two most important commandments in the Bible (Mt 22:37-39) seems to come across as almost an afterthought (Lev 19:18):

[18] You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against the sons of your own people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.

When Were The Books of the Pentateuch Written?

As noted earlier, the majority of Hebrew Bible scholars today have concluded that the books of the Pentateuch were written centuries after the historical narratives they relate. How do the experts determine this?

One of the key techniques involves identifying words contained in a text that didn’t begin in usage before a certain date.

In the case of the Pentateuch there are several “5th centuryisms” contained in each (e.g. “prophet”, 5030. נָבִיא nāḇiy’); if the word wasn’t in use before the 5th century but is contained in these books, then at the very least the books were modified in the 5th century or later (following the exile), if not authored outright then (Gen 20:7, Ex 7:1, Num 12:6, Dt 13:1, etc.). Before the 5th century, prophets were known as “seers” (7200. רָאָה rā’āh, רׂאֶה rō’eh, as, e.g., in 1 Sam 9:5, 2 Sam 15:27, 1 Chr 9:22, etc). The possible conclusions are that these latter scriptures were written before, or at least not edited after the 5th century BC, or that they were, but for whatever reasons their authors elected to use the ancient term.

It is ambiguous, at the least, to note that the stylistic integrity of the books of the “deuteronomistic history” (i.e. Deuteronomy through Kings excepting Ruth) spans books some of which (Deuteronomy) use the 5th-century terms while others (Samuel, Kings) use the earlier “seers”.

In addition, scholars like to point to the stylistic similarity between the writing of Deuteronomy and Jeremiah, a seventh-century prophet. Thus, according to these scholars’ arguments, this implies Deuteronomy was a product of the seventh century (arguing, once again, for its authorship by Josiah or perhaps Hilkiah, his High Priest).

But others, assuming the veracity of the 2 Kings 22 story of finding Moses’ scroll, focus on the watershed moment this would have been for Jeremiah, Josiah’s contemporary. It’s easy to see how Jeremiah would have been led to proclaim the messages he saw in Moses’ scroll, for example, the Temple Sermon of Jeremiah 7 that illustrates his concern for the “sojourner, the orphan, and the widow” (Jer 7:6), a common Deuteronomic refrain (Deut 18:6; 23:8; 24:17; 27:19)[xix],[xx].

Why Is Deuteronomy Likely Substantially Authentic as “Moses’ Torah”?

First, let’s stipulate that there is no way, currently, to claim conclusively that Deuteronomy is substantially Moses’ Torah, or that it was authored by someone else centuries after Moses. Now, we’ve already pointed out that the preamble (through chapter 4) and particularly the final two chapters contain some third-person voice and anachronisms that indicate those chapters are later redactions by later authors.

The first and probably most significant piece of evidence for its authenticity is its use of Moses’ first-person narration. As noted, no other book of the Hebrew Bible does.

We certainly have several books that narrate a famous personality’s conversations. But they’re all done in the third person (e.g. “Job said”, “Ruth said”, “Saul said” [Samuel], “David said” [Samuel, Kings], etc).

Another significant trait of Deuteronomy’s authenticity is its persistent future-tense prophecies and warnings (by Moses) concerning what the Israelites will face and how they are to act when they enter the land in the coming weeks and months: fear God and be faithful, God will be with them to defeat all the people the Israelites are afraid of, don’t interact with the Canaanites, or worship their gods, etc.

And lastly, Deuteronomy alone spells out the details of the covenant God established with Israel, including how they would be blessed for their obedience and faithfulness, and how they would be cursed for their disobedience, which of course turned out to be prophetic. (Some might complain that Ex 34:10-26 also professes to be God’s covenant with Israel, at least as first delivered at Sinai. Scholars, however, see this as a later priestly ritual decalog[xxi].)

It seems reasonable that if God elected Israel out of slavery to serve Him, it would be very likely that He would spell out exactly what His conditional proposition to Israel was. And Deuteronomy, especially chapters 27-28, is exactly that.

What is the Case for Numbers and Leviticus Being Authentic?

I haven’t been able to find any support among scholars for the early (i.e. second-millennium BC) authorship of these books. They suffer from the presence of the same “5th-centuryisms” noted for Deuteronomy.

The feature of these books that is most puzzling as we discussed earlier is their complete dismissal of Deuteronomy’s “priestly Levites”, installing instead Aaron’s line as the exclusive priests. This just doesn’t sound to me like the way God would handle a transition like this (i.e. silence). Rather, it sounds much more like a late effort to undo, for whatever reason, the status of the Levites as a tribe of priests by descendants of Aaron who then saw themselves as the only ones qualified to carry out the sacrificial system they oversaw. In this scenario, Leviticus would have become the scriptural authority for their action.

For its part, Numbers appears to corroborate (not explain) the transition (e.g. Num 3) verbally transitioning them from “priestly Levites” to (Num 3:32);

[32] And Eleazar the son of Aaron the priest was to be chief over the chiefs of the Levites, and to have oversight of those who kept guard over the sanctuary.

When the most prominent method of providing emphasis to a point in the Hebrew Bible is repetition, it is just very unusual that not only don’t we have any repetition of the rationale for this significant change, we don’t have any rationale period. This is why I would conclude that it is a late, man-made change, not one implemented at Sinai.

I wonder, for example, why Jeremiah (8.8) has YHWH complaining: “the lying pen of the scribes has made it into a lie”? What was it that the scribes wrote that was, according to God, a lie?

What Does This All Mean?

The major takeaway for me in researching this piece was the realization that the Hebrew Bible wasn’t a “done deal” until likely the 70 AD destruction. The common assumption of laypeople is that the Bible was written at the time the events it describes happened. That’s most apparently challenged when considering Genesis. But scholars tell us their data shows edits/redactions being made to scriptures long after the events they relate occurred. (The Pentateuch books, perhaps predictably, were the most stable/least modified following the exile.)

A second major takeaway was the realization that not until the Roman destruction did Judaism become a “book religion”, rather than a religion of the Temple cult and their ritual practice. The main users of Jewish scripture before the destruction were the priests, the few elites during the monarchy, and the temple groups (e.g. Pharisees and Sadducees) in the 2nd Temple era. Early in their development, the priests were not just the near-exclusive users of the scriptural traditions they were handed, they were also their authors/editors that, compared to the population as a whole, comprised a tiny group.

Where did those scrolls of the Pentateuch found at Qumran come from? They were the product of centuries of contributions and redactions and verbal recitations that then were copied onto scrolls to be passed on to the next generation of priests and elites. (The oral/aural nature of the early texts was also a significant revelation for me.)

Does this model of the Hebrew Bible’s development challenge the traditional view of these texts? Yes, it does. But the issue, at its heart, is not the process or timeline of their development, but the presence of God’s hand in their creation – His inspiration of its authors. I find no reason that we should doubt God’s hand in crafting the Pentateuch and in fact, the entire Hebrew Bible, regardless of when He inspired those authors to contribute to its final form.

But it is also the case that early Israelites, in interpreting God’s revelation through their prophets and their circumstances, participated in formulating[xxii], and then codifying, their response to His revelation.

Conclusion

God provided special revelation to Moses outlining His covenant with Israel as a partial fulfillment of His covenant with their father Abram. The memory of the intimacy of this revelation is characterized as Moses speaking with God “face to face” (e.g. Num 12:8). The details of that covenant are remembered in Deuteronomy.

God, through Moses, revealed the principles of worshipping Him exclusively at the place(s) He named (and with the attitude of the heart He required), rather than worshipping false (pagan) gods “on every hill”. Israel’s implementation of this principle of central, monotheistic worship developed, over time, into the very detailed processes of the Temple cult enshrined in Leviticus (and chronicled in Numbers), just not as a result of God’s dictation of Leviticus to some priestly stenographer.

God’s covenant with elect Israel, despite Israel’s failure to fulfill their end of the bargain, ultimately produced the mechanism for blessing both Israelites and “the nations”, His Messiah. There is no more priesthood and there hasn’t been for nearly 2000 years. So it’s hardly consequential now whether or not the portions of the Pentateuch that enfranchised them turned out to be a collaborative effort between God and His prophets and priests, rather than unilateral dictation, as so many of us have been brought up to believe.

The fact that the non-Deuteronomic books of the Pentateuch exist today in the Hebrew Bible should inform the thoughtful reader that God had His own reasons for including them there, and their being thought of as authoritative for a people who were guided by their influence for some 1400 years.

[i] Memory in Ancient Israel | Marc Brettler – Academia.edu

[ii] “2.1. Textual History of the Pentateuch,” in Textual History of the Bible, vol. 1B, Pentateuch, Former and Latter Prophets (ed. Armin Lange and Emanuel Tov; Leiden: Brill, 2017), 3–21 (last proofs) | Emanuel Tov – Academia.edu

[iii] IBID, p9: “In the context of the Passover Haggadah, this midrash is probably to be connected to the earlier statement, “the more one tells about the exodus, the better,” where the word, “to do more,” is taken playfully as “to multiply”. This yields “the more one multiplies in relation to the telling of the exodus, the better.”

[iv] Process of copying the Old Testament by Jewish Scribes (scottmanning.com)

[v] “2.1. Textual History of the Pentateuch”, p10: “Lowenthal here emphasizes how and why memory, in contrast to the real past, typically changes. This is done, he notes, especially in traditional societies, but in ours as well “to validate the present. ” Lowenthal notes that “survival requires an inheritable culture, but it must be malleable as well as stable” 56 and “[t]he prime function of memory, then, is not to preserve the past but to adapt it so as to enrich and manipulate the present”

[vi] Schorch, Stefan: Which Bible, Whose Text? Biblical Theologies in Light of the Textual History of the Hebrew Bible. In: Assel, Heinrich / Beyerle, Stefan / Böttrich, Christfried (eds.): Beyond Biblical Theologies. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012 (WUNT; 295), 359–374.

[vii] A Comparison of the Ten Words in English with Explanatory Notes | Ross K Nichols – Academia.edu

[viii] This phenomenon of narrative enhancement I believe we’ve seen previously in the description of the conquest narratives, that I’ve written about here: https://saludovencedores.com/searching-for-a-consistent-biblical-god/

[ix] The Book of Deuteronomy | Rob Bradshaw – Academia.edu

[x] The Book of Josiah’s Reform | Bible.org

[xi] The Book of Numbers as the “Quintessence of the Torah”. Reflections on the Structure of the Fourth Book of Moses

[xii] The Levite Rebellion Against the Priesthood: Why Were We Demoted? Puzzling History of Leviticus 11 | Naphtali Meshel – Academia.edu

[xiv] Leviticus 1-16 (The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries): Milgrom, Jacob: 9780300139402: AmazonSmile: Books

[xv] 1 Sam 15:22, Ps 40:6, Is 1:11-17, Je 7:22, Ho 6:6, Mi 6:6-8

[xvi] This is a debated point in Biblical scholarship, first proposed by Kenneth Kitchen. Many other scholars see the organization of Deuteronomy as following the form of a neo-Assyrian treaty of the type made famous by Esarhaddon in the 7th century. The issue here is the evidence one (approx. 1300 BC) or the other (approx. 700 BC) would have on the dating of the book.

[xvii] Redd, Scott. “Deuteronomy.” A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the Old Testament: The Gospel Promised, 2016.

[xviii] Many scholars believe that Numbers was created as a kind of historical and theological bridge between the priestly writings (i.e. Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus) and the books of the Deuteronomic History (Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings).

[xix] How Jeremiah leans on Deuteronomy – Reformation 21

[xx] Deuteronomy in Jeremiah – Sabbath School (adventech.io)

[xxi] Levinson, Bernard M. “Goethes Analysis of Exodus 34 and Its Influence on Wellhausen: The Pfropfung of the Documentary Hypothesis.” Zeitschrift Für Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 114, no. 2 (2002). doi:10.1515/ZATW.2002.011.

[xxii] Revelation and Authority: Sinai in Jewish Scripture and Tradition (sample chapter) | Benjamin Sommer – Academia.edu

[xxiii] It is thought by some that Dt 12-26 is the not original content of the Moses scroll, but later redactions by Priests. However, the analysis of the Documentary Hypothesis claims these chapters as from “D”, not “P”. This is quite likely, as, as noted above, Dt 12-26 is an elaboration on each of the “Ten Words” (in the order of Dt 5), which serves as the bedrock of the Law.