Introduction

Most of us read the Bible as at most a narrative of the history of God’s people, culminated by some revolutionary stuff in the New Testament. And, it certainly, on one level, is that. But few of us read the Bible carefully enough or deeply enough to see its deeper construction as an intricate weaving of individual, but connected, narratives that all create a larger meta-narrative.

In this piece, we’ll look at some of these connections, some of the Bible’s repeated narratives that act to drive home its basic premise – the failure of humanity to live in accordance with the will of God. In doing so what we hope to reveal is the immense beauty and genius and grandeur of the Biblical narrative that may provide you a different way to interpret what you may read every day there – to see in the Biblical narrative something quite new to you that makes it so much more impactful.

A tall order, that we aspire to fulfill.

Background

If I fail in this objective, it is in no way a reflection on my inspiration for providing it. I recently took a course from Bibleproject.com entitled “Introduction to the Hebrew Bible”, an innocuous enough title, given by instructor Tim Mackie. Its purpose is to reveal some of the interconnection mechanisms and common themes between Biblical narratives that act to integrate them into a whole that might otherwise be missed by the casual reader[i]. And it surely accomplished its purpose in my case.

Impediments to Seeing the Story

Most Christians are taught Christian narrative and doctrine by somebody else. That is, they don’t independently read and research the text but rather listen to those whom they trust to tell them what the narrative means and which doctrines to profess.

This is fine so long as the one teaching you is reliable, trustworthy, and knowledgeable of the deep meaning of the texts in their original languages so that he can draw out those features of it hidden by English translations. It would be a tremendous bonus if that same honest, trustworthy teacher could see and teach you the linkages between the mosaic’s narrative pieces that act to place them within the overall picture – the meta-narrative.

This is generally not the case. Most of us are taught by those who at best parse the individual narratives in their original language and so can bring out some of the meanings that are obscured to us in relying on English translations.

But, if they don’t see the almost organic interconnections between stories that link them together into a grander story, they will fail to see the absolute beauty that has been produced by the Hebrew Bible’s authors that have been enlisted by God to tell His story.

Sadly, very few people have spent the time necessary with the text of the Hebrew Bible to understand this higher narrative and how it is crafted from its intricately positioned and connected mosaic pieces/narratives[ii].

The Mechanics of Narrative Interconnection

So if some verses of the Bible are “interconnected” with one another, how?

The principal mechanism we find is the repetition of words or phrases. The somewhat knowledgeable reader of the Bible will recognize that repetition of words or phrases is the hallmark of another principal form of Hebrew literature – Hebrew poetry. Hebrew poetry features the repetition (or perhaps “restatement”) of a statement in collections of two or more consecutive statements to emphasize the point they are making. A simple example may be helpful: Psalms 56:1-2

[56:1] Be gracious to me, O God, for man tramples on me;

all day long an attacker oppresses me;

[2] my enemies trample on me all day long,

for many attack me proudly.

With examples like this, it’s hard to miss the author’s point. But this use of repetition only links local, proximate statements to emphasize the primary point or statement. Consequently, they’re very easy to see.

Repetition of words or phrases across widely separated passages take more effort to see. Their purpose is to tip us off that a point is being emphasized via reprise that we may have first seen chapters previously.

We’re not talking here about literal repetition, as, for example, when the text of a story in Kings is lifted (and embellished) into Chronicles, or text lifted from Micah 4 and inserted in Isaiah 2. No, we’re referring to parallel stories – different stories involving different characters that share common elements signaled by common words or phrases.

To see these linkages one has to have a fairly good knowledge of the Tanakh. If you’re a beginner, it will take some time in reading and re-reading portions of it before you have accumulated sufficient memory of its words and stories that when you encounter a word or phrase, you realize that you’ve read it before. You stop and exclaim: “Hey wait a minute. I read something just like that last week. What was it I was reading?”, and then go find it.

This linking is quite fascinating. Imagine being a Hebrew author of one of the scrolls contained in the Tanakh[iii]. You’re telling a story (within a “literary unit”) that you know is deeply related to a story that you or another scribe has previously related in your own or another scroll (another “literary unit”).

How do you convey to your reader this connection – this “coordination”? Their answer was to pick up words, phrases, or narrative themes used in the telling of the earlier narrative within their own, perhaps projecting roles or meanings onto the people and circumstances in their narrative imported from the earlier one. In literary terminology, such linkages are called “coordination”. (We’ll look at a few examples of this, below.)

In this way, we can find what Tim Mackie calls “hyperlinks” embedded within these fifth-fourth century BC texts identical in functionality to web hyperlinks that support an online reader to jump easily from his current page to another with which it is linked[iv],[v].

Some Mosaic Pieces and Their Connection to Other Pieces

Genesis 3 And Genesis 6

Beginning in Genesis 1 we have the recitation of God creating, and consistently declaring it “good”. Since no one else existed at that time, no one else’s moral standards or concept of what was “good” was involved. God was (and is) the sole agent in Whom the concept of “good” is established. Something is good, by definition, if the author of the concept said it is.

However, fast forward to the Garden and the infamous dialogue between the snake and Eve. Suddenly, Eve makes a judgment of the “good”ness of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, causing her to “desire” it.

Eve takes on the role, up to this point the exclusive role of God, of an arbiter of “good”. Notice that she didn’t “know” the Tree to be “good” since she had not yet partaken of its fruit. But, she nevertheless judged that it was good, defying the instruction of her Creator and assuming His role. (This sin, we should notice, occurs before actually eating any fruit of the Tree.) What better description exists of our modern society?

So she “takes” its fruit, and sets up another dichotomy. God had been consistently giving in the establishment of His Creation and the idyllic Garden for the Man and the Woman. But now, in a kind of moral cataclysm, the Woman “take”s, rather than simply receiving from God.

Later on, we will continue to see the dichotomy between God’s giving/blessing and man’s taking played out in innumerable narratives (e.g. Abraham and Sarah taking from Hagar and Ishmael, Jacob taking from Esau, Joseph’s brothers taking from him, etc.). As well, we’ll see the stark contrast between man’s behavior and God’s judgment of it. Suddenly, everything is not “good”. It is quite bad.

This transition is cast in stark relief: We start with an idealized Garden, move on to the Garden debacle, and from there on to the narrative of Genesis 6 involving the “sons of God” and God’s reaction to their ungodlike behaviors.

Here we have several “hyperlinks” between the Gen 1, 3 and 6 stories:

| Genesis 1 | Genesis 3 | Genesis 6 |

| God sees that it was good | The woman “sees” the Tree is “good” | The sons of God see that the daughters of humanity are good. |

| Eve “takes” the fruit | The sons of God “take” the daughters of humanity for wives | |

| God bids them “multiply” and fill the land | Evil multiplies in the land. The land is filled with violence. |

The reader of Genesis 1-6 almost can’t help but be struck by the obvious failures of humanity signaled by keywords and phrases throughout these chapters that contrast with their usage in Genesis 1. The narratives, taken together, have a higher meaning and act to begin framing a higher narrative than any of them individually. These are the interlinked mosaic pieces we’re looking for.

You Shall Bruise/Crush/Strike (7779. שׁוּף šûp̱) His Heel

In Genesis 3 the sin of the two humans is revealed to God (v8-13). God then pronounces His judgment on the Garden’s inhabitants, starting with the snake (v14-15):

[14] The LORD God said to the serpent,

“Because you have done this,

cursed are you above all livestock

and above all beasts of the field;

on your belly you shall go,

and dust you shall eat

all the days of your life.

[15] I will put enmity between you and the woman,

and between your offspring and her offspring;

he shall bruise your head,

and you shall bruise his heel.”

What exactly is going on here? Verse 15 tells us God will put enmity/acrimony/hostility/animosity between the serpent and the woman (apparently as the Mother of all humanity).

Then it says: “between your offspring and her offspring”. Wait a minute. The Serpent is going to have offspring? “Snake-beings”, or “snake-people”? Apparently. The message is that they are going to be hostile to Eve’s offspring; that is, all of God’s humanity.

The “he” in v15b is Eve’s offspring – humanity, or One of its members. We/He are going to bruise/crush/strike or otherwise do damage to the Serpent. This is a recurrent theme repeated throughout the Bible. See, for example,

- 1 Samuel 17: David strikes (5221. נָכָה nāḵāh: ) Goliath’s head

- Habakkuk 3:13: In the new exodus, Yahweh will crush the head of the future “Pharaoh”

- Malachi 4:3 – the righteous “trample the wicked under your feet”

- Psalm 68:21: In the new exodus, Yahweh will deliver his people from the region of “snake” (Aramaic: Bashan), and “crush the head” of his enemies.

- Psalm 110:1, 6 The royal-priest of Jerusalem will strike the head of all rebel powers, until all of God’s enemies become his footstool…(6) He will judge the nations, heaping up the dead and crushing the heads of the whole earth.

And what will the Serpent do to us/Him? Bruise/strike his heel. So, the image being painted here is of the human-person stomping down at the head of the snake, but the snake instinctively striking back at the incoming foot/heel of his attacker.

Where else in the Tanakh do we read about a heel? There are three other uses of the word in the Tanakh but only one in which a person takes some action on another’s heel, as a hyperlink to our Genesis 3 verse.

In Genesis 25 we learn of Abraham and Sarah’s deaths, and the genealogy of Abraham’s sons Ishmael and Isaac — specifically Esau and Jacob. Isaac’s wife Rebekah gives birth to twins (v24-26). Esau is the firstborn of the two, but Jacob[vi] has a grasp on his brother’s heel as he is born. Why? Why is this detail purposely a part of the narrative of Jacob, who is to become the nation of Israel?

First of all, we should acknowledge that Genesis 3’s “bruise/strike/crush” is not the same word as Genesis 25’s “hold/grasp” (270. אָחַז ‘aḥaz). But it is unmistakable that the Bible is drawing our attention by analogy to the two situations of one taking some action against another’s heel. If we trace through that with Jacob, what do we find?

In Gen 3, it is the snake who strikes at Eve’s offspring’s heel. In Gen 25, it is Jacob who grasps Esau’s heel. Jacob is here cast in the role of a “snake-person”! This is apparently because, as the book of Genesis unfolds, Jacob deceives (an evil, snake-like act) his father into giving him the blessing intended for Esau by impersonating him (with, we should note, his mother’s encouragement). Just to make things even more complicated, we should also note that God prophesied to Sarah that this would happen: that “the older will serve the younger”, i.e. that Jacob (literally, the “grabber”) would receive this inheritance.

Interestingly, Jacob as the father of the twelve sons who will become the nation of Israel then himself is deceived by his sons as they create the story of the son Joseph being slain by wild animals. It’s as if the natural, moral compass of Eve’s offspring inexorably becomes the moral compass of the snake’s offspring. The two peoples become indistinguishable. And, this is a major foundational theme repeated throughout the Old Testament and a huge piece of the meta-narrative.

You can absolutely lose yourself in following all of these linkages between narrative literary units throughout Genesis, in particular, but throughout the Tanakh in general. Track, for example, the image of the blood of the lamb/goat between the deception involving Joseph’s coat (Gen 37:29-35) and the tenth plague narrative (Ex 12:23-28). Who was the sacrificial lamb in the Joseph story? What was the purpose of the sacrificed lambs in the tenth plague? God seems to be weaving His story of the redemption of snake-people deep into the fabric of His Tanakh. There are so many deeply revealing plots and sub-plots embedded here, most of which are interlinked to one another, with each revealing yet another dimension of what turns out to be a primary story[vii].

Jesus Fulfills the Tanakh

In Matthew, we read of Jesus visiting John at the Jordan. And there God’s Spirit hovers over the waters as He had previously “gathered them together” in one place in Genesis 1:9, and He declares “This is my son. In Him I am well pleased.” Here Jesus emerges from the waters and God is “well pleased”. In Gen 1:9 God had revealed the land from the seas and declared it “good”. And Jesus’ ancestors, the Israelites, had emerged from the waters of their redemption. And He, like they, is immediately cast into the “wilderness” (the desert) and tested by the Tester, just as the Israelites had been tested in their desert following their release from slavery.

What happened when Jesus’ ancestors were tested? They failed. The molten calf, the rejection of Moses as God’s appointed leader, the complaining. This was the product of the Exodus generation’s wilderness experience.

What happened when their seed, Jesus, was tested in the wilderness? He was victorious over the Tester’s trials.

But Jesus, the human, wasn’t done being tested when He dispatched the Tester in the wilderness. His ultimate testing as the Son of Man came in Gethsemane. Here He says (Matthew 26:39):

[39] And going a little farther he fell on his face and prayed, saying, “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as you will.”

The word “will” here (2309. θέλω thélō; fut. thelḗsō.) means “desire”. And, we’re immediately reminded of Eve’s compulsion in the Garden and her “desire” for the Tree – that it was “desirable”. This is so fascinating.

Eve’s desire for the Tree led to death, both physical and, we can surmise, spiritual in that it resulted in Adam and Eve’s removal from God’s presence. In contrast, Jesus sacrificed His desire (Mt. 26:39), deferring instead to the desire of the Father. And, it led to His physical death, but His spiritual glorification and eternal life in the Father.

We can look at the hundreds of interconnected pieces of the Biblical mosaic for a very long time and not find two more revealing of its grand meta-narrative. Humanity’s innate “desire” from the beginning was to reject God as its Shepherd and Father. Christ arrives and seeks nothing but what God desires. In between these two events are the thousands of mini-stories documenting humanity’s persistent striving to ignore God and gain for themselves – to “take”, if you will.

Then Christ comes and in total obedience to His Father gives all He has, on our behalf, to enable us to break free from our deadly self-absorbed obsession. This is what the Bible means when Jesus says He came to fulfill (Mt 5:17-19) what the Law was given to produce in people by defeating their sin and eternal death (1 Cor 15:57).

Conclusion

The Hebrew Bible is an extremely intricate tapestry or mosaic of stories interlinked with each other. We have barely scratched the surface here. They tend to repeat, and so reinforce, some basic themes – man’s penchant for deception and deceit, man’s penchant for the opposite of what God prescribes for the good of man, God’s immanence in history, despite man’s rejection of Him, to give success to those He chooses to implement His plan.

And its unrelenting portrayal of people, whether God’s people or those manifesting as “snake-people” disobedient to God’s will, cannot help but focus our attention on the ultimate resolution of man’s separation from his God – Christ the redeemer.

He was faithful; He was resolute; He was undefiled, and He was selfless. But most importantly, He was preeminently victorious through his physical death and resurrection over Man’s sin and death.

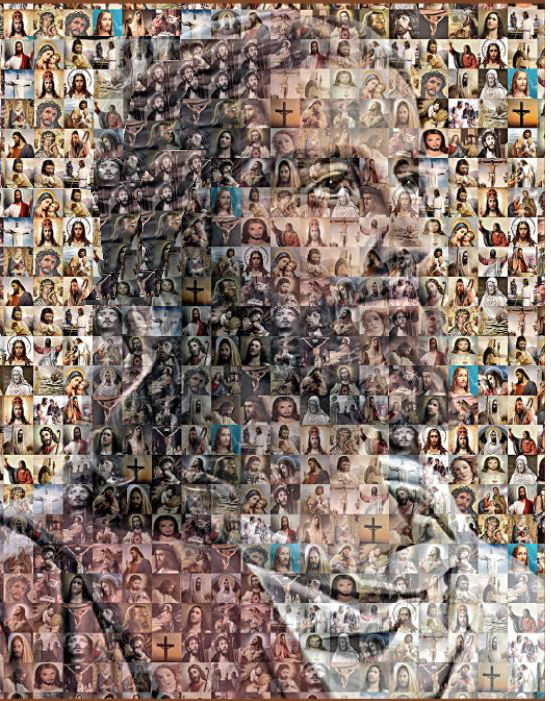

Christ is portrayed as displaying the opposite of the traits of humanity seen throughout the Hebrew Bible, though He was totally human. This is why He is the culmination, the overarching image of the mosaic of the Hebrew Bible as its resolution. It is His image that resolves all of the smaller images into an integrated, redeemed, whole.

[i] The name Jacob — 3290. יַעֲקׂב ya`aqōḇ — means something like “he seizes”

[ii] The website AlephBeta.org has a wonderful series of animated teachings on the Tanakh that explore these linked narratives that I highly recommend. (For example, check out the series identified as “Goats and Coats”.) Particularly for those of us who don’t know and can’t read the underlying Hebrew of the Tanakh, instructional (and entertaining) aids such as those at this site offer a wonderful way to see these texts more deeply, more organically than we are otherwise able.

[iii] If you have a spare half-hour I would encourage you to listen to this session of the course in which Mackie explains and gives examples of the mosaic of the Hebrew Bible that forms the foundation of what was for me an entirely new way to read it.

[iv] Perhaps some people have developed a comprehensive knowledge of the Hebrew Bible’s interrelated narratives and I’m just not aware of them – academic Rabbi’s, for example. But if I’m not aware of them, it’s likely the average Christian isn’t aware of them either. Which is the problem.

[v] The word “Tanakh” is from the acronym formed by the three consonants identifying the three major subdivisions of the Hebrew Bible: T = Torah; N = nevi ‘im (Prophets); and K = Ketuvim, or Writings (e.g. Psalms, Proverbs, Job, etc.)

[vi] Others have referred to this phenomenon as “intertextuality”.

[vii] The BibleProject.com course also points out that these links are used to connect scriptures across books or even genres within the Tanakh; for example, linking “Writings” (Ruth) to Torah portions (e.g. 1 Kings) or other Writings (Proverbs). And, it shows that these major subdivisions (Torah, Writings and Prophets) are linked together via textual links. Certainly, having had these links explained to you gives you an entirely new respect for the genius (or inspiration, if you will) of the authors of these texts, given that they were finally constructed some 2500 years ago when most all people simply raised crops or livestock, or possibly had a trade. We’re not used to thinking of them as literary giants, which the authors/editors of the Tanakh most assuredly were.