Introduction

I spend virtually zero time reading the Talmud. However, I recently stumbled onto a video presentation that describes some radically strange stuff there having to do with the Yom Kippur ceremony, especially after 30 AD. Especially for Christians, this is a very interesting piece of Jewish legend.

Background

The Talmud

The Jewish Talmud is a written record of two thought-to-be-ancient texts from different textual sources. The first, called the Mishna, is thought in Judaism to represent their Oral Torah finally written down early in the first millennium AD, redacted around 200 CE by Rabbi Judah the Prince. It consists of six orders (Sedarim), covering various aspects of Jewish law, ethics, and rituals.

What is the “Oral Torah” you ask? In Judaism, the Oral Torah is thought to be those commands of God given to Moses during the Exodus but that he did not write down. Jews believe these laws got passed down orally through the generations, starting with Joshua[i]. (I’ve written a bit about Torah and Oral Torah development practices in: “What Did the “Law of Moses” Mean to – the Israelites?”.)

The other major component of the Talmud is called the Gemara. It is a commentary and analysis of the Mishnah, compiled between 300–500 CE. It includes discussions by Amoraic sages in Babylonia and Eretz Yisrael, expanding on the Mishnah with legal interpretations, stories, and theological insights.

Within the Talmud document, both sources have been compiled together by topic. The Babylonian Talmud is thought to have first been produced in the mid-sixth century AD.

Our interest for this discussion is the Talmud tract called “Yoma” having to do with the practices of Yom Kippur.

Yom Kippur

The Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur (Yom HaKippurim – Day of Atonement) is the culmination of ten High Holy days kicked off by Rosh Hashana and characterized by repentant prayers for forgiveness, and a fast on the day of Yom Kippur. It is an annual rite that commemorates and symbolizes the forgiveness of the sins of the Jews. In Judaism, the day commemorates God’s forgiveness of the Israelites at Sinai following the molten calf incident, as announced by Moses on his second return down from the mountain with the second set of tablets.

The Scapegoat Ritual

The scapegoat ritual is described in the Hebrew Bible substantially in Leviticus 16.

Click on this line to read the applicable verses (Lev 16:6-10, 20-22,34).

6“Aaron shall offer the bull as a sin offering for himself and shall make atonement for himself and for his house. 7Then he shall take the two goats and set them before the LORD at the entrance of the tent of meeting. 8And Aaron shall cast lots over the two goats, one lot for the LORD and the other lot for Azazel. 9And Aaron shall present the goat on which the lot fell for the LORD and use it as a sin offering, 10but the goat on which the lot fell for Azazel shall be presented alive before the LORD to make atonement over it, that it may be sent away into the wilderness to Azazel.

20“And when he has made an end of atoning for the Holy Place and the tent of meeting and the altar, he shall present the live goat. 21And Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins. And he shall put them on the head of the goat and send it away into the wilderness by the hand of a man who is in readiness. 22The goat shall bear all their iniquities on itself to a remote area, and he shall let the goat go free in the wilderness.

34And this shall be a statute forever for you, that atonement may be made for the people of Israel once in the year because of all their sins.” And Aaron did as the LORD commanded Moses.

We see that two goats are involved in this ceremony. Each will play a different role. So, the first order of business is for the High Priest to distinguish between them by drawing a lot. The Yoma tract describes this procedure as two pieces of paper being placed into a plain box. On one is written “To the LORD”, and on the other “To Azazel”.

The fate of the goat chosen “to the LORD” is to be slaughtered as a sin offering for the people by the priests. The fate of the Azazel goat is different.

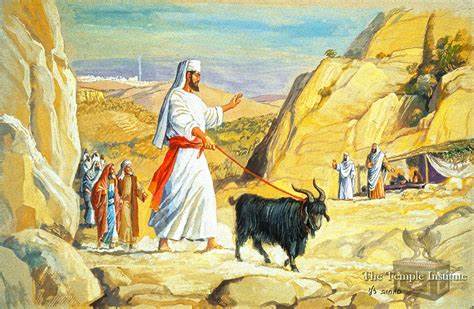

The priest symbolically transferred the (unknown) sins of the people onto the “to Azazel” goat by laying both his hands on its head and praying for Israel’s sins to be removed by God. This now-“scapegoat” is then led away into the wilderness – possibly to be thrown off a cliff, or possibly to be simply abandoned and left to his fate among the wild animals. But in any case, as the bearer of the people’s sins, he is removed far away from not only the people, but, importantly, proximity to the Tabernacle/Temple.

Now there’s no consensus as to what the term “Azazel” represents here. Commentaries range from a “desert demon”, to “scapegoat” itself, to “a high rocky outcrop” or “cliff.[ii] What is clear is that whatever the fate of the goat, and by whatever means, he was led to the wilderness and left with Israel’s sins, as seen by its priests, far away from the camp of Israel and their God.

So, what did the rabbis who wrote the Mishna and Gemara say about this ceremony? This is where the story gets good.

Talmud Tract Yoma

In Chapter 4 of the Yoma tract, the authors take up not simply an elaboration of the scapegoat process, but far, far more intriguingly, some history of the practice during and after the life of Simeon the Upright, the High Priest of Israel in the 3rd century BC, and then yet a new twist on the ceremony’s history following 30 AD, up to the time of the Temple’s destruction in 70 AD.

The Drawing of Lots

It is not at all clear to me what this process physically looked like.

(I’ve provided the text of the Talmud in this drop-down preceding this discussion of the lots so you can read it for yourself and see if you can figure out what they’re saying!!![iii])

MISHNA: He shook the box, and took out two lots. On one is written, “to Jehovah”; on the other is written, “to Azazel.” The Segan is at his right, and the head of the family [see above] on his left. If that of Jehovah was taken up by his right hand, the Segan says to him, “My lord the high-priest, raise thy right hand.” If that of Jehovah was taken up by his left hand, the head of the family addresses him: “My lord the high-priest, raise thy left hand.” He placed them [the lots] on the two he-goats, and uttered: “To Jehovah a sin-offering.” R. Ishmael says: It was not necessary for him to say “sin-offering,” but “to Jehovah” sufficed. They responded: “Blessed be the name of His kingdom’s glory for ever.”

GEMARA: Why had he to shake the box? That he should not have intentionally taken that for Jehovah in his right hand (as it was a good omen if he took it up by chance). Rabh said: The box was of wood, and was not sacred, and could contain only the two palms of the hand. Rabbina opposed: It is right that it had only capacity for the two palms, that he might not intentionally take the lot for the Lord; but if it was profane, he should have sanctified it? The answer is: If he had sanctified it, it would have been a wooden sacred vessel, and in the Temple wooden sacred vessels were not used. Let them have made it of silver or gold? Because the Torah wished to spare the wealth of Israel. The Mishna is at variance with the Tana of the following Boraitha: R. Jehudah says in the name of R. Eliezer: The Segan and the high-priest both placed their hands in the box. When that for Jehovah was picked up by the high-priest, the Segan said to him: “Mylord the high-priest, raise thy right hand.” But if it was picked up by the Segan, the chief of the family said to him: “Speak thy words.” Why not the Segan himself? The lot came into the hand of the Segan, and

p. 59

not of the high-priest; therefore the spirits of the latter would have been depressed. On what point do they differ? One thinks, the right hand of the Segan is better than the left hand of the high-priest, and therefore both should put into the box their right hand; whereas the other thinks that the left hand of the high-priest is as good as the right hand of the Segan, and therefore he ought to place both his hands in the box. And who is the Tana who differs from R. Jehudah? That is R. Hanina, the Segan of the priests. As we have learned in the following Boraitha: R. Hanina the Segan of the priests said: Why did the Segan ever walk on the right of the high priest? In case the high priest became unfit for service, the Segan should enter at once to do the service.

The process seems to involve the High Priest picking two pieces of paper (lots) from a box – one with his right hand, and one with his left. Also apparently, in front of him were the two goats one on his left and one on his right, so the goat to his right was designated in accordance with the destiny described by the slip in his right hand – either the scapegoat or the goat to be sacrificed.

Secondly, according to the Talmud, a string of crimson yarn was cut in two: one half was used as a leash around the scapegoat’s neck; the other was placed in the Temple. After a set period of time, if the yarn in the Temple turned white it was a sign that the people’s sins had been forgiven in the Yom Kippur ritual. But, the reverse was also true.

Third, the Westernmost light of the Temple Menorah would, under conditions thought to be favorable from God, remain lit even if the flames of the other branches went out, and so be used to rekindle the other lights of the Menorah. If, however, this Westernmost light went out, it was a very bad omen.

At this point, the Talmud on this subject begins its retrospective on how things were during and after Simeon’s life, and following 30 AD, starting with the drawing of lots.

It was seen (according to these 2nd-3rd century rabbis) as a good omen if the High Priest pulled out the “to the Lord” token with his right hand, but not if it came out in his left.

“The rabbis taught: In the time of the forty years during which Simeon the Upright was high priest, the lot for Jehovah always came into the high-priest’s right hand, but thereafter it sometimes fell into his right, sometimes into his left hand. And the tongue of crimson wool, during the time of Simeon the Upright, always became white. But after Simeon the Upright, sometimes it became white, sometimes it remained red.

In Simeon the Upright’s time the western light ever burned, but after him it sometimes burned and sometimes went out.

The fire of the altar ever waxed in strength, and except the two measures of wood prescribed they had not to add any wood, in Simeon the Upright’s time; but after him, sometimes the fire persisted and sometimes wood had to be added. In his time a blessing was sent into the Omer, the two loaves of bread, and the showbread, and every priest who received only the size of an olive became satiated, and some was left over; but after him, these things were cursed, and every priest got only the size of a bean. And the delicate priests refused to take it altogether, but the voracious ones accepted and consumed. It once happened, one took his own share and his fellow’s: he was nicknamed “robber” till his death. The rabbis taught:

The year when Simeon the Upright had to die, he told the sages: “Children, know ye that this year I am going to die.” They asked him: “How dost thou know?” He said: “Every year when I entered and left the Holy of Holies, I was accompanied by one old man, dressed in white and enveloped in white; but this year it was an old man attired in black and in a black turban, and he entered with me but did not go out with me.” And after the festivals, he got sick, and died.

And thenceforth priests ceased to bless Israel with the name of Jehovah, but used “Adonai” (the Lord). The rabbis taught: Forty years before the Temple was destroyed, the lot never came into the right hand, the red wool did not become white, the western light did not burn, and the gates of the Temple opened of themselves, till the time that R. Johanan b. Zakkai rebuked them, saying: “Temple, Temple, why alarmest thou us? We know that thou art destined to be destroyed. For of thee hath prophesied Zechariah ben Iddo [Zech. xi. 1]: ‘Open thy doors, O Lebanon, and the fire shall eat thy cedars.’”[iv] Note also here the story of the Temple’s gates, usually requiring several men to open, but after 30 AD occasionally just opening by themselves.

The Talmud describes several strange occurrences noted by the rabbis that began following the death of Simeon (here called “the Upright” but elsewhere “the Righteous” or the “Just”) sometime in the 3rd century BC. However, following 30 AD, these “good omens” stopped entirely.

First, the High Priest always ended up with the scapegoat (Azazel) lot in his right hand, not the lot of the sacrifice to the LORD – seen to be a bad sign.

Next, the cut crimson cord portion that was left in the Temple did not turn white (indicating failure to forgive Israel’s sins).

Next, the Westernmost lamp of the Menorah, which traditionally remained perpetually lit, and from which the other lamps were occasionally rekindled, consistently went out.

Also, no longer were two “measures of wood” adequate to keep the altar fire burning.

And, lastly, randomly, the gates of the Temple would open themselves.

Apparently, all of these thought-to-be-negative signs occurred consistently following 30 AD (at least as far as the 2nd-3rd century authors of the Talmud knew).

Takeaways

Right, wrong, or indifferent, according to the rabbis in the early centuries of the new millennium that followed 30 AD, and extending to the destruction of the Temple (and Jerusalem) in 70 AD, things “went south” for the Yom Kippur ritual.

It’s more than curious that 30 AD is the date that many Biblical scholars identify as the year of Jesus’s death and resurrection.

Why might it be that God, in His own subtle, but unmistakable way, communicated with the Priests of the Temple in Jerusalem following 30 AD that something just wasn’t right about their Yom Kippur ceremony? Might it have been that, following Christ’s death and resurrection, the Yom Kippur ritual was no longer effectual (if it was ever more than symbolic) for expiating Israel’s sins? Might it have been that the ultimate atonement and reconciliation had happened through Jesus of Nazareth’s death and resurrection?

No? Then what were these reports about? What was their cause? And why did the authors of the Talmud think them significant enough to warrant mention? Is there some other event in Judaic history that occurred in 30 AD that might be identified as the cause of these phenomena?

If you’re a Christian, I think your left with a tantalizing takeaway that confirms that God was done with the symbol of forgiving Israel’s sins through a goat, starting in 30 AD. (As you might imagine, Jews can get very angry at any Christian interpretation of these signs.)

If you’re a rabbinic Jew, I’m not sure what you’ll think, or rationalize, about this report. Several rabbis/scribes were impacted enough by the historical reports of this phenomenon that they were convinced to record it in their Talmud. Why? Did they have some ulterior motive to benefit themselves or their point of view? What might that be? There doesn’t appear to be an “us versus them” issue in this portion of the Yoma tract. Rather, it appears to be, as much as possible, a simple retelling of the history of some extremely strange events that they were, like we are now, left to at least consider a possible meaning for and the implications of.

[i] I simply couldn’t believe this when I first learned it. And I still can’t.

[ii] My interpretation is that the word represents the conjunction of two words: 1) Azaz, meaning something like strong or mighty, and El, of course being a name for God. Putting the two together you get the image of the goat being taken out to a mighty (perhaps wrathful, but in any case righteous) God to receive the judgment that otherwise would have been dispensed on the Israelites.

[iii] The term in this Talmudic text “Segan” is a title for an assistant High Priest

[iv] Re: this Talmudic passage, “Simeon the Upright” was the High Priest of Israel in the 3rd century BC — the pinnacle of Temple Judaism.