Introduction

For centuries, the traditional, Christian interpretation of Jesus’ death has been that it was an atonement for the sins of those who would choose to “believe” and follow Him. This scenario portrayed a kind of cosmic cleansing for those who believed, though no one told us what that meant. A common assumption is that having one’s sins atoned for/forgiven is having them excused. For the record, not everyone completely bought the cosmic cleansing story, citing texts (e.g. Luke) that didn’t completely embrace the sacrificial atonement theme.

Recently, Dr. Jason Staples has proposed an alternative understanding of the crucifixion/resurrection, developed during 20 years of scholarly study of Paul’s writings and related extra-biblical material, that it was the inauguration of God’s promised New Covenant in which those who turn to God/Christ in trust receive God’s indwelt Spirit that transforms them to righteousness. They are transformed into people who have the capability to live their lives in faithful obedience to God’s will. Previously His will was only accessible to His people through His written Law and the words of His Prophets. Further, Staples even tells us what God’s purpose was in sending Jesus to Israel to inaugurate His New Covenant.

Staples agrees with Paul, who portrays the post-Christ dichotomy to his readers: living under the Law (in “the flesh”) vs to live “by the Spirit” (Ro 8:13-14), in which the Law is written on one’s heart, guiding the living of one’s life in obedience to God’s will (effectively cutting out the “middleman” of the written Law, and most religious leaders). This latter form of living is the message Staples picks up on and elaborates in his most recent book[i]. This mode of redemption is completely different than having “one’s sins forgiven”. The one indwelt by the Spirit can live righteously through the Spirit’s influence, while the one without the Spirit can only continue to live naturally – that is, unrighteously, but “forgiven” (whatever that word meant to its first-century hearers).

Describing Jesus’ Death

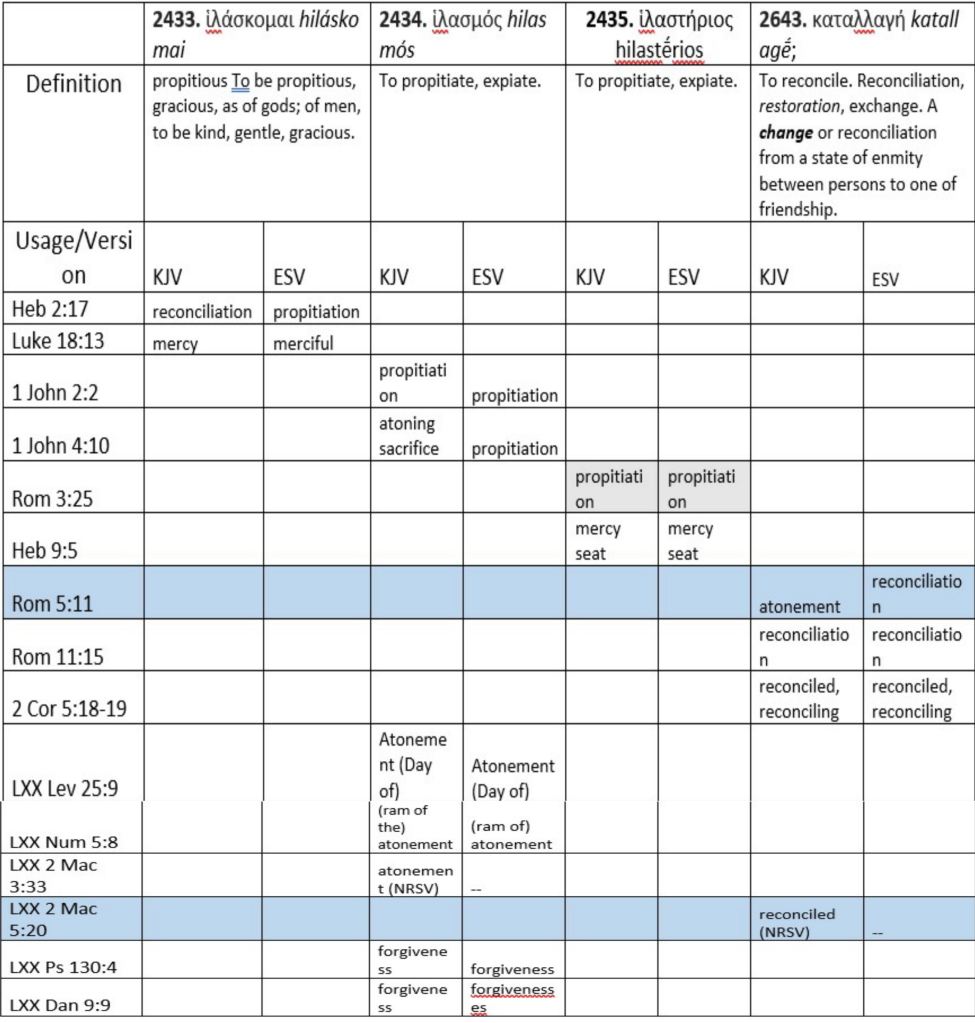

To develop a better understanding of the New Testament’s (NT) language used to characterize the effects of Jesus’ death and glorification, we need to identify the terms it uses and see how they are used. Unless we know what the authors of these characterizations meant by the words they use, we have little hope of understanding what they were trying to teach us with them.

If you don’t want to see all of the terminology details, don’t click on this text: just keep reading.

Our Layman’s Understanding

As Christians (and even others who just pay attention), we’re taught that we cannot live with God in our normal state of sinfulness. We need to get rid of that sin so that, well, we don’t get sent to that bad place when we die. We want God to judge us as “righteous” and so allow us to live with Him in His “heaven” forever. How does God intend to get that done?

A common understanding of the result of Jesus’ death is that it served to transfer all of our sin onto Him, which through his death and resurrection He not only “paid for”, but destroyed. So, the average Christian believes himself to be perpetually forgiven for whatever sin he may commit in the future due to Jesus’ “sacrifice” if he believes Christ was the Son of God, died “for my sins”, and was resurrected to God. This is the traditional understanding.

This expunging of our sin we usually refer to as “atonement”[ii] – Jesus’ death somehow compensating for or removing our sin. Rather than “atonement”, English translations like to use the term “propitiation” for the Greek term (ἱλασμός), which has the sense of “make amends for” – doing something to result in the removal, or at least the hiding, of our sin. The everyday meaning of the term is essentially “to appease”. So, the term is often (if only subconsciously) thought of as “paying God off” to amend one’s sin condition. In this model, the payer is Jesus.

The one other term commonly used in describing the effect of Jesus’ death is “reconciliation” – “to reconcile”. Paul was fond of this term and is the source of most of its usages in the NT.

Let’s look at the occurrences of these two word ideas both in the NT and in the Septuagint’s Greek version of the Hebrew Bible.

Let’s first examine what’s going on with the Hebrew term for Atonement (Num 5:8):

-

- כִּפֻּרִיםkippuriym: A masculine plural noun meaning atonement, the act of reconciliation, the Day of Atonement.

The image here is of the substitutionary sacrifice on Yom Kippur in which two goats were chosen; one for sacrifice and one for carrying Israel’s sins off to the wilderness (where goats didn’t last long alone) and so away from the people and God’s habitation in the Tabernacle/Temple.

To me, the fascinating thing here is that this dictionary[iii] conflates the idea of atonement (“making amends for”, usually by some offering) with “reconciliation”. We see usages of the Greek equivalent of this idea of “reconciliation” in the above table. Its definition is to repair the relationship between two persons by the one who abrogated that relationship changing so as to repair the source of the estrangement, thus reconciling the two and restoring their original relationship. (Notice that we’re the offending party – the one who abrogated our relationship with God by living unrighteously. So we’re the one who has to change, or be changed.)

Similarly, we have a bit of conflation going on with reconciliation. The verse in question says this (ESV): Ro 5:11

11More than that, we also rejoice in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have now received reconciliation.

Notice that the KJV translates this word (καταλλαγή) as “atonement”, not “reconciliation”. Additionally, we have the case of Heb 2:17, where here the KJV renders a completely different word (ἱλάσκομαι hiláskomai) as “reconciliation” while the ESV has the more standard “propitiation”.

These two English terms (and their Greek originals) seem, at least in these few cases, to be more or less interchangeable to the translators of those editions of the Bible. Should they be to us? Or is there some profound eschatological insight we’re ignoring by doing so?

What seems to be going on in the overlap of these two Greek terms is that they are two different aspects of the same action: ἱλασμός hilasmós is the means of atonement, while reconciliation, καταλλαγή katallagḗ, is its result: the one estranged having been changed to restore communion between the two parties.

This is a common understanding among Christians. The idea seems to be: “After Jesus atoned for my sins” (whatever that term actually meant in Jesus’ case)”, I’m reconciled to God.” So, these actions sound like two sides of the same coin – cause and effect. This is the classic thinking that has developed into the theory of substitutionary atonement.

I think it is fair to say that the early church didn’t have a well-formed testimony of what actually happened as a result of Jesus’ crucifixion until they negotiated an agreement hundreds of years after the fact (starting, perhaps, with Nicaea [325 AD] that pronounced what Jesus was, substantively, in language they could all at least vote for, if not wholeheartedly embrace).

And just so we don’t lose sight of the forest for the trees, we should notice that the Gospels virtually don’t mention any of these concepts (i.e., Lk 18:13, where ἱλασμός is actually rendered “merciful”). There is nothing from the authors of Matthew, Mark, or John (except John’s 1 Jn 2:2, 4:10).

The concept the Gospels do employ to describe the effect of Jesus’ death is the “forgiveness of sins”, where forgiveness is 859. ἀˊφεσις áphesis; gen. aphéseōs, fem. noun. from aphíēmi (863),

“to cause to stand away, to release one’s sins from the sinner. Forgiveness, remission”

The term in our translations is rendered “remission” as often as “forgiveness”. The following table documents the term’s NT usages:

| Uses of | 859 | ἀˊφεσις | áphesis | |

| Verse | KJV | ESV | ISV | ASV |

| Mt 26:28 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Mk 1:4 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Mk 3:29 | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiven | forgiveness |

| Lk 1:77 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Lk 3:3 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Lk 4:18 | deliverance, liberty | liberty, liberty | release, free | release, liberty |

| Lk 24:47 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Ac 2:38 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Ac 5:31 | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Ac 10:43 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Ac 13:38 | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Ac 26:18 | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiven | remission |

| Ep 1:7 | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiveness |

| Col 1:14 | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiveness | forgiveness |

| Heb 9:22 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

| Heb 10:18 | remission | forgiveness | forgiveness | remission |

In medical usage, someone is in a state of “remission” when their symptoms are diminished, possibly eliminated. The important similarity with the spiritual domain of Christ’s death is that those subject to His reconciliation/propitiation/remission still have their original disease, though they are thought of by God as if they didn’t.

It is also interesting that there is little sense of guilt conveyed by the term “remission” while there is by “forgiveness”. Our understanding of forgiveness is typically that it is a pardon by the one we offended, who, for all intents and purposes, forgets our offense. “Remission” sounds as if it is more of a “setting aside” of a condition (or at least its symptoms) we may be “victimized by”, like the cancer sufferer. This “setting aside” (or “setting apart from”) is, in fact, the base definition of ἀˊφεσις áphesis.

The use of the term in the Septuagint is interesting. There, it refers substantially to gaining freedom, either in the event of the Jubilee year, where freedom was granted from slavery or financial debt, or other occasions in which God “freed” Israel from either their bondage or exile.

So possibly we, and our modern Bible translators, don’t actually have an accurate handle on the action of ἀˊφεσις which Jesus’ death produced as attested throughout the NT? That is certainly possible[iv]. The modern Western concept of being freed from something seems somewhat at odds with the similarly modern Western idea of being forgiven for something.

Proposing Some Definitions

Our goal is to understand what Jesus’ death, resurrection, and glorification achieved as understood by the Gospel authors and Paul. Let me propose the following definitions of these terms (and some additional ones) as an aid in converting them from just “Bible words” to something meaningful and understandable.

Atonement/Propitiation (ἱλασμός hilasmós)

This is the performance of an action that makes amends for an offense against God by one who is penitent. This action can be characterized as appeasement, as was the model of Temple sacrifices in which it was thought that the offering of an animal’s life-blood (or other oblation) to God resulted in His appeasement concerning the penitent’s sin. (It was also preeminently believed to ritually cleanse the Temple precinct from the penitent’s moral impurity.) However, as noted earlier, the use of this term in the Gospels is limited to Luke 18:13 (“merciful”), not being otherwise mentioned in the NT until Paul (and, of course, John’s epistles). This action is often paired with the following, which it is seen as triggering:

Reconciliation (καταλλαγή katallagḗ)

The repair of a broken relationship by the one who caused the split, reforming himself/being changed so that the characteristic that had led to the estrangement no longer exists. Notice who’s going through the reform of his character/behavior – the offender. Think “the Prodigal Son” returning home. He changed his behavior to contrition and was restored by his father. As noted, this action is often thought of as a derivative of the preceding Propitiation/Atonement action.

The traditional sacrificial atonement view holds that Jesus’ death resulted in our sins being ‘forgiven’, by God. But there’s no change to us in that transaction. So, it is not at all clear how we can be considered to have been reconciled to God, since we have changed nothing to restore our relationship with Him.

Forgiveness/Remission (ἀˊφεσις áphesis)

Jesus Himself proclaims that the purpose of His death is the “forgiveness of sins”: Mt 26:28

28for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.

This may be the most widely misunderstood Greek term in the New Testament, IMHO. As we saw, its Bible dictionary meaning is “to cause to stand away, to release one’s sins from the sinner. Forgiveness, remission.” The NT authors, and Jesus Himself, repeatedly use this term to characterize an effect of Christ’s death. (Luke, in Acts 5:31, however, sees forgiveness [our sin being removed away from us] as the result of Christ’s glorification, not simply His death. But we never see it being described as the result of Christ’s resurrection, per se.)

But what did Jesus have in mind in making this statement? The traditional understanding is that by his sacrificial death, he pardoned us of our sins. But the question that raises is this: If you’re God, and to you everybody who trusted Christ is now, effectively, “sin-less”[v], why do you still need a New Covenant? Why, in fact, was it necessary for God to pour out His Spirit on those in Jerusalem on Pentecost if in looking at them He saw righteous sinlessness — people who believed in His crucified Son? Perhaps more revealing, if many of those now considered sinless due to Christ’s sacrifice still live unrighteously (i.e. committing sins), what good is that to God in seeking a righteous family?

It seems those forming the traditional view of Jesus’ death may not have paid adequate attention to God’s overarching goals. Of course, God did launch His New Covenant (on Pentecost). It appears that He wasn’t so much interested in pardoning sins (though that may be part of it) as He was in gifting His Spirit to prevent sins in His faithful, so enabling them to live righteously. It is not unreasonable to conclude that in saying He was to “forgive” sins what Jesus was actually saying was that after His death He would send God’s Sprit into those who trusted Him (Jn 16:7) so that they would be defended against sin, thus causing their potential sin to “stand away” from them.

Justification (1347. δικαίωσις dikaíōsis; gen. dikai-ṓseōs, from dikaióō (1344), to justify.)

In the NT context, justification is the result of God pronouncing that one is “righteous”, “just”, resulting from his commitment to fidelity to Christ/God. We don’t typically think of it as a gift purveyed by the crucifixion, but Paul specifically ties this conferring of justness to Christ’s death: Ro 3:24-25

24 and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, 25 whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith.

25 who was delivered up for our trespasses and raised for our justification. (Notice: Not just death, but also resurrection.)

Ro 5:18

18Therefore, as one trespass led to condemnation for all men, so one act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all men.

One is not made “righteous” or “just” by this pronouncement. But his status with God is changed. The one declared righteous becomes effectively an adopted child of God. Justification, according to the NT texts, results from our trust in Christ as our Lord (not simply our Savior), and our sincere desire to change from our old life to a new life “in” Christ/God. The Gospels don’t mention this idea of justification by God through fidelity to Christ, only Paul. (They were evangelizing, not “theologizing”, except, perhaps, John.)

Salvation (3085. λύτρωσις lútrōsis; gen. lutrṓseōs, fem. noun from lutróō (3084), to release on receipt of a ransom)

This term is all about being freed from physical or spiritual danger (death) (often characterized in the Hebrew Bible as from a “tight” or “narrow” place) through the action of a redeemer – one who redeems you to your rightful owner – God. The one saved is sometimes said to have been “delivered” (3860. παραδίδωμι paradídōmi; fut. paradṓsō, from pará (3844), to the side of, over to, and dídōmi (1325), to give. To deliver over or up to the power of someone.)

Cleanse (2511. καθαρίζω katharízō; fut. katharísō, in the Attic kathariṓ (Heb 9:14), from katharós (2513), pure. To cleanse, free from filth)

The image of cleansing associated with Jesus’ death is applied very rarely in the NT. We see it in 1 Jn 1:7, Titus 2:14, 1 Cor 6:11 and two places in Hebrews (as we might expect): Heb 1:3, and 9:13-14. It is surprising that, if the NT authors were convinced of the accuracy of the metaphor between Christ’s death and the sacrificial deaths of the Temple, they would refer to this most prevalent of images associated with Temple sacrifice so sparingly.

Language Takeaways

We’ve looked at many of the terms used to describe the effects of Jesus’ death, resurrection, and glorification. Many of their meanings aren’t intuitive to the modern, Western English speaker. In such cases, the reader tends to apply his own definition, sometimes drawing a completely unfounded conclusion about what the NT author said.

What we see in the usage of these terms is a variety of different translations to English terms about which we have some intuition. But this varied translation and usage also leads to some confusion as to just what meaning the NT author intended the Greek term to convey.

For example, the term ἱλάσκομαι (hiláskomai) we see being rendered as: propitiation, mercy, and reconciliation, terms having significantly different English definitions. The term ἱλασμός (hilasmós) gets rendered as propitiation, atonement, and forgiveness (LXX). And the term καταλλαγή (katallagḗ) also gets rendered as atonement, but more commonly reconciliation.

The Gospels’ term ἀˊφεσις (áphesis) gets rendered as forgive(ness), release, free, liberty, and more commonly remission.

The term δικαίωσις (dikaíōsis) has a consistent rendering of justification, or ‘declare righteous’. But Paul introduces ambiguity by mixing it in with propitiation and redemption (as equals) in his handling of it (Ro 3:24-25), making it just one of several aspects, or effects (redemption, propitiation, life), of Christ’s death and resurrection.

For those of you accomplished in Koine Greek, you may see distinctions between these terms (some of which we’ve remarked on) that clearly differentiate one from the other, despite their mixed use. But for the layman trying to understand what happens to the person who turns from his current life to a life of fidelity to Christ, all of these things seem to be aspects of the event, and simultaneously. So that’s the model I propose we adopt in the following discussions[vi]. As Jesus breaks it down (Mk 1:15), what we do is “repent and believe” (where, I have argued, ‘believe’ is better rendered ‘place one’s trust in’).

Traditional Models of Christian Redemption

A prototypical model of modern, protestant Christian redemption goes something like this:

- Christ’s death was to “forgive” our sins (acts violating God’s will), by which is understood to “excuse” our sins (not simply put away or remit).

- Those who repent and “believe” that Christ died to save us are, as a result, “justified” by that faith before God. Some think this step is taken by praying for Jesus to “come into my life/heart” or similar. Such schemes seem to go out of their way to downplay sincere repentance – the rejection of one’s life apart from God and turning to God in ultimate trust and fidelity, and substitute something more like an apology (“I was wrong. Forgive me.”). It’s likely nobody ever explained to these folks what repentance means.

- Somewhere along the way, the convert will typically slip into a water baptism during which he will publicly profess his intellectual agreement that Jesus is the Son of God Who died for his sins and rose from the dead.

- Having “believed” and perhaps prayed a prayer, the “convert” believes his sins have been forgiven him for all time and that he will be welcomed into God’s heaven when he dies. That is the common expectation, whether or not he ever actually serves, or even thinks about, Christ during the rest of his life.

- An unmistakable feature of this traditional view is that its point of view is “me”, and its field of view is largely the past – “my sins I have committed are forgiven”. Of course, people of this view also believe that all of their future sins will similarly be forgiven. But there’s no sense of an imminent new life – one in God’s presence. There’s no sense of a purposeful future. Its sense is that you have been declared to be one of God’s children, so when you die, you’ll go to heaven.

What about our language of the effects of Jesus’ death in this portrayal of Christian redemption? Could this person’s sins have been propitiated? There doesn’t seem to be any reason they couldn’t have been. Could this person have been reconciled to God? This seems unlikely.

As we saw in looking at reconciliation, it is the one who is out of relationship with the other whose role it is to change to repair their broken relationship. This hypothetical person, so far as we know, has not changed. He has agreed with some statements. But he is essentially the same person as before, just one who has professed his intellectual agreement that Jesus is Lord. What about his former sins being set apart from him by his “belief” in Christ – i.e., his forgiveness? Does his life show any evidence of having been separated from his former sins – any expressed gratitude or thankfulness? Is he different? In too many cases, he is not.

Its and His problem seems to be that it leaves out the predicate to the whole process – the repentance for his former life apart from God and desire to live God’s life[vii]. He hasn’t actually committed to that. He likely recited some one-liners that were not the desire of his heart, as will likely be proven out by his subsequent life being, for all intents and purposes, little changed from his former life.

Is this what becoming a follower of Christ looks like? Is this what Jesus Himself had in mind? All of us should be sobered when we read Him proclaim: Mt 7:23

23 And then will I declare to them, ‘I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness.’

And far more important, do these actions by potential converts sound like they’ve experienced the change God prophesied He would create through His New Covenant?

The Paradigm of Redemption/Salvation by Transformation

A vastly different model of redemption has been revealed in the texts of the NT (mainly Paul) by Dr. Jason Staples in his books and recent videos.

Staples’s revelation is based on a few key points:

- The desire of the potential convert to change (repent from, redeem) his life from its former separation from God to a life of dedicated ‘fidelity’ (Staples’s word, used to replace our neutered “faith”) to Christ is sincere; heartfelt. It is not simply an affirmation that Jesus was Who He said He was. This is the heart of the matter.

- The popular Western (protestant) model of conversion that we looked at briefly results in the majority of its cases being unchanged people – people who continue to live apart from God (but who nevertheless think they have been “forgiven” [read “excused”] for doing so.) Crucially, this doesn’t solve God’s problem of His created humanity living apart from Him – out of communion with Him. His purpose in creation was to be glorified by His human family (Is 43:7). He can’t do so if that ‘family’ remains separated from Him in their unrighteousness and unrepentance about it.

- The entire purpose of God’s New Covenant (Dt 30:6, Jer 31:31-34, Ezk 36:24-28, Ezk 37:21-23, Is 11:11-12, Joel 2:28) is the changing of the hearts of His people so that they will love Him, be naturally obedient to His will, and know Him.

- Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection were not only a fulfillment of the law (in that His life was sinless according to that law, and so also a fulfillment of Israel’s purpose as God’s people), but also the event triggering the inauguration of God’s New Covenant, which occurred 50 days after His resurrection.

- In sending Jesus and initiating His New Covenant God was being faithful not only to His promises to the kingdoms of Judah and Israel to restore and reunify them (Eze 37: 1-17), but also to Abraham that through his progeny “shall all the nations of the earth be blessed” (Ge 22:18). The problem this created for many Jews is that it necessarily (due to the dispersion of the tribes of Israel into Gentile nations) included Gentiles, creating a stumbling block for many even of the early church. (We can see even the disciples wrestling with this revelation in Acts 11. They didn’t understand it, but they knew it was true.)

- The motive force behind this change of God’s people, their transformation, was (and is) the indwelling within them of God’s Spirit. He is the heart changer (Eze 36:36-27). He brings the knowledge of God (1 Co 2:10-12). And He brings the love of God (Gal 5:22-23). The Spirit is granted to the supplicant after he has sincerely repented (point 1) and entrusted himself to God.

- The one transformed by the Spirit possesses the ability to live his life in accordance with God’s will – “to live your life as Christ would live your life if He were you”[viii]. Though he can on occasion thwart the leading of the Spirit, he nevertheless is normally led to desire to and act in accord with the Spirit (Ro 8:13). This results in the Christ-follower living a life that is viewed by God as righteous. This is God’s overarching will for us – to live for and with Him in righteousness. In fact, this is what the entire Bible is about.

- Everyone will be judged on the last day – sheep and goats, pastors and child traffickers, and everyone in between. The one who has been equipped to desire and lead a righteous life, and who has not rejected that Spirit, will be found righteous on that day. Those who have not been led by the Spirit in their life will be found unrighteous (Mt 25:31-33).

- Significantly, this view of salvation is all forward-looking. It promises a new life being lived out in obedience to God, and so being deemed “righteous”. The indwelt Spirit will resist any temptation to live outside God’s will, making it possible to live faithfully.

Given our brief characterization of modern, mostly evangelical “conversion” doctrine, and this latter doctrine espoused by Staples, let’s compare and contrast a bit and see through which understanding God’s promises seem to be fulfilled[ix].

Contrasting Conversions

The Bible presents several expectations of God for His people, which we shall look at. In doing so, we’ll label the conventional approach as “conventional” or “traditional”, and the Staples-articulated approach as “transformation” or “NC” for New Covenant.

Glorification of God (Is 43:7)

It is quite easy to see how God might be glorified by creating millions of little “Christs” through transformation. It is not easy to see how he would be glorified by the conventional model if the majority of its clients remain unchanged from their apart-from-God lives.

Establishing a Family

Israel, the nation, was originally referred to by God as His “son, My firstborn” (Ex 4:22). His appeal to them to return to Him from their estrangement and then exile also uses the metaphor of father and children (Jer 3:19-22). As the story develops, we read of those of Israel who chose to return to Him (not just to the land), and those who didn’t, and we increasingly see God distinguishing between the two – the faithful and the unfaithful.

(Click here to see an extremely clear example of the dichotomy of faithful/unfaithful in Isaiah 65.)

[65:1] I was ready to be found by those who did not seek me. I said, “Here I am, here I am,” to a nation that was not called by my name. [2] I spread out my hands all the day to a rebellious people, who walk in a way that is not good, following their own devices; [3] a people who provoke me to my face continually, sacrificing in gardens and making offerings on bricks; [4] who sit in tombs, and spend the night in secret places; who eat pig’s flesh, and broth of tainted meat is in their vessels; [5] who say, “Keep to yourself, do not come near me, for I am too holy for you.” These are a smoke in my nostrils, a fire that burns all the day. [6] Behold, it is written before me: “I will not keep silent, but I will repay; I will indeed repay into their lap [7] both your iniquities and your fathers’ iniquities together, says the LORD; because they made offerings on the mountains and insulted me on the hills, I will measure into their lap payment for their former deeds.”

[8] Thus says the LORD: “As the new wine is found in the cluster, and they say, ‘Do not destroy it, for there is a blessing in it,’ so I will do for my servants’ sake, and not destroy them all. [9] I will bring forth offspring from Jacob, and from Judah possessors of my mountains; my chosen shall possess it, and my servants shall dwell there. [10] Sharon shall become a pasture for flocks, and the Valley of Achor a place for herds to lie down, for my people who have sought me. [11] But you who forsake the LORD, ready to be sought by those who did not ask for me; who forget my holy mountain, who set a table for Fortune and fill cups of mixed wine for Destiny, [12] I will destine you to the sword, and all of you shall bow down to the slaughter, because, when I called, you did not answer; when I spoke, you did not listen, but you did what was evil in my eyes and chose what I did not delight in.” [13] Therefore thus says the Lord GOD: “Behold, my servants shall eat, but you shall be hungry; behold, my servants shall drink, but you shall be thirsty; behold, my servants shall rejoice, but you shall be put to shame; [14] behold, my servants shall sing for gladness of heart, but you shall cry out for pain of heart and shall wail for breaking of spirit. [15] You shall leave your name to my chosen for a curse, and the Lord GOD will put you to death, but his servants he will call by another name, (see Is 62:4) [16] So that he who blesses himself in the land shall bless himself by the God of truth, and he who takes an oath in the land shall swear by the God of truth; because the former troubles are forgotten and are hidden from my eyes.

It seems quite clear that God’s foremost desire for his humanity was that they (or a substantial portion of them) would choose to live with and for Him in accordance with His will, as His faithful children. We’re drawn to His grand love instruction in Deuteronomy, the Shema: Dt 6:4-5

4“Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one. 5You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might.

As late as the early 1st century AD, however, that had not yet happened.

So, which one of our interpretations of “conversion” seems better designed to yield people faithful to God who love Him? I don’t think there is much debate. People who are transformed by God’s Spirit are clearly better-equipped members of God’s family to love than those who continue in their worldly affectations.

Redemption of “Israel”

Here we’re talking about the process of both the southern tribes of Judah and the more elusive northern tribes of Israel/Ephraim, returning not only to their God (as Jesus said [Mt 15], “24 He answered, ‘I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.”), but to each other as a single nation/assembly (Eze 37:1-17).

Neither these prophecies nor the promise to Abraham (Ge 22:18) had, at the turn of the millennia, been fulfilled.

So, which of our methods of “conversion” better (or at all) attempts to accomplish these goals of God? I would like to suggest that the modern church doesn’t even understand this question. As far as I am aware, in the history of Church, it has never acknowledged the goal of God to regather His newly faithful descendants of Jacob to Himself, let alone to be part of its mission to facilitate that regathering.

Yet we have Jesus proclaiming that regathering the lost of Israel to their God was why He was here (Mt 15:24)!

So, you might ask, “What does Christianity have to do with this regathering goal of God’s?” This is the question that Staples answers in his first book[x]. In a nutshell, the northern tribes in particular (but also the non-returnees from the Babylonian exile of the southern tribes) had been assimilated into the cultures into which they had been exiled, so becoming, for all intents and purposes, Gentiles. Paul’s mission, then, to evangelize Gentiles throughout the regions into which these exiles had been sent hundreds of years earlier, suddenly made sense (though, as noted, not to the Disciples). God was gathering the kin of Jacob who sought to live faithfully to Israel’s God back to Himself through the message of His Christ.

So once again we ask, “Which model of conversion” creates a more devoted Christ-follower (or God-fearer, if you prefer)? Certainly, it would be the one where God Himself is the change agent and gatherer.

A Blessing to the Nations

The capstone of the whole plan of God, irrespective of whether it was His primary, secondary, or other goal, was His promise to Abraham to bless the nations through his progeny. Of course, the preaching of the Gospel of Christ has, since the beginning, resulted in sincere choices of its hearers to leave their former lives and turn in trust and commitment to live the life God wants for them. Those He has transformed through His Spirit. And it is this transformation that is the realization of that promised blessing.

Deconstructing the Gospel Message

At the risk of beating a dead horse (I have written about this a lot), the Gospel message has nothing to do with going to heaven when you die (and waiting around until you do). This is the Western heresy of the Reformation.

The Bible doesn’t give us enough information to decompose “conversion” into its constituent sub-events if, indeed, there are any. Based on some of the texts and word contexts we’ve looked at, it seems as likely as not that those words are all simply different ways to characterize a singular conversion event, the one orchestrated through God’s New Covenant of the Spirit.

And if we see all of these characterizations as just that – different ways to look at and describe the change that occurs in the one being transformed, what doctrine, what soteriology do we lose? I don’t think any. If anything, I think the soteriology emanating from this view of redemption makes far more sense. Seen from this perspective, the Christian conversion event can be, and is, characterized as:

- Justification – being seen as just/right and so a member of God’s family

- Certainly, the one indwelt by God’s Spirit He sees as “just”.

- Propitiation/Atonement – a subject’s act of making amends on behalf of its object

- The “amends” made in the convert; the change to him to being “led by the Spirit” from his being led by his sin nature, qualifies as an “atoning” change. Was Jesus’ death the “appeasement” enabling that change? I’m not sure we have to think of it as appeasement. But whether or not it had that connotation, it certainly inaugurated the pouring out of the Spirit that created the change.

- Forgiveness/Remission – an act of putting the sins of its object away from him, causing him to experience spiritual health.

- Here’s an interesting take on “forgiveness”. Recall its definition is to “cause to stand away”, speaking of our sins from us. This is precisely the role of the Spirit. The Spirit inhibits our propensity to sin and so causes sin to “stand away” from us, separated from us. Sin reduction (though not total elimination) is separating us from the sin we would otherwise engage in.

- Reconciliation – the change of the one being reconciled (which we should, no doubt, read as the indwelling in him of God’s Spirit) resulting in the restoration of right relationship between himself and his God.

- This is perhaps the clearest tie to our New Covenant transformation. Unquestionably, the Spirit is the agent that changes the nature of the convert from “fleshly” to righteous and so in a state of “reconciled” with God.

- Salvation – our spirit being released from imminent danger/death by a redeemer.

- This condition seems to be intimately related to our “forgiveness/remission” in that in acting as a sin defense mechanism to keep our (potential) sins away from us, we are released from the peril of what Paul called the “law of sin and death” (Ro 8:2). The one in whom the Spirit dwells who is as a consequence judged as righteous on the last day, is saved to eternal life with God.

This is the “packaged deal” that is carried out upon one’s conversion. Of course, this is not all of the effects that will ultimately occur. For example, it only marks the beginning of the convert’s lifelong transformation (2 Cor 3:18) into increasing Christlikeness, sanctification. There is also “glorification” (Ro 8:30), which I would argue we have insufficient information to even speak of.

Conclusions

Stepping back from this a bit, it seems that this kind of metamorphosis is not only what the prophets of Israel expected as they prophesied Israel’s regathering and restoration at the end of the age, but it should be unsurprising to us that this is what Jesus was describing with His metaphor of “the Kingdom of God” [xi]. What better way to characterize a transformed society in which God is its population’s King? This is the society of God’s Spirit in which God isn’t some remote ruler but a moment-by-moment guide.

Was Jesus’ death a “sacrificial offering” as is traditionally believed? Was it a “payment” for our sins? There is no question that the Temple sacrificial metaphor pervaded much of the early NT writings. In retrospect, it’s hard to see how it could not be for its Jewish authors, since it had been the core of their cultural life and so almost had to seep out into their narratives.

One could argue that Jesus’s murder was simply the acting out of the last instance of the ancient pattern of “Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you” (Lk 13:33-34). As such, it would have underscored the cursed destiny of the Jews if they remained separated from God’s Kingdom.

Or, was His life His offering, which He gave freely in seeking to return Judah and Israel to their God, and finally to call disciples from “all nations” (Mt 28:19)? Jesus was convinced that His life was His to give freely, Jn 10:17-18:

17 For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life that I may take it up again. 18 No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have authority to lay it down, and I have authority to take it up again. This charge I have received from my Father.”

This doesn’t sound like a lamb being led against its will to be slaughtered. And it surely doesn’t sound like God taking retribution on this Man to satisfy His wrath. Frankly, it sounds much closer to the Aqedah than to substitutionary slaughter — a challenge/test of faithfulness.

God sought a faithful family that loved Him and their neighbors. Jesus’s life was the ultimate exemplar of that faithfulness and love, even to death. At the very least, the example of Jesus’ life displayed to all the goal of their coming transformation by the Spirit.

God appears to have honored Jesus’ life by raising Him after “three days”. Was this resurrection, in fact, the cosmos-changing event that then triggered the outpouring of God’s Spirit into those who sought Him in their repentance? All of the historical evidence seems to point that way. Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear that His Disciples understood this cause-and-effect.

Despite all of the metaphorical ink that has been spilled developing the image of the “lamb of God” being led to the slaughter, etc., etc., maybe those sacrificial death images are just an incorrect model created by inaccurately invoking and applying the Temple sacrifice “template”. Maybe we should just take Jesus at His word rather than erecting a sacrificial atonement theology.

If we clearly understand Jesus’s role in inaugurating the New Covenant, we can recognize that causing our sins to “stand away” from us is accomplished by the working of God’s Spirit in us to enable us to live righteous lives. That’s the Gospel. Sadly, it seems that it has taken us 2,000 years to figure it out.

[i] Staples, Jason A. (“Staples”), “Paul and the Resurrection of Israel”, Cambridge Press, 2024

[ii] The word only appears in the following English usages: KJV – Rom 5:11; NIV Ro 3:25, Heb 2:17; NASB Ro 3:25, Heb 2:17; NLT Ro 3:25, Heb 2:17, Heb 9:5

[iii] The Complete Word Study Dictionary: Old Testament

[iv] The use of the term in extra-biblical literature focuses on the idea of release, as from moral or financial debt, from a legal obligation through amnesty or pardon, even of an athlete or horse being released from the starting gate in a race. And it is used in medical contexts (remission) just as today.

[v] The traditional view holds that God in looking at us effectively sees Jesus. No sin.

[vi] Others examining these terms have come to the same conclusion. See, e.g.: Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity Online

[vii] In my opinion, Christian churches shouldn’t have anything to do with soliciting “conversion” except possibly offering a baptismal venue after the fact. “Conversion” is 100% about the sincerity of the supplicant’s heart to live for God, and 0% about him praying a prayer, responding to an emotional alter call, or any other trapping of the modern Western “church”. However, after his conversion, the Church can and often does have a positive effect on the new convert in what is called his “discipleship”, but what is in practice simply an apprenticeship to a seasoned veteran of the Spirit-led life.

[viii] Willard, Dallas, “The Divine Conspiracy”,

[ix] Just to be clear, some that promote the traditional evangelical explanation of conversion do, in fact, continue on to say that the convert will be “given the Holy Spirit” (since it is the lion’s share of the doctrine of Christian conversion presented in the NT). They just don’t emphasize that it is that indwelt Spirit that is their salvation. Going to heaven still dominates their perspective.

[x] Staples, Jason A., “The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: A New Theory of People, Exile, and Israelite Identity:”, Cambridge University Press, 2021

[xi] McKnight, Scot, “Jesus and His Death : Historiography, the Historical Jesus, and Atonement Theory”, Baylor University Press, Oct 10, 2005