Introduction

In the 1880’s an antiquities dealer in Jerusalem came into possession of an apparently ancient “scroll” consisting of sixteen strips of leather containing paleo-Hebrew texts. Within a period of five years of their “publication”, the fragments had been declared forgeries by “experts” in Europe, and shortly thereafter, the antiquities dealer, Moses Shapira, committed suicide in a Rotterdam hotel room in 1884.

But what if they were authentic? That’s the question I want to pose and try to answer.

The Story

Teacher, author and Bible scholar Ross K. Nichols has devoted several years to tracking down the Shapira story and the content of these fragments[i], which he dubs in his book of the same name, “The Moses Scroll”[ii]. The story reads like a great historical novel with a tragic ending. I highly recommend Ross’ book (and, BTW, his Youtube channel videos on the subject.)

I’m not interested here in trying to even summarize the scroll’s intriguing story. There are many resources out there from which you can review that fascinating and tragic story (particularly Nichols’ bookii, and a summary article by Fred Reiner[ix] ) . My/our interest is to look at some of the key factors influencing the evaluation of its authenticity and assess the implications if, in fact, it is authentically the scroll of Moses – a kind of proto-Torah.

Those to whom Shapira conveyed these fragments for examination had mixed reactions. Some thought them authentic, but over time those that didn’t seemed to win out resulting in the forgery charge.

A Forgery?

What didn’t those who saw the fragments think was authentic? Well for openers, Shapira had been involved in a transaction with the Prussians of supposed ancient [iii]Moabitic materials, that were later found to be forged. In addition, there was some scholarly pushback on its use of words unknown in the canonical text, and its orthography (spelling, punctuation) and paleography (letter/symbol formation) that appeared to mimic the then-recently discovered Meshe Stele (in addition to using some of the spellings unique to the Stele). So, it was assumed the author/forger had used these features of that Stele as a pattern (a Moabite text, at that), as well as some of its lexicology (words and phrases). (You can read the gist of these arguments in Herman Guthe’s “Fragments of a Leather Manuscript”, translated from German by Ross Nichols.[iv])

Modern scholars[v] have similarly examined the paleography and since it doesn’t match any other paleography from any time period, have used that fact to conclude its inauthenticity.

…Maybe Not

Recently (2021) a scholarly treatment of the material by Idan Dershowitz – “The Valediction of Moses: A Proto-Biblical Book” (or “V”, for short)[vi] was published. An important feature of V is that it answers the many scholarly objections raised by its 19th-century critics through both textual analysis and clear examples of supporting evidence now available to us, but that was unavailable to the first reviewers. Others are also becoming convinced of its authenticity[vii].

Interestingly, it seems a lot of the early reviewers’ outrage at Shapira’s presentation of the scroll was that its texts fundamentally differed from their canonical form, and so we see quite emotional rejections of even the possibility of the scrolls’ authenticity, such as this report of a quote from a reviewer identified as a Professor Schlottmann:[viii]

“How I” [Shapira] “dare to call this forgery the Old Test[ament]? Could I suppose even for a moment that it is older than our unquestionable genuine Ten Commandments?”

We’ll look at those differences below.

The argument was also raised that such fragments couldn’t possibly have survived through the intervening, say, 3,100 years since no ancient Biblical documents of any kind had turned up in those millennia. All we had was the 1000 AD work of the European Masoretes (and some earlier New Testament scrolls).

But then the Qumran discoveries happened in 1947 (and the Nag Hamadi scrolls the year before). And since that event, everyone now expects to find documents in the caves surrounding the Arava on both sides of the Jordan. These fragments were alleged to have been discovered in a cave on the east side of the Dead Sea sometime in the 1870s by local Bedouins.

Our first task in assessing Shapira’s scroll is to see what it says compared to what the portion of the Torah it corresponds to says.

The Setting of the Text

As we’ll see, the text of these scroll fragments mirrors texts found in the canonical Torah, almost exclusively in Deuteronomy, but also a fragment of Numbers. We need to keep in mind that our presupposition will be that these texts are, in fact, Moses’ texts recited to the children of Israel in Moab before they entered the land promised to them and their ancestors. So, the questions we’ll pursue are: If these are Moses’ authentic words to Israel before entering Canaan, where did all the other stuff we find in Deuteronomy, Numbers, Leviticus, and, to a degree, Exodus come from, and what does that mean for us today?

The Text

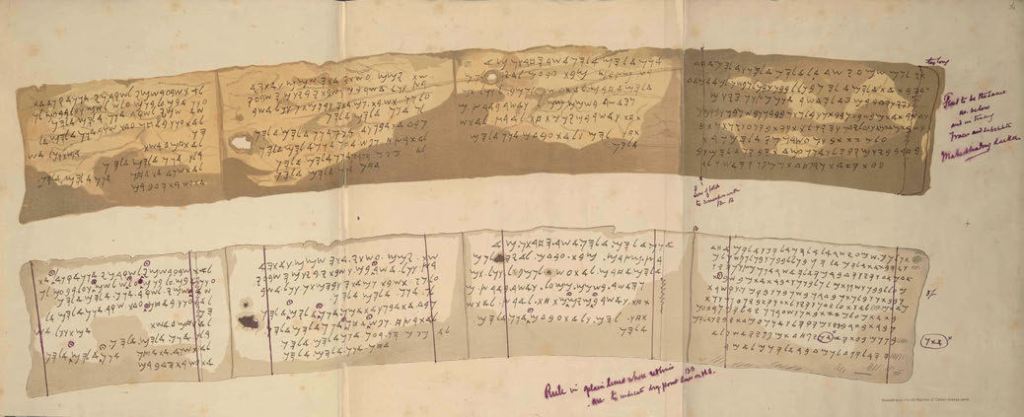

Several scholars examined the scroll fragments in the late 1800s, transcribed the paleo-Hebrew character sequences they found (no vowel symbology or punctuation, other than “interpuncts” [word separators] in the Ten Words section), and then tried to transliterate them accurately into modern Hebrew, a non-trivial task. Shapira, himself, additionally provided an English translation of a portion of the text as did a scholar named Christian David Ginsburg. Ginsburg’s translation is available on the Shapira Scroll Wikipedia page. We’ll use it, below, to compare and contrast the scroll text with the Biblical text.

I have borrowed that Wikipedia page’s table of Ginsburg’s translation and augmented it with both the corresponding Deuteronomy or Numbers texts (ESV), and with Ross Nichols’ translation (with his permission), to make the comparison between scroll and Bible easy (Linked Translation Table).

There are a couple of areas where the corresponding biblical reference for a section of scroll text is a large, multi-verse portion of the Biblical text. Where that is the case, I’ve done my best to dig into the gross reference (e.g. “Numbers 25”) to try to identify the specific biblical verses that best correspond to each individual scroll passage within that broad reference.

I’ve prepared this table as a separate document, which you can open with its link (hopefully in a separate window) and refer to while reviewing the balance of this paper.

Table 1: The Ginsburg and Nichols Translations of the Shapira Scroll

To aid in following the literary structure of this narration comprised of only a linear series of verses, I’ve prepared the following outline of the scroll text to aide you in seeing its structure.

- Introduction and Setting

- Recapitulation of the Travels from Horeb

- To Kadesh-barnea (This is likely our misunderstanding. See the conclusion of “Which Way to Horeb“)

- Judgment Against the Current Generation

- From Kadesh-barnea to Edom – the Horites

- To Moab – Rephaim

- To Ammon

- To Bashan: Og

- To Beth-peor

- Instructions from God

- Make No Idols (this is considered the first of the Ten Words – see the Shapira Decalogue here.)[xiii]

- The Shema – Consider God’s Laws Constantly

- The Ten Words

- Keep the Sabbath

- Honor Father and Mother

- Don’t Kill (the Soul of) Your Brother

- No Adultery

- Don’t Steal

- Don’t Swear by God’s Name to Deceive

- Don’t Lie About Your Brother

- Don’t Desire Your Brother’s Stuff

- Don’t Hate Your Brother

- Encouragement To Enter the Land

- Do All God’s Commandments and You Will Succeed

- Blessings and Curses

- Recite them On Gerizim and Ebal

- Blessings

- Curses

- Postlude

Differences Between Deuteronomy and the Shapira Scrolls

What’s in Deuteronomy that isn’t in the Shapira Scroll?

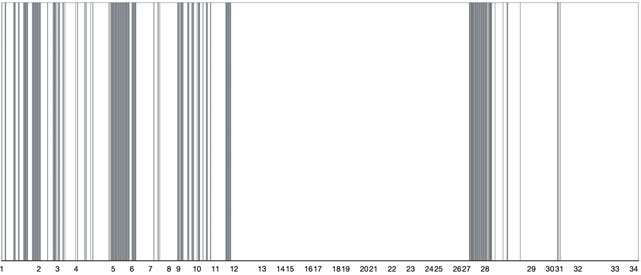

Perhaps the best way to get into this subject is the following graphic (Figure 2) that depicts the portions of canonical Deuteronomy that correspond to the verses of the Shapira Scroll (shaded).

The first impression we’re left with is that there is a huge quantity of Deuteronomy that the scrolls don’t include. By (English) word count, the scrolls contain 13% as many words as Deuteronomy – roughly 3,400 Vs 26,700. About 9,750 of Deuteronomy’s words comprise the “Law Code” (Chapters 12-26) – itself nearly three times the size of the entire “Moses Scroll”.

If we stipulate that Shapira’s scroll was proto-Deuteronomic – a precursor – then we can at least look at the later additions and redactions of its content over time as the rationale for this smaller text growing over time into the larger. Since the scroll appears to be complete in itself[x] – i.e. not missing a beginning, ending, or coherent middle – we should ask: “What would be the point of producing what presents itself as the first-person scroll of Moses, while leaving out vast tracts (87%) of the canonical text? Wouldn’t it be more marketable if it was a paleo-Hebrew version of essentially the entire canonical text?” What would the forger’s intent be regarding the omission of so great a majority of the current text?

Well, one possibility is that he was trying to make it look exactly as it now appears to modern scholars: as an early version of Moses’ Moab speech, sans all the other material of the Torah. And what would the forger, particularly in the 1870s, be trying to sell potential buyers on with this abbreviated text? I say particularly in the 1870s because the documentary hypothesis (DH[xi]), which proposed multiple authors of the Pentateuch, and late (i.e. 7th-5th century BC) redactions, was only in its infancy[xii] in the late 1800s, and was seemingly contained within purely academic circles — not mainstream. Furthermore, modern textual criticism didn’t even exist then.

The point is that this forger would, therefore, have likely not even have heard mention of the multiple authors and late redaction theories of the day. He was more likely, therefore, to be in the mainstream in seeing the entire Pentateuch as the work of Moses.

So, if he actually wasn’t aware of the DH ideas (such as the Priestly or Deuteronomic authors) being worked out in his day, what story behind the forgery could he have been selling?

It almost seems to me that for the forgery claim to have any credibility it has to be assumed that the forger was an early scholar of the Hebrew Bible who was convinced of the DH hypothesis (after having been exposed to it in academia), who was perhaps promoting it in his academic circles, and so hopeful that his forgery would be interpreted as supporting his hypothesis. If he was an academic (as well as a skilled forger), then he might have been willing to simply get the scrolls “out there” (via a quick, inexpensive sale on the antiquities market) and hopefully accepted by scholars as authentic, despite his knowing that its dramatic difference from the canon would diminish its price.

This is the content question: why forge this abbreviated content?.

The process question is this: Why would a modern forger, intent on getting rich from selling his “products” spend the time and effort to produce these scroll strips, only to sell them for almost nothing (£300) to Shapira? If the seller was, or was an agent of, the forger (and not our hypothetical early DH scholar discussed above), then obviously the asking price would have been something substantial, to make it worth the effort and skill he had expended in its production that reflected the purported antiquity of the materials. But it wasn’t. (Note: Shapira later put a price on these same strips of £1,000,000 in discussions with the British Museum; over £31,000,000 in today’s currency, or nearly $40M.)

So, if the strips were forged, the process scenario only makes sense if the forger was no longer in the picture. Perhaps he died suddenly, and his agent was only trying to recover something for himself from their sale? Whatever, the forgery claim simply doesn’t hold up under common sense inquiry of the terms of the sales transaction if the forger was in it for the money (as 99.99% are).

The most rational possibility then, technical textual arguments notwithstanding, is that the scroll is authentic, actually found in a cave in what was Moab (now Jordan) and left there by an ancient author – if not Moses himself, then someone who was his close observer and scribe.

What’s NOT in the Scroll?

Lots of later redaction material is, of course, not in the scroll. But the most stunning omission is what is known as the “Law Code”, Deuteronomy chapters 12-26, acknowledged by most scholars to be a later insertion.

To see how later redactors inserted this material into the scroll to eventually result in Deuteronomy, we need to take a close look at its boundaries, and how the text on both “sides” of it may have once fit together precisely, before having been artificially bifurcated.

Referring to Table 1, you can scan halfway down the table and find that the last Dt. 11 entry (11.29-30) is followed immediately by Dt. 27:12-13. If these two fragments are read consecutively, you’ll notice that they fit together perfectly.

It was at this point that later priestly redactors apparently got out their pens, and inserted Dt. 11:31-32 and all of the Dt. 12-26 Law Code.

What was the law of Moses? The common assumption is that it was the entire Pentateuch. Most accept this on faith, lacking any other information.

What does it mean if this scroll is authentic and perhaps substantially pre-dates the canonical Deuteronomy (7th-5th century BC)? What conclusions can be drawn from this?

If the Moses Scroll predates Deuteronomy, what does it mean that Deuteronomy 12-26 – the “Law Code” — is completely missing from it?

Our first (and the easiest) conclusion is that Moses in writing his scroll knew nothing of the Law Code, and He personally was never given it by God. If he had been given it, then he would have recorded it in his scroll.

The Law Code seems to have been later inserted by agents of the Priesthood. At the time that it would have been inserted – likely the 7th century or so BC, the first temple had in theory been in operation for a couple of hundred years. And so what a great opportunity to get Moses’ endorsement, not only of the rule for exclusive centralized (i.e. Temple) worship, but also other rules typically associated with King Josiah’s reforms of the 7th century BC. (Josiah’s reforms may have been the purpose for suddenly “discovering” a perhaps redacted scroll of Moses [see 2 Kings 22:8-11] in the Temple in 625 BC.)

This scroll articulates both the curses for not following and the blessings for following each of its commands; essentially the Ten Words (i.e. “commandments”). But for some reason we find these command-by-command blessings missing from Deuteronomy. Why might that be? And what would be the implications of presenting these blessings as Moses’ Law and God’s covenant directly to the people?

Well, for one thing, the people would see that they had no need for the Priests to mediate between them and their God. If the Ten Words in the Moses Scroll spell out not only the curses for violating each command, but also the specific blessing for following each one, and each of those is presented directly to the people (as was done by Moses in Moab on the verge of their entry into Canaan), then why is it, exactly, that the people need to offer sacrifices to God? They already know how to live to garner His blessings. They don’t need to slaughter a goat to do that. And, as well, they know their standing with God if they violate those instructions.

So, what’s a sacrifice going to do for them? Importantly, God never specified the offering of propitiatory sacrificial offerings to Him to remediate an individual’s sins. The Law, having been completely laid out in the scroll for each of the Ten Words, is self-sufficient as a covenant of moral and ethical behavior and attitude. And it’s binary: no shades of grey. Obey the law; enjoy God’s consequent blessing. Violate the law; experience His curse. It’s simple and pure; no contingencies. (In an addendum we present each of the Ten Words, their blessings, and their curses from Nichols[iv].)

Where’s the role of a sacrifice in this Law? Uncomfortably, there isn’t any. The scroll makes no mention whatsoever of offerings or sacrifices. (To see why this omission is perfectly Biblical, you may want to have a look at an earlier piece I wrote: Did God Want a Temple, Sacrifices, or a Monarchy? Additionally, and surprisingly, there is no mention of circumcision as a requirement of the people in the land.)

Its premise seems to be: If you know what God requires of you, and what the consequences will be if you follow or, alternatively, violate His laws, then it is clear to everyone who knows this Law how they are to live, and how they will be treated by God for doing (or not doing) so. And, if there’s no role for sacrifices and offerings, then obviously there is no role for priests to offer those sacrifices on your behalf (while enjoying the majority of them for their own benefit), nor for the edifice of a Temple at which to make those offerings.

What’s in the Scroll that Isn’t in Deuteronomy?

What the later editors removed, however, is equally significant. Again, referring to Table 1, notice that following the entry for Dt. 27:14 comes the set of “Blessed Be” verses that spell out the blessing for each commandment when it has been followed.

Assuming the scroll predates Deuteronomy, why remove these? Why withhold this information from the people that they will be blessed by God for adhering to His Law?

This is puzzling. One could take the cynical view that the priests didn’t want the people to know that they could follow God’s Law, and so live in His blessing. If they didn’t know they could follow it, then they would be dependent on the priests to prescribe the sacrifices and offerings they needed to make when, in fact, they didn’t follow it.

A more practical assessment, however, may be that by the time the priests added the Law Code to Moses’ scroll, the people had a long-established pattern of violating God’s Law. So to the priests, the prospect of the people actually following that Law was only an ideal, not something that they should actually expect. This may also be the explanation for their omission of the verses in the scroll that immediately follow that identified as Dt. 4:23/5:8. Since they had long violated God’s Law, they may have concluded that it served little purpose to insert His admonitions in these verses to follow it.

It’s interesting, further, that the priestly redactors kept the theme of the scroll’s curses (Dt. 28) – those things that would require the priests to intervene with God to supposedly minimize their impact via some Temple propitiation on behalf of the violator.

The Lying Pen of the Scribes

You’re probably familiar with the story (mentioned above) of Moses’ scroll being “found” in the Temple by Hilkiah during King Josiah’s reign, and his stricken reaction to hearing it. It seems whatever the generations prior to Josiah’s had been doing, it wasn’t in accordance with the contents of the newly “discovered” scroll of Moses.

Jeremiah, a contemporary of Josiah, knew of this apostasy. And he tells us in Je 8:8:

[8] “How can you say, ‘We are wise,

and the law of the LORD is with us’?

But behold, the lying pen of the scribes

has made it into a lie.

Read Jeremiah 8. It seems to be an all-encompassing condemnation against Israel. Why? Apparently, because their scribes had concocted a version of “the law of the LORD” that was their creation; not the Law given by God.

What’s the Difference?

What is lost if, assuming the Shapira scroll text is Moses’ — the original Deuteronomy — we have to reconsider what the historical story of Israel is, distilled down to its fundamental Exodus-to-land story in which the requirements of Israel’s LORD are extremely clear and straightforward?

I suppose the answer to that depends, first, on whether you are Jewish or not. If you’re Jewish, either everything changes, or essentially nothing changes. If you’re observant, Reformed, or especially Orthodox, then vast tracts of not only the Pentateuch, but all of the Mishnah’s Rabbinic writings stemming from it are suddenly of significantly different value than previously. However, if you’re not particularly “Torah observant” as a Jew, then maybe nothing has changed. After all, you still have your heritage, and your traditions, and your family. And for most Jews, those are the valuable things. The Torah and the writings are for Rabbis.

If you’re not Jewish, we similarly have the possibility of two dramatically different responses. First, Fundamentalist Christians might have a serious, serious problem to wrestle with, not because the Torah has anything to do with their lives or their professed faith, but because it means there is content in the Bible that inaccurately portrays God’s will and heart. Or does it?

I make the point regarding the fundamentalist understanding of these ideas of “inerrancy” (which itself is not a Biblically-attested concept), and the Bible text’s “inspiration” (by which they understand God prompting the authors of the Bible to write His words), in “God’s Issues With the Temple Cult”:

“First, I believe all of the Bible was prompted by God, YHWH. And while He didn’t dictate to some ancient stenographers, He did prompt (or at least permit) its authors to write what they ended up writing. How do we know this? Because we can hold it in our hands today. If God didn’t want said what is said, it wouldn’t say it.”

Also, the Christians identified as Dispensationalists, as well as some fringe Orthodox Jews, would be quite disappointed to find that God’s Law — the “Law of Moses” — had nothing to do with sacrifices or a Temple. Many of these are waiting for a new Temple to be built in Jerusalem today.

On the other hand, a significant portion of Christians would, I believe, be edified to learn of this same fact, as they would see clearly that the heart of YHWH for His people is the same heart they are familiar with in Jesus.

I think our traditional views of scripture need to be freed from the handcuffs with which we’ve shackled them and be allowed to mature, instead, into a seeking and a reverence for God’s heart that is revealed in His Word.

God had His reasons for letting the Priestly influence transform Moses’ words (if, in fact, the Shapira Scrolls are authentically Moses’ words at Moab) into what we have in Deuteronomy today, not to mention Leviticus and Numbers. That influence didn’t “sneak one by” God. He knew full well what was going on and He had His own reasons for their influence showing up throughout the Torah.

And what were those reasons? I believe, first, it was to show their utter futility in retrospect. (The following is from the same piece cited above:)

“Their priests constructed a religious system – the temple Cult – to try to manage (if not control) the people’s penchant for ignoring God’s instructions (though they did literally nothing to encourage the people’s love of YHWH).

But it did no good. While the people may have, at least for a time, followed the sacrificial rules of the priests and their calendar of festivals (often erroneously termed the “Mosaic Law”. More on this in an upcoming piece), they apparently at no time (as a people) lived as God, through His Prophets, had instructed them to live. This is the unmistakable takeaway from the Levitical Torah, whoever wrote it — its system’s utter futility. Its words and system proved worthless in guiding the people into a more reverential, more obedient, personal relationship with God (except for a tiny, faithful remnant).”

Additionally, the inclusion of the Torah’s priestly material has had the effect of dramatically emphasizing the contrast between the God portrayed in their texts, and the one found not only in the early chapters of Deuteronomy, but throughout the Prophets, Psalms, and Wisdom literature.

Second, I believe the Priestly material in the Torah serves as our object lesson in the need for ritual purity encompassing God’s place of habitation. This idea becomes central to interpreting some of the New Testament narrative.

Try To Imagine

Please open up the Ten Words table, scan through it again, and then try to imagine the impact on our civilization of internalizing the utter beauty and simplicity of lives lived in obedience to these commands. True, people are still people, with natural tendencies to violate each and every one of these rules, and regularly.

But purely as a revelation of God’s heart for His people, try to imagine all the doctrinal noise that would be immediately silenced, all of the political posturing that would be made subject to scorn, all of the legislative and executive order chicanery that would be rejected when injustice was its result. Imagine the impact of this simple, powerful, moral authority being diffused throughout the world’s societies — convicting them of the “weightier matters of the Law”.

Even without the indwelling of the Spirit of God sent from Christ into His followers (which, of course, is a practical necessity to enable us to live out these commands), I contend that the power of this message would have an overwhelmingly positive influence on virtually all aspects of civil society.

Open Questions

All we’ve done here is open up the possibility that Shapira’s Scroll was authentic and a precursor of today’s Deuteronomy, containing the instructions from Moses to Israel before they entered the promised land. If we stipulate that it is authentic, several areas of inquiry and rethinking long-established conventions and interpretations immediately surface.

The first, which I want to personally pursue, is to investigate the extent to which if at all, the New Testament’s references to Tanakh verses need some reinterpretation. Specifically, I wonder when Jesus referred to the “Law”, what text was He referring to? Same for Paul. I think I know. However, each will have to be evaluated individually in its particular context.

Next, the scroll’s Ten Words are different from either the list in Exodus 20 or in Deuteronomy 5. What can we learn about later redactors and their mindsets if the scroll’s list is their precursor? Or are these differences merely technical, or cosmetic?

I’m intrigued, for example, by the Blessing associated with the command “You shall not hate your brother in your heart. I am Elohim your Elohim” which says “Blessed is the man who loves his neighbor”. Where else in the Bible do we find God’s admonition to “love your neighbor”? Well, famously, Leviticus 19:18b which is where many of us thought Jesus got His answer to the Pharisee’s question in Mt 22:39. But is it?

If God gave Moses these blessings to recite to Israel at Moab, how do we know Jesus didn’t know them? For that matter, how can it be that Lev 19:18 buries this admonition (as a kind of afterthought) while Jesus says it is “like” the admonition to “love the LORD with all your heart, and with all your mind, and with all your everything”?

My point is that there is a real mystery as to the source of the command to love your neighbor/brother. Jesus didn’t invent it. He cited it. But from where, and from what knowledge?

Perhaps most profoundly, if the Shapira scroll is authentically Moses’ words at Moab, what does this tell us about Jesus’ message vs the Torah’s (authentic, God-inspired) message? This is a question several early examiners immediately considered as a motivation for its forgery – that it validated Jesus’ message and His disruption of the commercial enterprise of His days’ Temple (Shapira was a Christian convert from Judaism). Since many of these examiners were Jewish, they concluded that the scroll’s text was a Christian-inspired forgery.

But what if it wasn’t? What does it imply about the veracity of Christ’s implicit claim to be the Son of God (Mt 4:7, Jn 1:50, Mt 26:64, Jn 8:58)? What is the relationship between Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount’s Beatitudes and the “Blessed be’s” of the scroll, and the relationship of their respective authors? Can we find connections other than spiritual? It’s definitely worth an investigation.

Conclusion

The Shapira “Moses” scroll text raises a wide range of questions. If it is a forgery, what was the forger’s motive? If it is authentic, then what Jewish and Christian beliefs and doctrines need to be rethought?

[i] To this day he is still engaged in research that will hopefully one day identify the whereabouts of the now- ( and since 1897)missing scroll fragments.

[ii] Nichols, Ross K., The Moses Scroll, Horeb Press, 2021.

[iii] I think it is important to understand the cultural dynamic of the day. The whole movement of “Biblical Archaeology” and the frenzied search for Biblical artifacts was ramping up to a kind of frenzy. The Bedouins quickly figured out that there were Europeans willing to give them money for artifacts that were at least alleged to be ancient – possibly Biblical. So, the Bedouins not only went searching for such things around them, but in some cases ended up manufacturing them.

[iv] Guthe, Hermann, Fragments of a Leather Manuscript, Horeb Press, 2022

[v] Shapira Scroll – Wikipedia

[vi] Dershowitz, Idan, and Na’ama Pat-El. The Valediction of Moses: A Proto-Biblical Book [Place of publication not identified]: Mohr Siebeck, 2021, ISBN 978-3-16-160644-1. Dershowitz’s conclusion regarding the scrolls, as the title of his book implies, is that it was authentic and, in fact, “proto-biblical” (i.e. existing before at least many of the other scrolls of the Bible did.)

[vii] Shlomo Guil (2017) The Shapira Scroll was an Authentic Dead Sea Scroll, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 149:1, 6-27, DOI: 10.1080/00310328.2016.1185895

[viii] Nichols, Ross K, The Moses Scroll, p28

[ix] Reiner, Fred, Tracking the Shapira Case: A Biblical Scandal Revisited, BAS Library, 1997

[x] “Complete” here means it starts with the introduction of Moses with Israel in Moab, and it ends with the 120-year-old Moses saying he wouldn’t be entering the land with them (plus a redacted postscript)—the entire scope of the Moses speech we think of as Deuteronomy.

[xi] The Documentary Hypothesis theorizes that possibly three or more different editors produced Deuteronomy. Its conclusion is that two text-production sequences (DTR1 and DTR2) produced Deuteronomy’s first 11 chapters and substantially all of chapters 27-32, while a third (simply “D”) produced the remainder of the chapters, including most of the Law Code..

[xii] Julius Wellhausen didn’t publish his “History of Israel, Vol 1” in which much of the DH thinking of the time was accessibly laid out, thereby allowing it to be taken up by non-academics, until 1878,

[xiii] Nichols, Ross K., The Decalogue of Moses W Shapira’s Leather Strips, Academia.edu, 2021

Leave a comment