Introduction

When did “Judaism” begin to be widely practiced (i.e. widespread adherence to what we today recognize as the rules and calendar of the Pentateuch)? Irrespective of when the individual books of the Pentateuch were written, when did the majority of Judeans begin to live them out? The answer is quite shocking.

And, aside from completely dismantling the traditional understanding of Israel’s history by both Jews and Christians, what implications does this dating (as well as the dating for the Hebrew Bible itself) have for how we should think about Judaism’s development, and Christianity’s explosion in the first century?

The Origins of Judaism

What do we mean by the term “Judaism”? Yonatan Adler in his studies of the subject uses the following meaning:

‘“Judaism” will serve as the technical term for what I have described here: the Jewish way of life characterized by conformity to the rules and regulations of the Torah…characterizing the Jews as a people.’

We can assume that some specific practices (e.g. circumcision, Sabbath observance, food restrictions that later were referred to in the Pentateuch) were sometimes practiced at some points in Israel’s history by some of its people or priests. But there is no evidence that these practices were legislated nor promulgated as a legal corpus to the people. So far as we know they were simply a part of the cultural heritage of at least some Israelites that passed them down from generation to generation orally and by example.

How does one go about establishing when Judaism actually began to be practiced by Jews as a people?

Adler (an archaeologist, not a biblical scholar) has written a masterful book[i] analyzing various types of historical “data” – Biblical and extra-biblical texts, zooarchaeology finds, and recovered coins, religious relics, and synagogues to answer this question. It’s important to understand that the question is not when the Jewish “religion” was created. The question is: When did the Jewish/Israelite people actually begin following it as a cultural mandate, based on textual and material evidence? Or, as Adler put it in a predecessor paper[ii], when do we first see evidence of following Jewish Halakha (law-keeping) among the population at large? Yes, they had temples, and yes those temples were operated by the temple cult. But how did that cult influence the daily practices of the common Jew, if at all?

Perhaps another way to clarify the question is: “How long before the Apostle Paul identified ‘works of the Law’ to his Jewish (and Gentile) brothers were the Jews actually engaged in these “works”, by which is meant the rituals and practices spelled out in the Levitical Torah, as a matter of daily routine, as a people?

Adler’s methodology for determining the answer is to review all of the above-mentioned sources of “data” starting in the 1st century AD, and moving progressively backward in time until he can find no more “data” attesting to Judaic practices in the Southern Levant. His idea is simple: If Judaism was being practiced, there should be archaeological and/or literary evidence of the population’s adherence to Mosaic laws. On the other hand, if no such evidence can be found for a given time period, the only thing we can conclude, Adler points out, is that we don’t have the requisite data to “prove” the practice of Judaism at that time: “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

And, interestingly, Adler, in questioning the advent of Torah-based Judaism, does so for the identity group he identifies as “Judeans”, a term he applies to those who actually practiced Torah observance as a society. And, the way he sees it, there is no such thing as a “Jew” until this identity of “Judean” defines their society.

I don’t particularly agree with this distinction. Surely, in the exilic and post-exilic years (say 6th-4th century BC), the residents of Judah were, predominantly ethnically, Jews. Of course, as Adler asserts, they were not yet “Torah observant” as a society. But at the very least geographically, they were residents of Judah – Jews.

Adler’s Data

Zooarchaeological Data

In this category, Adler concentrated on evidence of pig bones and catfish remains in the diet of people in the southern Levant, in contradiction of the Pentateuch’s dietary restrictions (Lev 11, Deut 14:3-21). This strategy is less conclusive than one might think as a result of many neighboring cultures (e.g. Egyptians) also avoiding pigs in their diet.[i]

However, the rarity of such remains in 1st century contexts demonstrates that at that time, kashrut (Jewish dietary laws) seems to have been in widespread application. Adler particularly provides the evidence from three “fauna assemblages” uncovered in the excavations of Jerusalem’s Givati parking lot excavation (see photo) that demonstrate an incidence of pig bones of only 6% in the first century.)

Such is not the case in the Persian period in which catfish remains are plentiful in archeological finds of that period in Judah. Pig bones are also somewhat more prevalent in Judaic contexts in the Persian period.

Conclusion? Torah adherence had not become a cultural mandate in the Persian period but seemingly had by the time of the Greeks and Hasmoneans.

Inscriptional Portrayals (“Figural Art”)

Adler reports that Jewish coins excavated from 1st century BC to 1st century AD contexts portray only geometric and, occasionally, Menorah-themed depictions. No humans and no animals.

Such is not the case in the Persian period (539-332 BC), when leaders are commonly portrayed on coins. Of course, this was a violation of Moses’ first(/second) commandment (Ex 20:4):

4 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

This is perhaps the most compelling evidence for the absence of Judaism in Persian period Judea (Yehuda). Additionally, Adler finds passages in the Hebrew Bible implicitly endorsing the representation of such figures, as in the description of the twelve bulls supporting the Temple’s “bronze sea” (1 Kg 7:25). If the Bible itself endorses, if only indirectly, animal images being crafted (and publicly displayed), then clearly, Torah observance was not then in effect.

Ritual Purity

Adler notes that 1st century Jerusalem is full of examples of Mikvahs (ritual baths) and chalk liquid vessels (declared to be pure). As we track back in time, however, these artifacts diminish and eventually (by the early Persian period) disappear from Judean contexts.

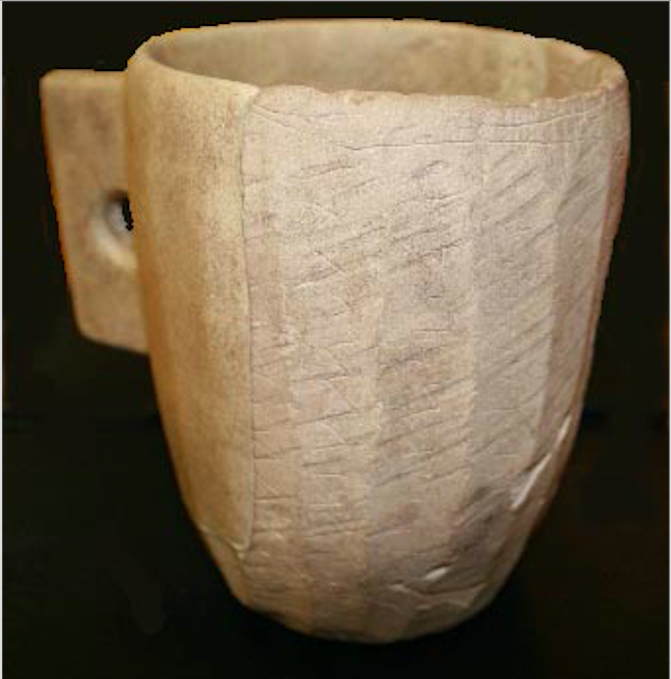

The Torah as we have it today, however, provides clear guidance on ritual purity for the average Judean. While stone vessels (see adjacent cup photo of an example our dig recovered on Mt. Zion) are not explicitly invoked in the Torah, their widespread adoption by the 1st century AD indicates their adoption by cultural Judaism as supporting ritual purity.

The use of “living water” for ritual cleansing, however, to remediate ritual impurity is better attested. For example, Lev 15:13 and Num 19:17 call out the use of “living/(‘fresh’) water” which late 2nd Temple mikvahs used exclusively. 1st-century mikvahs typically were supplied by collected rain water, a type of “living” water.

Tefillin and Mezuzot

Deuteronomy 6:4-9 contains the instructions:

4 “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one. 5 You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. 6 And these words that I command you today shall be on your heart. 7 You shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise. 8 You shall bind them as a sign on your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. 9 You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.

Assuming the Halakha was being widely followed, Adler reasoned, we should be able to find evidence of the devices that contained tiny scrolls containing these verses that were both worn (Tefillin – small leather containers. See above left photo), as well as affixed to the faithful Jew’s doorpost (Mezuzot [singular Mezuzah] – typically small wooden containers of the tiny scrolls, affixed to a home’s doorpost. (See right photo above.)

Perhaps by now unsurprisingly, Adler found ample remains of Tefillin in 1st century AD contexts (interestingly, from material found in caves in the Judean Desert, many still containing small tefillin “slips” — very thin leather strips on which appear key Torah verses). Similarly, several examples of Mezuzot have been recovered from Qumran’s Cave 4, although experts dispute whether they represent Mezuzot or Tefillin slips. Adler notes that both Josephus and Philo also describe these practices by the Jews of their day (1st century).

Prior to the 1st century AD Adler notes some speculative textual evidence for the practice of Tefillin and Mezuzot including a reference in the 2nd century BC Letter of Aristeas and the Nash Papyrus (speculated to itself be a Tefillin/Mezuzot “slip”). However, no physical evidence has been uncovered that would conclusively date these practices to earlier than the 1st century AD.

Miscellaneous Practices

This is a kind of “catch-all” category of Judaic practices Adler employed that would attest to the presence of an active Jewish community that was observant of several rituals required in the Mosaic Law. They are:

- Circumcision

- Sabbath Prohibitions

- Passover sacrifice and the Festival of Unleavened Bread

- Fasting on the Day of Atonement

- Sukkot ritual observance: a) Residing in Booths, and b) taking the “four species”

- A continually lit Menorah in the Temple

After surveying a large quantity of textual evidence for each of these rituals, Adler concludes:

“All these elements of first-century-CE Judaism are attested in the first century BCE, and some also in the second-century BCE, but none are clearly attested to prior to this.”

He goes on to conclude:

“This conclusion should cause us to reconsider the quite common notion within scholarship since the time of Wellhausen that at least some of the observances analyzed here had become widespread beginning already with the Babylonian exile and the early days of the so-called Return to Zion. It is certainly true that all the practices examined in the present chapter appear in portions of the Pentateuch commonly identified as ‘Priestly’ sources (P and H), and in several cases they appear exclusively in such passages. But while most scholars date the so-called Priestly material to the ‘exilic’ or ‘postexilic’ periods, we must be exceeding careful not to confuse the date assigned to a document’s composition with the time when it came to be widely accepted as authoritative or legally binding among the masses of ordinary Judeans.” (Emphasis mine.)

Synagogues

At first blush, this category of investigation seems quite odd. Certainly, the people were not commanded in the Mosaic Law to attend a Synagogue. The Hebrew Bible knows nothing, in fact, of such things, and does not contain the word.

However, Adler’s interest in examining the rise of the Synagogue in Jewish life in the 1st century is to identify it as the primary mechanism of spreading the message of the Torah to the Jews at large. And not just in Judea but throughout the world of Jewish communities.

He notes that Philo, the Gospel books and Acts, and Josephus all paint a coherent picture of the place in Jewish community and their law-reading role of synagogues in first-century Palestine. If you’re a tourist, you can walk through the physical remains of scores of first-century synagogues from the Galilee to Masada, and indeed throughout the entire Middle East wherever Jews had settled (Magdal synagogue pictured). In Paul’s epistles and the book of Acts you can read of his regular visits to synagogues throughout the Ancient Near East (ANE). While Adler notes that there are a couple of references from late 2nd century/early 1st century (BC) in material that could conceivably describe community synagogues, this is by no means assured.

What we do know is that synagogues in the 1st century were the Jew’s internet (or perhaps lecture hall or library) – his source of information guiding he and his family in how to live, based on the emergent Torah – the “Law of Moses”. Each Sabbath he could hear a portion of the Torah read and taught, along with portions of the Prophets and other Tanakh material from its then-nearly complete canon.

Origins of Judaism Reappraised

In this chapter of his book, Adler presents his speculations as to when the Torah’s Halakha would have begun to be seen as authoritative and so most likely to have begun to be practiced by Judeans.

One potential Persian period triggering event was a purported Persian governance policy that each of its conquered nations had to be governed by their own national laws[iii], causing the Torah laws to be written down and, in accordance with the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, promoted as what Judeans should be doing. He then surveys the textual and material data for three Judean communities known from the Persian period: a) Judea itself, b) the community of Elephantine in upper Egypt, and c) Babylon. From the available data, he finds no evidence that the Torah was being followed (and much evidence that it was not), and no evidence that Judeans at these locations knew anything of the Pentateuch as we have it today.

Adler dismisses this scenario due to a lack of reliable evidence of the existence of such a Persian policy of governance, and his assessment that the Ezra/Nehemiah narrative does not represent history[iv], at least for which there is any corroborating evidence. He sees those books as written much later than their post-exilic setting – perhaps the 3rd or 2nd centuries BC. As such, possible corroboration for this governance mandate, as presented in Ezra 7:25, is suspect:

25 “And you, Ezra, according to the wisdom of your God that is in your hand, appoint magistrates and judges who may judge all the people in the province Beyond the River, all such as know the laws of your God. And those who do not know them, you shall teach.

Apparently, what’s going on here (at the very least) is the promulgation of a marketing campaign to raise Judeans’ awareness that what they should be doing, as faithful Jews, is following this as-yet obscured Mosaic Torah centuries after their return from Babylon.

It seems that the book of Nehemiah agrees that the Mosaic Torah was not (at the date of its narrative or perhaps even at the date of its writing) being followed by the majority of Judeans as he complains in Neh 13:15-18:

15 In those days I saw in Judah people treading winepresses on the Sabbath, and bringing in heaps of grain and loading them on donkeys, and also wine, grapes, figs, and all kinds of loads, which they brought into Jerusalem on the Sabbath day. And I warned them on the day when they sold food. 16 Tyrians also, who lived in the city, brought in fish and all kinds of goods and sold them on the Sabbath to the people of Judah, in Jerusalem itself! 17 Then I confronted the nobles of Judah and said to them, “What is this evil thing that you are doing, profaning the Sabbath day? 18 Did not your fathers act in this way, and did not our God bring all this disaster on us and on this city? Now you are bringing more wrath on Israel by profaning the Sabbath.”

Apparently, then, at the time of writing of Ezra/Nehemiah (3rd-2nd century BC – the Hellenistic period), following something known as the “law of Moses” (“torat Moshe”) was, if followed at all, something only adopted by a tiny minority of Judeans. But at that time, it was seen by the priests of the land (of which Ezra was preeminent) as a solution to their endemic apostasy and governance problems, particularly as a newly-freed nation under the Hasmoneans in the 2nd century.

What Caused the Writing of the Mosaic Law? And When Did That Happen?

Beginning with what we can be fairly certain of, there was no societal following of a Mosaic Law, as we know it from today’s Pentateuch, for the entirety of Jewish/Israelite history down to at least the 2nd century BC (perhaps a bit longer). This is Adler’s fundamental conclusion based on all of the evidence he has examined. Judaism as Torah-following was unknown for the first perhaps twelve centuries of Israel’s existence as a defined people group.

In acknowledging this fact, we are not disclaiming the passed-down narratives of the history of the Hebrews – their salvation from Egypt, their penance during their 40-year wanderings in the wilderness, and God’s instructions given them through Moses at Moab. The only thing we can say is that if Moses did, in fact, write down a set of instructions (Torah) describing how they were to live in the land God brought them to[v], the majority of the people either didn’t know what those instructions were or simply didn’t care. To the extent they were known at all, it seems to have been only by a tiny elite of temple scribes and occasionally (e.g. Josiah) a king.

There is no possible way to trace the penetration of the so-called Law of Moses into the pre-exilic nation of Israel. In the Bible’s description of these periods, we have virtually no mentions of adherence to any of the Mosaic “laws”, and certainly not by the people at large. Of course, we have the major and minor prophets both railing against the apostasy of their countrymen covering a historical narrative span of at least 200 years (but probably longer). First-Isaiah may well date to the 8th century BC, pre-Assyrian exile, while Nehemiah, as we’ve seen, likely dates to the 3rd to 2nd century BC – a span of 500-600 years). The prophets, it seems to me, were in the class of those “in-the-know” concerning whatever the “Law of Moses” was known to be in their day, since it would have been the basis of their criticism (Jer 8:8).

The History of “The Law”

So, what was going on with the Israelites between these two historical markers (i.e. pre-exile to 3rd-2nd century)?

Well, for one, nobody (or only a tiny, unremarked-upon minority) was following anything resembling the Mosaic Torah (either the Shapira Scroll version, or the canonical version). Yes, the first and second temples were in operation (except during the 70-year demise of the first temple) doing their sacrifice and offering thing.

It is perhaps easy to see that the characters in the Judges had no idea of the content nor the existence of the Law of Moses. It’s not mentioned. Beginning with David, it is also quite easy to see that he and his surrounding culture, though they would have Solomon’s Temple, similarly had no compelling awareness of a Torah. David is reported to mention a “Law of Moses” (1 Kg 2:3), as is King Jehosaphat (2 Chr 17:9). They knew of “something” from Israel’s past – some ancient instruction. But we have no evidence that the people knew anything about it, never mind ritually following it.

Fast-forward a few centuries and we have the infamous story of King Josiah and the “discovery” of Moses’ scroll in the temple by Hilkiah. How should we interpret this purported 8th-century event in 2 Kings 22:8? Apparently, the authors of 2 Kings (perhaps writing in the 6th century BC) knew something about a Mosaic Law/scroll; just not a Pentateuch as we have it today (as I have argued here).

But the takeaway for me is that for all of the Tanakh (Genesis-Malachi/Chronicles), we have no textual evidence that the Mosaic Law was being followed by the subjects of its narratives.

Adler’s point throughout his book is that there were “fringe groups” that were observant of what they understood to be the “Law of Moses”. What that law consisted of compared to our canonical Pentateuch is not knowable today, at least not conclusively.

Adler provides an important historical analysis of the concept of “law” in various ANE civilizations in antiquity. In it, he makes the following points:

- Very early on (i.e. the Bronze Age), civilizations did not have prescriptive written national laws. They were governed by their Kings whose job it was to adjudicate disputes and dispense justice based on their pedigree as the Sovereign. In many cases, these Kings were thought to have divine origins, and so were trusted to act in concert with the local/national deity’s will.

- Beginning with the Archaic Period of Greece (7th century BC), polities in the ANE began committing their laws to writing. Such written ‘nomos’ was in Greek culture considered a hallmark of civilization. This was also a period of extensive Greek colonization of the ANE nations. Their cultural influence on their new colonies was immense.

- We begin finding textual references to Judah’s “law” in 1 and 2 Maccabees (attributed to the late 2nd century BC – the Hasmonean period). After reviewing Judah’s history of control by the Ptolemais and Seleucids, and their resulting rebellion against the 2nd century reign of Antiochus by the Hasmoneans, Adler presents his conjecture that it was the now-independent Hasmoneans who sought to bond Judeans together through the mechanism of a set of authoritative national laws. The Greek standard of national written law established the environment where these were culturally necessary, in addition to whatever shared cultural binding effect they would exert on the population. They also introduced the concept that “Judeans” (Jews) were no longer purely an ethnic category, but through the promulgation of their law could assimilate other groups willing to adhere to that law, leading to them becoming full-fledged Jews. We have historical records of Judah actually assimilating Samaria, Idumea, and Iturea (per Josephus and Strabo). He also notes that these Hasmoneans didn’t claim these were new laws but simply the reintroduction of ancient, God-ordained laws that had been abandoned by their (apostate) ancestors.

Adler postulates, therefore, that the widespread practice of Judaism began in the late 2nd and 1st centuries BC, as a technique for instilling a national (not ethnic) identity in an enlarged (beyond Judah) population. It seems to me this timing and logic is made more plausible by the fact that the Maccabean Revolt had just defeated the forces of Antiochus with his goal of eradicating any lingering ritual practices of the Jewish people. What better way to assert their new-found independence and cultural identity as the chosen of God than to formally document their origins and Torah?

The main point is that there was a historical memory of a Mosaic “law” given to their ancestors by their God. And some elected to try to adhere to what they knew of it while the majority chose to ignore it. However, it was not the widespread practice of the Jews until beginning in the 2nd century BC and continuing up until the apocalypse of 70 AD.

Before this adoption, the legal practice of the Jews was that represented by the judicial function of their Kings, and later priests, based on whatever cultural memories they shared of their ancestors’ customs and standards.

This all sounds, to me at least, as quite plausible. You had a majority of people who just wanted to go along as they chose (Jdg 21:25…”Everyone did what was right in his own eyes”). You had a minority who believed they should adhere to a higher standard, articulated in antiquity by God.

If you were an Israelite/Judahite, even if your civilization has just been uprooted, destroyed, and banished to a foreign land, and perhaps because of this destruction, who was the God of Israel, and His “laws”, to you? Your fathers, perhaps for several generations, had operated like the surrounding pagans with their sacrifices and their worship of various gods and idols. (Adler notes the presence of large quantities of assumed votive figures perhaps representing different gods extending down through the archeological record into the Persian period.) Should you abandon your cultural pedigree? Why? Because you find yourself exiled to a culture that worships virtually all the same pagan gods you do? To such a person, it might be easy to perceive Israel’s God as the problem, rather than his salvation.

No wonder adherence to the Mosaic Law was such a tough sell.

What Prompted the Adoption of Torah Observance Amongst Judeans?

Between the post-exilic returnee culture of the 6th century and the 1st century BC-to-1st century AD, Israel morphed from essentially an undifferentiated culture from their pagan neighbors, despite the desires of Adler’s minority “fringe groups” and the supposedly YHWH-focused temple cult, to one convinced of and intent on the adoption of what would be called their Torah – ascribed to Moses. Why?

Here we are completely in the realm of speculation. Adler has presented his conjecture that it was the action of the Hasmonean dynasty to promote a single “Jewish” law that also facilitated the inclusion of non-Judean adherents under that law.

The common and still widespread assumption (which I shared until reading Adler’s arguments) was that Torah observance came about as a result of the cultural shock of their Babylonian exile, and the thanksgiving to God for their eventual return to their homeland. Such an experience should have (though we have no literary evidence that it did) created in the common people the conclusion that their pre-exilic lifestyles were an affront to their God and that they were going to have to reform their pattern of living in the future.

Adler seems to disclaim this view based on its lack of verifiable evidence in the Persian period. It’s logical. But we have no evidence to assert that it was reality. And, we have biblical evidence to the contrary in Neh 13:15-18.

We also have the theory of Persian imperial authorization, and the testimony of the book of Ezra, which Adler similarly cannot justify. In addition, we have scattered literary evidence of the idea of common Judaic rituals (e.g. Sabbath-keeping, even some apparent Passover references) from Persian period Judean communities (Judah, Elephantine, Babylon). But that same testimony gives no indication that these were practices authorized by some “law”. Rather, they seem to simply have been practices passed down from earlier generations.

While the Greeks during this period were formalizing governance standards for their polities; the requirement to have written laws that governed their dealings, this Hellenistic influence had not yet (5th-4th century) sufficiently penetrated Persian Judah (Yehuda). For Persian period Judahites, it was good enough that they remembered the traditions of their ancestors and acted to preserve them. This was also true for the practice of adjudicating disputes and crimes.

Whither the Prophets?

Were the prophets a 7th-5th century invention of Judaic scribes? Or were they, rather, real people who had an understanding of a primitive Mosaic Law that the people and their leaders ignored? Because of their prominence in the canonical Tanakh, it seems incongruous that later scribes, in assembling the Hebrew Bible, would feature the admonitions of men so thoroughly condemning of the sins of the people against their God. Why demean God’s people in such withering terms, and feature these criticisms in the books that comprised the stories of Israel’s origins?

It seems there must have been a painful memory of Israel’s earlier apostasy and the Prophets’ condemnation of it. If you were a late second-temple official seeking to implement a prescriptive national law to insulate your people from sinning against their God and equip them to govern themselves, the Prophets (including, of course, Moses) were the perfect people/authorities you would seek to enlist in your enterprise.

And so, they likely were.

Conclusion

For traditionalist Jews and Christians, the idea that there was no operative “Law of Moses” within Judah until the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD is quite the heresy. You know, Moses wrote the Pentateuch, and the people followed it as they agreed at Sinai (Ex 19:8).

The conclusion of scholarship and its supporting literary and material evidence is: “We don’t find that in the data.”

The composition and promulgation of the Hebrew Bible is “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma”. But, we can review the available data and, if not identify precise dates and precise motivations (whether political, theological, or cultural), get closer to the truth than blind acquiescence to the traditional narrative.

And what’s the value in doing so?

Aside from the somewhat abstract value of getting closer to the “truth”, I think it helps us keep our focus on the major things, not the minor things. Even given Adler’s analysis here, it has been (I think) demonstrated that there was a cultural history of Israel that was preserved down to the ultimate promulgation of the Torah. That history was informed by something. The story of Moses and its legend of the scroll at Moab has no historical exemplars. In other words, no other people/civilization claimed such a thing for Israel to emulate. It is historically unique.

So it must have had some kernel of historical basis. Why Israel, and then Judah, ignored it for as long as they did through the worship of idols, ignoring the Sabbath, intermarrying with non-Jews, etc. seems to be due to a lack of responsible leadership, not the absence of a Mosaic law. Their leaders (as we’ve noted) seemed to have known of Moses’ Torah for centuries, yet didn’t feel compelled to promulgate it to their people as authoritative.

Now the elephant in the room is the extent to which our Pentateuch, as the Torah of Judaic faith and practice, and as finally implemented in the 1st century BC-1st century AD, actually reflects the historically remembered “Law of Moses”. I have my doubts.

[i] Adler, Yonatan, “The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal”, The Anchor-Yale Bible Library, Yale University Press, 2022

[ii] Adler, Yonatan, “Toward an “Archaeology of Halakhah::Prospects and Pitfalls of Reading Early Jewish Ritual Law into the Ancient Material Record”, Archaeology and Text, Vol 1, Lehigh University, 2017

[iii] The so-called “Theory of Persian Imperial Authorization”,The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance. Edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2007, 22–38.

[iv] Adler, Yonatan, “When Did Jews Start Observing Torah?”, TheTorah.com

[v] As I have written elsewhere, I thoroughly believe God did in fact give Israel instructions for living in Canaan through Moses. See, for example, “Moses Real Words?”