And How Do We Know?

Introduction

How old are the books of the Hebrew Bible, and why should we care? Since the Bible is likely the most influential book ever written, we deserve to know the truth of its composition and history.

Ronald Hendel and Jan Joosten have written a book that (mostly) claims to answer our question, entitled “How Old is the Hebrew Bible? A Linguistic, Historical, and Textual Study”[i]. We’ll see if it does that.

Not everyone agrees with the authors’ conclusions. We’ll look at some of these authors’ assertions and a representative colleague’s critical disagreements.

Background

The methodology of Hendel is from a field called historical linguistics. Its simple idea is that the way a language is written and spoken depends in great part on when it is written and spoken. We can see this phenomenon in our own English, and within our lifetimes. The English our grandparents used was significantly different than ours, let alone our children’s or grandchildren’s. We see the English of the King James Version (circa 1611 AD) of the Bible eventually diverging sufficiently from our contemporary vernacular, to require modernizing it, resulting in the New King James Version update. So, their premise is sound, or at least intuitive.

In addition to purely linguistic analysis, the authors employ Textual Criticism in comparing their preferred Masoretic Text with other both Biblical and extra-Biblical texts; cultural history (including the influence of outside cultures on Hebrew writing); epigraphic analysis from known inscriptions, etc. When the majority of these analyses lead to the same historical period conclusion for a particular text – a condition the authors term “consilience” — the probability of that text having been written in the indicated period increases.

Hendel and Joosten identify four grammar styles found in the biblical texts, which they equate with four historical periods, each younger than its successor:

Archaic Biblical Hebrew (ABH) – chronologically quite ancient, but also very limited within the Biblical corpus

Classical Biblical Hebrew (CBH) – typical of the Pentateuch and the former prophets through First Isaiah (Is 1-39).

Transitional Biblical Hebrew (TBH) – located somewhere around the Babylonian exile – 6th century BC and characterized by a roughly balanced mixture of CBH and LBH grammars.

Late Biblical Hebrew (LBH) – typical of what is assumed to be the latest phase (Persian period down through the Hasmonean) of Israel’s second Temple period.

These periods, identified by their predominant textual characteristics, are indistinct, only conceptually identifying periods when one or the other of their attendant grammars were in popular use. If any single book of the Hebrew Bible is analyzed it is found to contain a mixture of both CBH and LBH language (with perhaps an archaism). The authors conclude that the presence of portions of TBH and LBH passages in an otherwise CBH text simply indicates later editing by scribes for whom those later language patterns were more familiar.

The subject of linguistic analysis is incredibly technical and dense, making it quite opaque, full of jargon and symbology that isn’t useful to the layman. The layman must assume that the linguist scholars know their stuff and faithfully report its results. And Hendel shows every evidence of having a thorough command of his trade.

Linguistic Analysis

What features of a language/grammar does the linguist analyze? Here is an outline of some of the main features:

- Orthography (spelling)

- Different spellings over time: e.g. sin-to-shin change

- Later adoption of vowel characters (yod, vav, he) in consonant-only word spellings

- Paleography – the style of characters used in writing the text – paleo-Hebrew characters before Square or Block characters (6th century BC)

- Influence of surrounding cultures’ writings – the adoption of foreign words (“loan words”; from Assyrian, Persian [e.g. “ruler” – 8269. שַׂר śar], Greek; adoption of “high” language descriptions employing the ruling empire’s phraseology, thereby acknowledging that empire’s dominant status and influence, thus “elevating” the Hebrew passage.

- Syntax – some words fall out of use over time (e.g. “seer”) and are replaced by new words (e.g. “navi” – “prophet”). Some Hebrew verb form usages also change over time[ii].

- Literary style – Hebrew poetry, for example, predates any Hebrew narrative/descriptive texts (e.g. Song of Deborah, Song of Miriam/the Sea) – so-called “archaic” Hebrew. But not all poetry is early.

- Historical context –

- If in a text there are no references to items that did not come into being (e.g. place names, king’s names, the names of later gods, etc.) then it is likely that the text is written earlier than the advent of those items.

- Anachronisms – in a historical narrative, the presence of references to later realities (e.g. the reference to “Darics”, a Persian currency, in the description of donations to David’s temple — 1 Chr 29:7).

- Historical errors e.g. wrong Pharaoh name or king name or city name (e.g. “Beth-El” in place of “Luz”).

Dating a Text

As Hendel himself points out, “The distinction between CBH and LBH by itself does not yield more than a relative dating”.

So how do you make a relative chronology quantitative? You have to synchronize it with other extra-biblical text or physical evidence of known dating. Unfortunately, the only physical (epigraphic) inscriptions we have (the Siloam inscription, the Lachish “letters”, the inscription at Kuntillet Ajrud) in Israel are dated from the 8th to the 6th centuries BC. The properties of these inscriptions correspond linguistically with Hendel’s CBH genre. So, he locates CBH texts as approximately 8th century, but in any case, pre-exilic (i.e. preceding the Babylonian exile and destruction of the early 6th century).

Hendel anchors CBH in the 8th-7th centuries. He then (quite arbitrarily) selects the 6th century as the time of writing of those books that share a balance of CBH text and LBH texts – our TBH category. Why the 6th century? Or rather, why should all TBH texts have been written in the 6th century and only the 6th century? Other than the obvious fact that the 6th century follows the 8th and 7th, Hendel provides no clarifying explanation. Finally, he locates the predominantly LBH texts in the 5th-2nd centuries[iii] — the Persian, Greek, and Hasmonean periods — as these texts contain multiple references to loan words from these civilizations and historical references to the 2nd-century Maccabean revolt against the Seleucids, etc.

The following table contains a breakdown of which books/texts best fit in which linguistic period according to the author’s conclusions, augmented by notes from “Timeline of Biblical Composition”[iv].

| Period (Hendel’s Implied Dating) | Text | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Archaic Biblical Hebrew (ABH) (Pre-8th century) | Song of Deborah (Jdg 5) Song of Miriam (/the Sea) (Ex 15:20-21) | Possibly 10th century. |

| Classical Biblical Hebrew (CBH) (8th-7th centuries) | Pentateuch (excepting some poetry demonstrating Archaic elements. Also, some have argued the “P” source language is “later”.) (All of the “J”, “E”, & “D” sources.) Joshua Judges (except ch 5, above) 1-2 Samuel 1-2 Kings Hosea Amos Some early Psalm poetry | In this period, the material from sources “J” and “E” are combined into a single narrative, identified as “JE”. |

| Transitional Biblical Hebrew (TBH) (6th century) | “P” and “H” sources. Deutero-Isaiah (Is 40-66) Jeremiah Ezekiel Haggai Zechariah 1-8 Jonah Lamentations Job | “P” and “H” edit and add to the Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers texts of “JE”. “R”(edactor), integrates Pentateuch texts likely in the 5th century. |

| Late Biblical Hebrew (LBH) (5th-2nd centuries) | 1-2 Chronicles Daniel Ezra Nehemiah Malachi Late Psalms (e.g. 103,117, 119,124-5,133,144. Another 23 are suspected to be late.) Song of Songs Ecclesiastes Ruth Esther | |

| Not Classified | Joel Obadiah Micah Nahum Habakkuk Haggai Zechariah (9-14) Proverbs – A mix of all genres/periods. | Micah likely 8th century; Zephaniah, Nahum, Obadiah, Habakkuk likely 7th century; Haggai, Joel, Zechariah 9-14 likely 5th century. |

Problems With These Conclusions

Not every scholar in the field of Biblical textual analysis buys either Hendel’s methodology or his conclusions and resultant textual dating.

Konrad Schmid has written a paper[v] in which he raises concerns about the methods and conclusions of the author’s. His criticisms are not technical in the main, but merely logical. Here’s a summary.

Dating CBH

Schmid comments that the author’s dating of CBH texts to the 8th-7th centuries is based partially on the presence of its features found in 8th-7th century inscriptions in Israel (as mentioned earlier). There are no inscriptions that have been found that date either from before the 8th century or after the 7th. If we had inscriptions from these periods, would they demonstrate CBH features? If so, what rationale would we have for dating CBH in the 8th-7th centuries? Schmid complains that this dating for CBH simply shows a bias for early dating by the authors.

Dating the Narrative, Not the Text

Schmid also observes that CBH is assigned this pre-exilic time period by Hendel and Joosten because they fix the timing of TBH to the 6th (exilic) century. Being earlier (according to the authors), that makes CBH pre-exilic. Why is TBH deemed exilic? Because its narratives are dominated by subjects having to do with the exile, the destruction in the 6th century, and the remnant’s return, the majority of which occurred in the 6th century. But is the date of authorship the same as the events about which the author writes? Not in the case of the Exodus, according to these same authors.

Obviously, this conclusion has no credibility as there is no corroborating evidence to result in a date of authorship. The best we can say is that a text couldn’t have been written before the events it describes occurred. Of course, later edits of an earlier base text could pull that base text forward in time by tying it to later events from the time of the editor. In such a case, the base text would predate the added events, incorrectly dating the modified text later than its original base text.

CBH Reproduced by Late Authors/Editors

An obvious possibility is that skilled authors/editors, thoroughly knowledgeable in the intricate details of CBH linguistic structures, could simply reproduce them in their texts, perhaps centuries after they had essentially fallen out of common use. Why would they do this? Perhaps simply to venerate an earlier author or subject that wrote in, or was described in, that style. Hendel talks about the “style” and “register” of a text – its “tone”, if you will, being elevated above common vernacular by an author/editor. We can perhaps relate to such a motivation if we imagine a modern author or orator elevating his message by using a style of language that was common, say, among the founding fathers, or perhaps Abraham Lincoln: “Four score and seven years ago…”.

Hendel dismisses this possibility. He doesn’t say some authors/editors wouldn’t try to do so, only that they couldn’t pull it off without leaving telltale signs of their infacility with the CBH genre that his analysis would uncover.

Late “Modernizing”

A text classified as LBH due to its preponderance of LBH features could have been a rather comprehensive “updating” of a more ancient (CBH?) text to make it more accessible/readable to the editor’s generation. Hendel mentions evidence of this practice found in the Dead Sea Scrolls [iii].

Dating Texts Having No or Minimal CBH or LBH Features

There are (apparently) many books or ranges of texts that contain no or only minimal overt CBH or LBH features. How do we assign dates to these? They’re just conventional Biblical Hebrew that, without related external evidence, has no distinctive date. They could have been written (subject to the event-date constraint, discussed above) at any time.

Conclusion

This book, unfortunately, doesn’t answer the question its title poses. What it does do is posit a relative sequence of some of the Bible’s texts, while others are undifferentiated. As Hendel and Joosten document, there are distinctive features of most Biblical Hebrew texts that tend to locate them within a cohort of such texts – a preponderance of CBH features, the CBH cohort; a preponderance of LBH features, the LBH cohort; a balanced mix of each, the TBH cohort (the ABH cohort is quite specialized and tiny). But putting date boundaries on these cohorts is virtually impossible without other, external data.

Stepping back to look at the big picture of Biblical composition, we shouldn’t ignore the impact even these relative (and in some cases disputed) dates have on the traditionalist view. No scholars I am aware of, for example, claim the Exodus narrative was a product of the 12th or 14th century BC. We have no data that allows us to claim it as an eyewitness account.

But we should also keep in mind that even traditionalists had Moses authoring Genesis, whose narrative begins some 2,600 years before Moses is thought to have lived. So perhaps eyewitness credibility isn’t as important to the assumed veracity of a Biblical text as many believe.

However, hearing that the Exodus account was authored some 600-700 years after it is thought to have happened, compels us to treat it, and its companion Pentateuchal texts, differently than we would if they did claim eyewitness authority. Even allowing for the assembling of earlier written and oral narratives passed down through the generations in the writing of the Pentateuch’s stories, we are compelled to deal with these texts in terms of the history they describe as idealizations of whatever cultural memories the authors describe.

Why Should We Care?

In answering the question: “Why should we care?”, I can think of a couple of reasons. First, knowing the general period of a text’s authorship helps us interpret it in terms of the symbology and allusions it uses to express its narrative. Knowing that First Isaiah was written when the war drums of Assyria were beating helps me understand the context of, for example, the author’s Messianic digression in Isaiah 11. The author thought the end of his people was at hand – imminent. What do you pin your hopes on in that situation? For “Isaiah” it was that your God is going to redeem you and your people from total oblivion. This particular author apparently wasn’t recounting a centuries-past approaching apocalypse. He was living it, and profoundly grieved by it. And you can feel his dread and indignation against his people who brought it on themselves in his emotional words.

Secondly, knowing the relative “lateness” of some texts, like Chronicles, helps an interpreter identify discrepancies between it and the narrative of Kings it recounts in terms of later cultural and religious developments in Israel (so-called diachronic analysis), such as the Persian influences, and those associated with the priesthood. The two accounts are separated in time and religious/cultural development by 500 years or so.

Scholars of the Biblical text need to decide the extent to which they are persuaded by Hendel’s relative dating methodology and conclusions. For myself, I find that the effect of late editing, even wholesale “modernization” of a text, has the potential to completely obscure analysis of that text’s original authorship. This potential, plus the authors’ quite arbitrary dating of the texts that they identify as the TBH corpus, result in my viewing the authors’ work not as necessarily useless, but simply less credible than the authors’ opinion of it. What do you think?

[i] Hendel, Ronald, “How Old is the Hebrew Bible?”, and Joosten, Jan, Yale University Press, 2018

[ii] Penner, The Significance of the Biblical Hebrew Verb Forms,

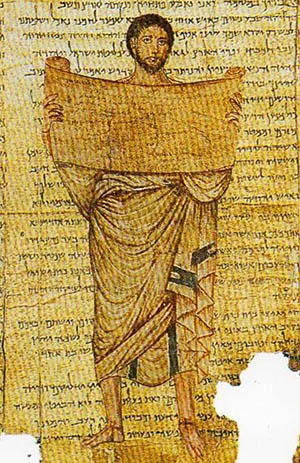

[iii] I thought it was interesting that Hendel points out that the Great Isaiah Scroll recovered from Qumran cave #1 (1QIsaa) is predominantly LBH, despite its chapters 1-39 being identified from the Masoretic Text as CBH. So apparently those chapters, in later copying, were grammatically updated by the copiest.

[iv] “Timeline of Biblical Composition”, usefulcharts.com

[v] Schmid, Konrad, “How Old is the Hebrew Bible? A Response to Ronald Hendel and Jan Joosten”, SBL Annual Meeting, November 23, 2019