Introduction

The “Synoptic Problem” is not a “problem” but a question: “How is it that we have three Gospels relating many of the same stories and sayings of Jesus in sometimes near-identical words?” Did they copy from each other? Did they copy from some common source we no longer have? And of these Gospels, which was written first?

Conventional Wisdom

The conventional wisdom on the subject of the order of Gospel authorship is that Mark was first. This is the conventional conclusion for a couple of reasons.

First, Mark is, by word count, the shortest of the Synoptics. So, it stands to reason that the other Gospels, being later, made use of Mark and embellished upon it, leading to longer narratives. The “coarseness” and colloquial nature of Mark’s language also left the impression of its more primitive origin.

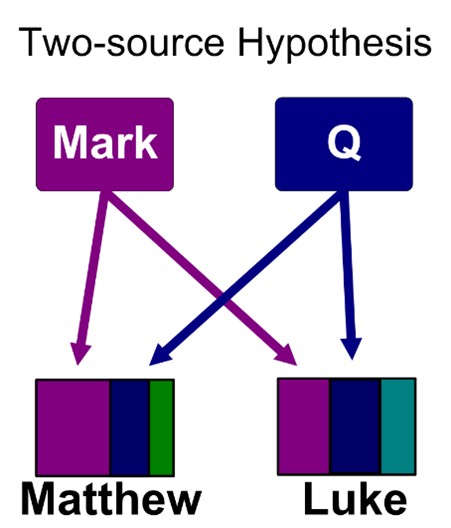

To answer the question as to why Luke and Matthew contain narrative fragments (“pericopae”) not found in Mark, they needed to postulate another source that those two had access to but that Mark did not. That source they labelled Q (from the German “quell”, meaning “source”). Q, then, was invented as the (hypothetical) source of the texts common to Matthew and Luke but not Mark, as indicated in the adjoining figure.

Evidence for Luke Being the First Written Gospel

Background of the View

In the mid 1960’s, Robert Lindsey[i],[ii], a biblical scholar and pastor in Jerusalem, took on the job of producing a new Hebrew translation of the Greek Gospels, ostensibly to augment the version produced by Franz Delitzsch in the 1800’s. It was (and remains) widely believed that the Gospels started out as Hebrew manuscripts, so that reverse engineering them from the Greek back to their original language would reveal insights masked by the Greek.

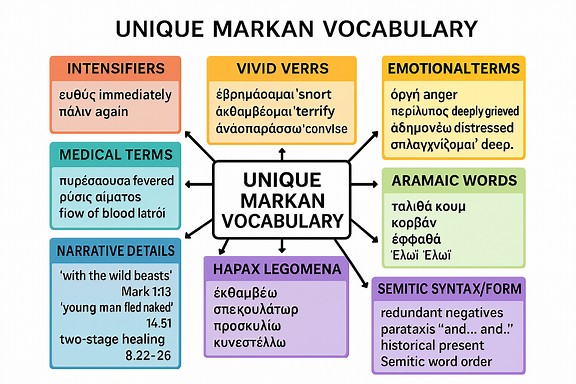

Lindsey started with Mark, as it was widely assumed to be the first-written. In the course of this work, he noted several anomalies of language that were essentially unique to Mark (though a few were replicated in Matthew). Luke, significantly, nearly completely avoided these strange phrases and vocabulary.

If Mark came first and served as a source for Matthew and Luke, how is it, Lindsey wondered, that Luke copied essentially none of Mark’s strange language, yet in other respects (the 77 common pericopae and their sequence) seemed to faithfully follow Mark’s lead?

This questioning led him to theorize that perhaps Mark wasn’t written first (the accepted view, called “Markan Priority”). Perhaps Luke was first (“Lukan Priority”). His theory assumed the name the “Jerusalem School Hypothesis” (or just “Jerusalem School”), and proceeded to attract other scholars in Jerusalem (e.g., David Flusser, David Bivin, and Stephen Notley) into this work.

Evidence Sparking Lukan Priority Speculation

Linsey’s translation of Mark’s Greek into Hebrew revealed some odd Hebrew phraseology – either phrases that were used over and over (e.g., καὶ εὐθύς – “and immediately”) that were not normally used in Hebraic/Semitic writings, or simply clumsy phrases which Matthew only replicated sparingly (refining the texts of the remainder) and Luke essentially replaced, often with “Hebraisms” that converted smoothly as Hebrew terms, phrases, or idioms.

I’ve listed some of these terms and phrases unique to Mark, which you can examine by clicking on this text.

🗺️ A MAP OF UNIQUE MARKAN VOCABULARY

(Words used by Mark that Matthew and Luke do not use in parallel passages — or at all)

I’ll group these into functional categories, because that’s where the real insight lies.

1. Mark’s Favorite Intensifiers & Adverbs

Mark loves vivid, urgent language.

🔹 εὐθύς — “immediately”

- Mark uses it over 40 times.

- Matthew drastically reduces it; Luke nearly eliminates it.

- This is one of Mark’s most famous stylistic fingerprints.

🔹 πάλιν — “again”

- Mark uses it frequently to create narrative rhythm.

- Matthew/Luke often omit it.

🔹 εὐθέως — another form of “immediately”

- Mark uses both εὐθύς and εὐθέως; Matthew/Luke prefers only one form or avoids both.

2. Mark’s Vivid, Colloquial Verbs

These often sound rough or dramatic.

🔹 ἐμβριμάομαι — “to snort, scold harshly”

- Used of Jesus (Mark 1:43; 14:5).

- Matthew/Luke avoid this verb entirely.

🔹 ἐκθαμβέομαι — “to be greatly astonished/terrified”

- Mark 9:15; 14:33; 16:5–6.

- Not used by Matthew or Luke.

🔹 κρατέω in narrative action scenes

- Mark uses it frequently for “seize, grab.”

- Matthew/Luke often substitute milder verbs.

🔹 ἀνασπαράσσω — “to convulse violently”

- Mark 1:26.

- Unique to Mark.

3. Mark’s Emotional Vocabulary

Mark portrays Jesus and others with unusually strong emotional terms.

🔹 σπλαγχνίζομαι — “to feel deep compassion.”

- Mark uses it in key scenes (1:41; 6:34; 8:2).

- Matthew uses it, but often in different contexts; Luke rarely uses it of Jesus.

🔹 λυπέομαι / ἀδημονέω / περίλυπος

- Mark clusters these in Gethsemane (14:33–34).

- Matthew/Luke smooth or reduce the emotional intensity.

🔹 ὀργή / ὀργίζομαι — “anger”

- Mark 3:5 uniquely attributes anger to Jesus.

- Matthew/Luke omit the term.

4. Mark’s Medical Vocabulary

Mark’s healing stories contain technical or semi-technical terms.

🔹 πυρέσσουσα — “fevered woman” (1:30)

- Mark uses a medical participle; Matthew simplifies.

🔹 ῥύσις αἵματος — “flow of blood” (5:29)

- Mark’s phrasing is more clinical than Matthew’s.

🔹 ἰατρός references

- Mark 5:26 includes a digression about physicians; Matthew/Luke omit or soften.

5. Mark’s Latin Loanwords

Mark uses more Latinisms than Matthew or Luke — a sign of a Roman audience or Roman setting.

Examples

- κεντυρίων — centurion (Latin loanword)

- λεγεών — legion

- πραῖτωρ — praetorium

- σπεκουλάτωρ — executioner

- ξέστης — measuring vessel (Latin sextarius)

Matthew/Luke often replace these with Greek equivalents.

6. Mark’s Aramaic Words (with explanations)

These are unique to Mark and signal a Semitic substrate.

Examples

- ταλιθά κουμ (5:41)

- κορβᾶν (7:11)

- ἐφφαθά (7:34)

- Ἐλωΐ Ἐλωΐ (15:34)

Matthew/Luke either omit or modify.

7. Mark’s Unique Nouns & Descriptive Terms

🔹 σπυρίς — “large basket” (8:8, 20)

- Matthew uses it in a different context; Luke avoids it.

🔹 χορτάζω in feeding scenes

- Mark uses it in a vivid, physical sense.

🔹 κράβαττος — “pallet, mat”

- Mark uses this colloquial term; Matthew/Luke prefer κλίνη.

🔹 ἄγριος — “wild” (as in “wild beasts,” 1:13)

- Unique Markan detail.

8. Mark’s Narrative Connectors & Scene‑Setting Vocabulary

🔹 πάλιν — “again”

- Mark uses it to create a looping narrative rhythm.

🔹 ὁδός — “the way/road”

- Mark uses it symbolically (discipleship motif).

- Matthew/Luke often shift the metaphor.

🔹 εὐθύς / εὐθέως

- Already noted, but central to Mark’s narrative tempo.

9. Mark’s Unique Phrases (Not Just Words)

These are idiomatic expressions Matthew/Luke avoid.

🔹 “he was with the wild beasts” (1:13)

🔹 “he looked around with anger” (3:5)

🔹 “he began to teach them many things” (6:34)

🔹 “for they did not understand about the loaves” (6:52)

🔹 “the young man fled naked” (14:51–52)

These are stylistically Markan even when the vocabulary is not unique.

10. Mark’s Hapax Legomena (words used only once in the NT)

A few examples:

- ἐκθαμβέω (astonish/terrify)

- σπεκουλάτωρ (executioner)

- ἀνασπαράσσω (convulse violently)

- προσκυλίω (roll toward)

- συνεστέλλω (warn strictly)

These are strong fingerprints of Mark’s style.

11. Ευαγγέλιο – Evangelion or “Good News”

Mark uses the term, likely coined by Paul, eight times, six in the voice of Jesus. Matthew uses it four times, two in the voice of Jesus. The term is found only one time in the LXX (2 Sam 4:10), and there it translates the Hebrew term 1319. בָּשַׂר bāśar, which simply means bring news or bear tidings (used 21 times in the Tanakh). The term is not used in the book of Luke (though its author knows the term, using it twice in Acts in the voices of Peter and Paul). It is reasonable, therefore, to conclude that evangelion did not appear in Luke’s sources.

🧩 Summary Table: Mark’s Unique Vocabulary Patterns

| Category | Mark’s Distinctive Feature | Matthew/Luke Response |

| Intensifiers | εὐθύς, πάλιν | Reduce or omit |

| Colloquial verbs | ἐμβριμάομαι, ἐκθαμβέομαι | Avoid |

| Emotional terms | anger, distress, compassion | Tone down |

| Medical terms | technical vocabulary | Simplify |

| Latinisms | κεντυρίων, σπεκουλάτωρ | Replace with Greek |

| Aramaic | Talitha, Ephphatha | Omit or modify |

| Narrative details | vivid, abrupt | Smooth or omit |

| Hapax legomena | rare words | Not used |

Luke contains essentially none of Mark’s awkward Greek. So, Lindsey reasoned, it was unlikely that Luke had ‘copied’ Mark for their common texts as was widely believed. And, if Luke didn’t “copy” Mark, maybe Mark wasn’t even in existence when Luke was written, or at least Luke’s author didn’t know of it.

Luke’s Gospel, on the other hand, was characterized by very clear Semitic forms represented in its Greek.

To review examples of the Hebraisms found in Luke, click on this text.

Major Categories of Hebraisms in Luke’s Gospel

Sources Used:

- David Bivin’s analysis of Luke 9:51–56[iii]

- R. Steven Notley’s study of “Non-Septuagintal Hebraisms” in Luke[iv]

- LukePrimacy.com’s catalog of Semitisms in “Special Luke”[v]

Semitic Syntax Embedded in Greek

These are Greek constructions that are awkward or unnatural in Greek but normal in Hebrew.

Examples (from Bivin and Notley):

- Use of “and it happened that…” (Hebrew wayehi) Luke frequently uses this narrative formula, which is idiomatic Hebrew but clumsy Greek.

- Parataxis (stringing clauses with “and”) Hebrew narrative style uses waw‑consecutive; Luke imitates this pattern.

- Redundant pronouns Hebrew often repeats the subject pronoun for emphasis; Luke does this in places where Greek normally would not.

These features are especially dense in Luke 9:51–56, which Bivin uses as a case study.

Semitic Phrases and Loan-Translations

Luke uses Greek words in ways that reflect Hebrew idioms rather than Greek idioms.

Examples:

- “Set his face to go to Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51) A literal rendering of Hebrew שׂוּם פָּנִים (“to set one’s face”), noted by Bivin as a Hebraism.

- “Son of peace” (Luke 10:6) A Semitic genitive construction meaning “peaceful person.”

- “Lifted up his voice and said” A Hebrew idiom (נָשָׂא קוֹל) rendered literally into Greek.

Notley emphasizes that many of these are not Septuagintal Greek but reflect non-LXX Semitic usage, suggesting a Hebrew rather than Aramaic substrate.

Semitic Word Order

Luke sometimes uses Hebrew-style word order:

- Verb–subject–object sequences

- Fronting of verbs or objects for emphasis

- “Behold” (ἰδού) used as a discourse marker, mirroring Hebrew הִנֵּה

These patterns are common in Luke’s narrative sections and are highlighted in both Bivin’s and Notley’s analyses.

Semitic Idioms Preserved in Greek

David Bivin’s broader work on Hebrew idioms in the Gospels lists many idioms that appear in Luke’s Greek.

Examples include:

- “Answering, he said…” A Hebrew idiom (וַיַּעַן וַיֹּאמֶר) even when no question was asked.

- “To find favor in someone’s eyes” A literal Hebrew idiom preserved in Greek.

- “To speak to the heart” Another Hebraic expression rendered literally.

These idioms often sound strange in Greek but natural in Hebrew.

Semitic Narrative Style

Luke’s storytelling sometimes mirrors Hebrew narrative conventions:

- Repetition of key words (Hebrew leitwort technique)

- Use of summary statements (“And he went… and he taught…”)

- Abrupt shifts in tense (reflecting Hebrew narrative tense logic)

Bivin’s analysis of Luke 9:51–56 shows a high density of such features, which he argues indicates “translation Greek”.

Special Luke

LukePrimacy.com notes that Special Luke—material with no parallel in Matthew or Mark -contains the strongest Semitic influence.

This includes:

- The infancy narratives

- Parables unique to Luke (Good Samaritan, Prodigal Son, etc.)

- Travel narrative sections

Scholars argue this suggests Luke is drawing on Semitic sources, possibly Hebrew.

A Gentile Lukan Author?

What is particularly interesting about the Semitic quality of the texts in Luke’s Greek is that the author of Luke (cast based on what we know of his namesake) reads more smoothly to Semitic readers than does Mark. It’s possible, of course, that this author, if in fact he was the Gentile Luke mentioned in Paul’s epistles, spent enough time with Paul and his fellow workers to pick up on the Hebraic patterns of thought and speech such that he could reproduce them in his Greek text. Or, our Lukan author may have had available Hebraically phrased source(s), possibly even in Hebrew, consisting of at least the 42 pericopes that he shared with Matthew’s author and Gospel. But, it is also possible that Luke’s author was a Jew who already knew and had facility with these Hebraisms. Either way, the resulting Greek does not read as if it were written by a gentile unfamiliar with Hebraisms.

The Issue of the Order of Events

It is indeed fascinating that of the Double Tradition pericopes shared only by Luke and Matthew, 18 of those 42 pericopes are essentially verbally identical. However, with one or two exceptions, they are not presented in the same pericope order in Matthew and Luke.

As noted, there are 77 pericopes shared by Matthew, Mark, and Luke (the “triple tradition”). These have a common order of presentation in all three gospels.

To repeat, Luke and Matthew share a common story order where Mark is present, but differ verbally with each other on their treatment of Markan pericope. Yet they are able to agree closely with each other in verbal matters when transcribing their non-Markan parallels. Significantly, they disagree in pericope order for these non-Markan pericopes. The question this raises is: “Where did this pericope order originate?”

Proposed Solution

Seeing that Matthew had preserved a few of the awkward renderings of Mark, Lindsey reasoned that, given Matthew’s otherwise extremely Hebraic Greek in the vast majority of cases, that Matthew’s author must have had Mark as a source from which to copy and replicate even its awkwardness (in the few cases where he did), and another source whose Greek phraseology of Hebraisms was more polished. So that left Luke as unadulterated by Mark and so, theoretically the first to be written.

But where did Luke get his non-Markan material? There are a couple of theories.

Dr. Stephen Notley points out that the Lukan material had the best grasp of the historical geography of Palestine. For example, Luke refers to the body of fresh water in the Galilee by the name by which it was known in the first century – Gennesar – whereas the other Gospel authors use the later (and thoroughly Christian-era term) “Sea of Galilee”. In Jesus’ day it wasn’t referred to by the romanticized term “sea”. It was simply a freshwater lake.

There is also literary evidence (Living Footnotes – LUUK VAN DE WEGHE) that Luke’s author spent time in the land in the later first century speaking with those who knew the Apostles and their stories in composing his version. (Of course, he would have had to have had access to eyewitness stories to even presume to author Acts.) The most pertinent such testimony is the author’s own in Lk 1:1-4

1Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, 2 just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word have delivered them to us, 3it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, 4that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught.

But, in addition to this first-hand information, it appears that Luke worked from two related Greek documents, as depicted in the following figure.

“A” in the figure stands for “Anthology” and is thought to have been a collection of the sayings and acts of Jesus (not unlike “Q”). “R” stands for “Reconstruction” and is a reorganization of the “A” material into a sequence (if not a precise chronology), which we might refer to as “proto-Luke” (see B.H. Streeter[vi]). Both were Greek but stemmed, apparently, from Hebrew predecessors. For a highly technical defense of the necessary existence of “R” (rather than the author’s reliance on the Septuagint for the rendering of Hebraic phrases in Greek) in analyzing Luke (and Acts), see Buth and Notleyiv.

The postulated existence of the Anthology also provides the explanation for why Matthew and Luke agree with each other’s words in the pericopes they share that are not found in Mark (42, of which 18 are virtually identical), but not in the pericope order present in the Reconstruction, known only to Luke. If Matthew’s author knew Luke at all, for his own reasons he elected to relate their common material in a different order than Luke.

Which Gospel Was First, And Does it Matter?

The “Markan Priority” Assumption

As we noted at the top, the consensus assumption from the 19th to the 21st centuries as to the sequence of Gospel authorship has been that Mark wrote first, was then copied by Matthew and Luke who both supplemented their material from a theoretical source called “Q” which contained sayings and scenes of Jesus’s life that they copied from, but which was apparently unknown to Mark. Why is this scenario believed to be accurate?

Mark is Shorter

First, non-specialists can point out that Mark is shorter in length than either Matthew or Luke in terms of word count (roughly 14,500 vs Matthew’s 22,930 and Luke’s 24,860). So, the reigning presumption is that earlier literary works are expanded by later literary works as additional content and details are added. So, they’re longer, not shorter. By this “blunt object” analysis, Mark has to be the first.

In point of fact, if you analyze the stories/scenes presented in Mark and compare the treatment of those same stories/scenes that are replicated in Matthew and Luke, Mark is by far the most verbose source. So “long” vs “short” book length is too coarse a measure for drawing conclusions about the sequence of the Synoptics, and certainly for locating them within a chronology.

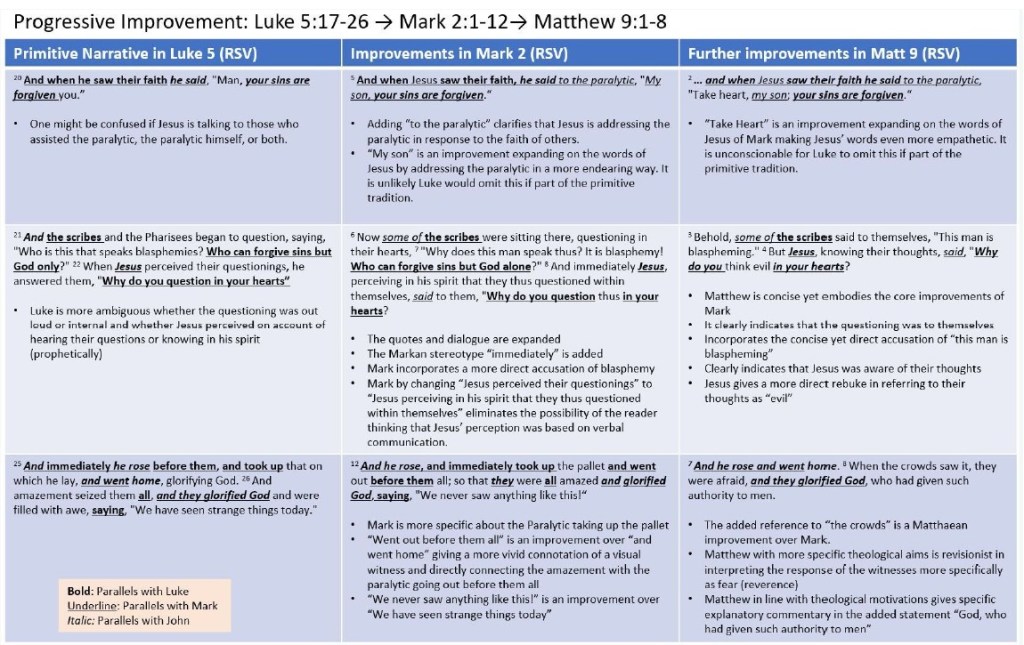

Scholars note, importantly, that for the triple tradition material in the Synoptics, Luke’s treatment is nearly always more primitive than the other two, indicating that they used Luke’s kernel as the base from which they elaborated. The following figure[vii] contains an example of that elaboration.

Second, the “Q” source hypothesis was an invention (of the early 19th century) that answered the question as to why Matthew and Luke “knew more” of the history of Jesus’s ministry than the author of Mark did, supposedly its “earliest eyewitness”[viii]. To be fair, the Q hypothesis is a solution to the textual/historical poverty of Mark vis-à-vis Matthew and Luke. But that’s all it is – a hypothesis, and one to address a presumed (not a proven) hypothesis of Markan priority.

What if Luke Was Written First?

What difference would “Lukan Priority” mean to our interpretation of the Gospels, if any? How, if at all, would it affect our understanding of Jesus? And, how would it affect our understanding of the theology of early believers in the nascent Church?

Technical and Literary Impacts

As with historical literature in general, a text written closer in time to the events it relates provides a higher degree of confidence in its accuracy than do later texts addressing the same time period. While we haven’t really speculated on the timing of the authorship of the Gospels, certainly their sequence of authorship is related to their relative dating. Consequently, the normal reaction to Lukan priority would be to consider the Lukan account more authoritative than has been assumed by scholars to date.

Luke’s text offers one possible piece of historical data that could help us date it. Its opening verses are addressed to “most excellent Theophilus” (v3). It is speculated that this Theophilus was the High Priest from 37 to 41 AD, as recorded by Josephus (grandson of Annas, brother-in-law of Caiaphas). The address “most excellent” was used in addressing high ranking religious and civil officials. The author also addresses this same Theophilus in Acts 1:1.

Theophilus the High Priest had a granddaughter, Joanna (Yohanah), who may also be the Joanna the author mentions later in Lk 8:3 and 24:10, who was clearly a follower of Jesus. In other words, our author of Luke/Acts may have had a close relationship with the family of Theophilus, causing him to testify the story of Jesus to them, in which one of its members played a significant role.

We know that this Theophilus was dead by 67 AD. So, our author would have had to have written to him prior to that date, placing Luke if not first in the sequence, at least early relative to current NT dating theories.

More Representative of Early Christian Narrative and Belief

If Luke was written first, there are some fascinating observations we can make about the earliest Christian beliefs vs how those developed in the early church as reflected first in Mark, and then Matthew.

Eschatology and Ecclesiology

In his treatment of the Olivet Discourse, Luke takes a very pragmatic view of the coming threat that Jesus describes (Luke 21). In particular, rather than use end-of-the-age language to describe the attack of Jerusalem by the Romans (70 AD), Luke has Jesus simply say: Lk 21:20-24

20“But when you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, then know that its desolation has come near. 21Then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains, and let those who are inside the city depart, and let not those who are out in the country enter it, 22for these are days of vengeance, to fulfill all that is written. 23 Alas for women who are pregnant and for those who are nursing infants in those days! For there will be great distress upon the earth and wrath against this people. 24They will fall by the edge of the sword and be led captive among all nations, and Jerusalem will be trampled underfoot by the Gentiles, until the times of the Gentiles are fulfilled.

This is pretty clearly a prophecy of an attack, battle, and catastrophic defeat of the Jews by a human army. Compare this with Mk 13:14-20

14“But when you see the abomination of desolation standing where he ought not to be ( let the reader understand), then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains. 15 Let the one who is on the housetop not go down, nor enter his house, to take anything out, 16and let the one who is in the field not turn back to take his cloak. 17And alas for women who are pregnant and for those who are nursing infants in those days! 18Pray that it may not happen in winter. 19For in those days there will be such tribulation as has not been from the beginning of the creation that God created until now, and never will be. 20And if the Lord had not cut short the days, no human being would be saved. But for the sake of the elect, whom he chose, he shortened the days.

Luke doesn’t invoke the kind of eschatological language that Mark does, who is perhaps seeking to emulate the language of the prophets. Luke’s interest seems to be communicating the gist of Jesus’s warning in clear terms: When you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, get out; it’s going to be made desolate; flee to the mountains; people will be slain by the sword, and Jerusalem trampled underfoot.

For his part, the author of Matthew makes use of much of Mark’s language, but adds an ecclesial spin, highlighting the impact on the church/community of believers (e.g., Mt 24:13, the parables of preparedness, “the elect” language – Mt 24:22, Mt 24:24, Mt 24:31).

Interpretation of Jesus’s Death

A particularly fascinating variation is found in the language used in describing Jesus’s death.

Unlike the later authors, Luke’s author never uses their typical salvation language in his gospel. For example, he never mentions personal redemption in the context of Christ’s death. Nor does he use the terms “propitiation”, “atonement”, “cleanse”, or “reconciliation”.

As for “redemption” as a product of the crucifixion, Luke’s only mention of the concept is the conversation of the men on the road to Emmaus – that they had hoped Jesus was the one “to redeem Israel”.

He does have Jesus speak the word “forgive”/”forgiveness” (Lk 23:34, Lk 24:47), but he doesn’t narrate it in his own words. Similarly, he has Jesus speak of “repentance for the forgiveness of sins”, but otherwise doesn’t mention “repent” or ”repentance”.

As for “save”/”salvation”, again Luke’s author doesn’t use the term other than as spoken by (Lk 7:50, 19:10), or of Jesus (Lk 1-2 infancy narratives where Zechariah prays a prophecy in which “we should be saved from our enemies” in 1:71).

Luke attributes no soteriological character to Jesus’s death, unlike the others. This would seem to indicate that the development of this doctrine within the church was a later development. To Luke, Jesus’s death was that of an innocent martyr (as in the trial narrative). He emphasizes Jesus’s calmness and trust in the Father throughout his passion narrative, starting in Gethsemane, contrasting with Mark’s darker apocalypticism. Luke uses the conversation of Jesus with the thief on the cross to introduce the idea that Jesus Himself has opened “paradise” to sinners.

Perhaps most significantly, Luke’s narrative emphasizes God’s mercy toward sinners and enemies (Jesus asking Him to forgive his executioners while on the cross). We find almost nothing of the later doctrine of sacrificial atonement – that “Jesus died for our sins”. Rather, Luke would have us understand that Jesus was the innocent, righteous martyr who perfectly presented God’s character, love, and healing to His people. And who was murdered (by us) because of it.

What Luke documents more extensively than the others is Jesus’s post-resurrection activities. It’s Luke who tells the story of Jesus walking with His mourners on the trip to Emmaus. Luke emphasizes the apparently bodily nature of Jesus in His resurrected form in Luke 24:36-49, showing the disciples the holes in his hands and feet, eating fish with them, etc.

The author of Luke records Jesus’s Ascension from the Mt. of Olives (Lk 24:50-53) and then goes on to relate other post-resurrection interactions with Him in the book of Acts.

So it seems clear that, whatever else the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus meant to the later gospel writers and the eventual Church doctrines that resulted from them, to the author of Luke, it meant that God had triumphed over death through Jesus as His Son.

Conclusions

The arguments, both literary and textual, for Lukan Priority have been thoroughly documented and researched. (The sites lukanpriority.com, JerusalemPerspective.com, and LukePrimacy.com are rich sources of the argument for this case.) To me, they seem persuasive. On the other hand, I haven’t researched the technical arguments for Markan Priority to nearly the same extent. They may present a persuasive case as well.

I believe the most compelling of the arguments for Lukan Priority is Luke’s more primitive language in describing either the triple tradition or double tradition pericopes than its later, more elaborated Synoptics.

The unique feature of the Jerusalem School Hypothesis is the postulated existence of, and use by Luke of, the Reconstruction. Its Anthology is the functional equivalent of the Markan Priority’s “Q” – a collection of Jesus’s sayings and acts that Luke and Matthew knew, but that Mark did not. “R”, however, adds a sequence to these events which, whether correct historically or not, acts to differentiate Luke from Matthew for those pericopes not shared with Mark. How “R” later became lost to Matthew after its use by Luke, and why Matthew would ignore its implicit presence in the sequence of Luke’s texts is a mystery.

But for me, the biggest takeaway from this study is that the church initially, as represented in Luke’s Gospel, lacked a majority of what would later be enshrined as Church doctrines, from the Trinity to Christ’s sacrificial atonement. For the early church, it seems that Jesus’s perfect and righteous life, followed by his murder, which He forgave (Lk 23:34), was the perfect preamble to His resurrected manifestation. That death was defeated by God in Jesus seemed to be the headline, at least among His earliest followers.

[i] Some of my linked references are to the site JerusalemPerspective.com, which is a pay site ($60/year). So, if you are not a member but are interested in the Jerusalem School, you may want to join and gain access to the material which I have linked here.

[ii] Lindsey, Robert L., A New Approach to the Synoptic Gospels, JerusalemPerspective.com, Feb., 2014

[iii] Biven, David, Cataloging the Gospels’ Hebraisms: Part Two (Luke 9:51-56), JerusalemPerspective.com, Sept 26, 2010

[iv] Notley, R. Stephen, Non-Septuagintal Hebraisms in the Third Gospel: An Inconvenient Truth in The Language Environment of First Century Judaea Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels, Volume Two, Brill, 2014

[v] Validation of Luke’s Special Material – Semitisms in the Gospel of Luke, LukePrimacy.com

[vi] Streeter, B.H., Proto-Luke, Chapter VII of “The Four Gospels: A Study in Origins”, 1924

[vii] The Spurious Emergence of Markan Priority, LukanPriority.com

[viii] The actual dating of the Gospels is an ongoing debate. But there are many arguments from scholarly analysis today that place them far later than has been traditionally assumed – early to late 2nd century.