Introduction

The Exodus itinerary is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. We don’t know where virtually any of its stopping points were. At best we know something about what was there, and, rarely, how long they traveled to get there. And, of course, there’s the inertia of the traditional explanation (i.e. via Sinai’s St. Catherine’s) and its advocates more or less dominating the discussion (and generating quite emotional reactions to any proposed alternative).

Truth in advertising: I don’t subscribe to the most popular theories that have Israel crossing the Gulf of Aqaba either at Nuweiba or at its southern tip at the Straits of Tiran. This isn’t because I don’t think God could take them through those spots – He can do anything He wants – but rather because locations on the east side of Sinai don’t match the Bible’s plain narrative.

In researching what is known today about the Eastern Nile Delta from which they left, and features in the Sinai Peninsula, we should be able to construct a logical and plausible, if perhaps unconventional, itinerary to align with the authors of Exodus’ and Numbers’ (33) narrative. Famous last words.

What We Know

The Bible’s narration of the Exodus itinerary is found in essentially two books: Exodus (beginning in Ex 13), and Numbers, primarily in chapter 33. (Interestingly, the latter never mentions Horeb; only “Sinai” in Num 33:15.)

In addition, we have substantial topographical and hydrological analysis that has been produced in the last 60 years covering the Eastern Nile Delta, from which the Exodus began.

And then, of course, we have the endless speculation as to where, in fact, Horeb/ Mt. Sinai actually is. Nobody knows, nor is one candidate head and shoulders more likely than any other. The available data from the Biblical narratives simply don’t adequately pin it down, nor does archaeological evidence, yet.

Additionally, we need to remember that Moses had been called by God to lead the Exodus from a bush at the “Mountain of God” in or near Midian (NW Arabia), his home for forty years as a shepherd for his father-in-law Jethro. Given his interaction with God there and subsequently, in the ordeal of freeing Israel from Egyptian bondage, it is quite likely that he was preeminently interested in getting Israel back to that mountain, particularly after the Egyptian forces were consumed in the sea. He knew unequivocally that this (the release of Israel from Egypt) was God’s enterprise, for which he was God’s agent. So, delivering Israel to God’s presence at that mountain must have been his preeminent intent.

Key “Facts” the Narrative Presents to Help Us Draw Key Conclusions About Locations

Where Israel Started Their Exodus

The first fact we are presented is the location of Israel in Egypt. We’re told that Moses continually visited Pharaoh to plead his case for Israel’s release. Moses was with the Israelites who, we’re told in Gen 45:10, Joseph, their ancestor, settled (the clan of Jacob) in Goshen, Goshen is commonly identified as a fertile region in the Eastern Nile Delta. It would then have been near the seat of power in Egypt of the Hyksos Pharaohs, at Avaris. And, close by Avaris was the city of Pi-Rameses which, along with Pithom, is identified in Ex 1:11 as “store cities” that the Hebrews built. So, Moses was, generally speaking, where Pharaoh was.

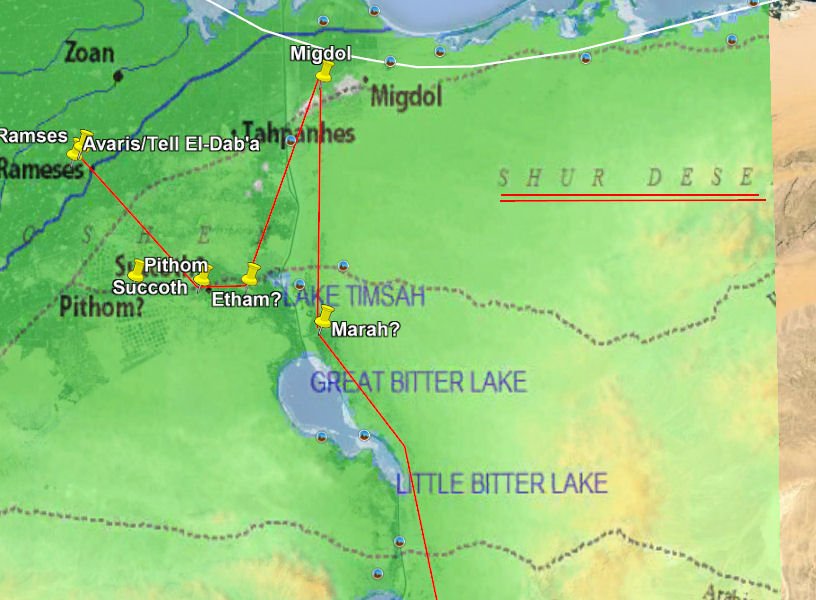

And where was Pharaoh? Likely in Avaris (see Fig 1)[i])

The Timing of the Reed Sea (Yam Suf) Crossing

Many prognosticators of the Exodus route have crossing points of the Reed Sea (Yam Suf[ii]) at locations many days if not weeks away from where the event actually is said to have happened.

We’ll look at the itinerary and its timing in more detail later, but for now you should know that the Hebrews crossed through the Yam Suf not later than a week or 10 days after beginning their journey. Not only that, but their initial stops were still within Egypt proper, not Sinai or any other region.

The consequence of this observation is that when Israel crossed the sea, they were still in Egypt, or just over its eastern border into the Sinai wilderness, as related in Ex. 13. What this means is that, for all intents and purposes, the Yam Suf (3220. יָם yām 5488. סוּף sûp̱) crossing occurred within the region depicted in Figure 1, not in the Gulf of Suez or the Gulf of Aqaba as virtually all non-academic speculators have proposed. It seems that Cecil B DeMille’s portrayal of the sea crossing featuring Charlton Heston is a more powerful cultural icon than the Biblical narrative itself.

The Proximity of Mt. Sinai/Horeb with Rephidim (the Same Place?)

Within the Exodus narrative, when Moses later gets to the rock from which he is going to produce water for the Israelites, he’s at Horeb (Ex 17:6). Immediately thereafter we’re told that Amalek attacks the Israelites “at Rephidim” (Ex 17:8).

Now, of course the author of Exodus could have left out the description of some intermediate travels by the group. But it would have been Moses’ intent, based on his 40 years of shepherding in and around this mountain (Sinai), to lead Israel there, since it was the God of that mountain to whom Moses was in service to bring them out of Egyptian bondage.

So, unless the Exodus author omitted a swath of intervening group trips between striking the rock to produce water, and the attack of Amalek, we have to conclude that Rephidim and Mt. Sinai/Horeb are essentially co-located – one in the same location (or at least the same neighborhood).

This is generally not the interpretation Exodus route speculators assume. Some locate Rephidim tens of kilometers away from their chosen location for the mountain. They may be right. But if they are it is not because the Bible says so.

I’m claiming, based on the text we have, and its absence of any contradicting information, that they’re at the same place.

Now, one of the clues we should focus on is that the Hebrews are attacked in this location by Amalek. We don’t know exactly where the territory of the nation of Amalek was other than it was somewhere in the southern Negev (southern Judah) as the Bible relates a series of skirmishes between Amalek and Israel over the centuries (e.g. 1 Sam 15, 2 Sam 8:11-12, Ps 83:2-7). Amalek himself was a descendant of the Edomites (Gen 36:16). So it would make sense that they were close to Canaan, where the Israelites would settle, and their ancestral home in Edom. If they were hundreds of miles away in the southern Sinai, where the favored narrative locates them, how could they carry out attacks on Israel, practically speaking?

So, if Amalek is in southern Judah/the Negev, and they attack Israel at Rephidim, and Rephidim is adjacent to Horeb/Mt. Sinai, then the mountain can’t be too far from southern Judah/the Negev, right? See Figure 2.

One final consideration for locating the mountain somewhere near the southern Negev is that we’re told that Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law, the Priest of Midian, comes out to meet Moses, along with Moses’ wife Zipporah and her two sons.

Jethro is “in” Midian. He has lived near the mountain for decades. Now, Midian wasn’t a nation with established borders. Rather it was a region located roughly in today’s Southern Jordan and Northwest Saudi Arabia. That region too is near the Southern Negev. So all these factors seem to point to a location for the mountain somewhere in Northeast Sinai/Northwest Arabia, not too far from modern-day southern Israel.

Israel’s Travels Leading Up To The Sea Crossing Narrative

Referring to the narrative in Exodus, beginning in Chapter 12, we find:

[37] And the people of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Succoth, about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides women and children.

And in Ex 13 we’re told:

[17] When Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near. For God said, “Lest the people change their minds when they see war and return to Egypt.” [18] But God led the people around by the way of the wilderness toward the Red Sea. And the people of Israel went up out of the land of Egypt equipped for battle.

So here we see that Israel started from Rameses. And they traveled as far as Succoth, a distance of about 25 miles (Fig 3). Their initial travel path is southeast, toward “the Red Sea” rather than “by way of the Philistines”, or what was known as “The Way of Horus”, a road hugging the Mediterranean coastline from the Delta to Canaan[iii].

Before moving on, we need to take a mental note of God’s instruction not to take the Way of the Philistines. He wouldn’t tell them not to take that (northern) route to get to Mt Sinai unless it was not only a possible route to the mountain, but perhaps the best and most direct. This has serious implications for where to look for Horeb, the location of Mt. Sinai.

Next, we read (Ex 13:20) that they left Succoth and traveled to Etham. Where was Etham? Nobody today knows. But the text says it was at the “edge of the wilderness”, so it was on the border of the Sinai desert. Figure 4 presents a reasonable guess for its location. It is, with Succoth, in the basin of the Wadi Tumilat which traversed the southern Delta and, in the Bronze Age, certainly during the spring floods, would have provided ample water for the exiles.

Today, that Wadi is dry. This brings us to another topic that we should at least be aware of. And that is that the geography and hydrology of the Nile Delta in the late Bronze Age (1600-1200 BC) was quite different from what we find today.

Today’s delta represents 5000 or so years of spring floods since the Bronze Age (3000 BC) carrying their sediment down the Nile to be deposited in the ever-growing Delta. Some experts suggest that the Delta grew by another ten meters into the Mediterranean each year, at least until the Egyptians built the Aswan Dam in the 1960s.

Moshier and Hoffmeier present an excellent summary of the geologic and hydrologic studies that have been performed on the history of the Delta, including through the use of satellite imaging and its analysis[iv].

Figure 4 presents the results of these studies and the work of Manfred Bietek[v] in terms of what the coastline, Nile drainage pattern, and bodies of water in the Eastern Delta looked like 5000 years ago.

The first thing we should note is that current-day Port Said (entrance of the Suez Canal) is some 27.5 miles offshore from the Bronze Age coastline in 3000 BC.

The effect on the Exodus story is simply that today’s landscape for the Nile Delta is not at all the landscape that the emigrating Israelites encountered, either in terms of the coastline of the Mediterranean, or the bodies of water present within the Eastern Delta. Of course, its landscape, some 1500 years after the projected coastline of 3000 BC shown in Fig 4, would have been closer to what we see today, but still dramatically different. After all, it had 2500 years of silting the Delta and annual floods ahead of it in which to transform the landscape.

When trying to understand the path of the Exodus, one simply must take account of the typography and hydrology of the Delta of its time.

The final trip Israel takes before confronting the Egyptian chariots is, strangely, north. In Ex 14 we read (Num 33:7):

[14:1] Then the LORD said to Moses, [2] “Tell the people of Israel to turn back and encamp in front of Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, in front of Baal-zephon; you shall encamp facing it, by the sea.

God instructs Moses to lead Israel by turning back, apparently from the direction they have already come, and camp at Pi-hahiroth, “before”, or in front of, Migdol, between it and “the sea”. (We don’t know where Baal-zephon was. But the name means “Lord of the North”, probably associated with the location of a temple or shrine, further validating that the reverse of Israel’s previous direction was to the north.) The sea mentioned is north of where they are since they are to “turn back”. The most logical candidate for an unnamed sea to the north is the Mediterranean.

The thing that makes this move confusing for interpreters is that it conflicts with the instruction to Israel not to take the northern way of the Philistines (on which Migdol was the Egyptian landmark), and rather take the path of the Red (Reed) Sea, implying south along the Eastern shore of the Gulf of Suez.

As a result of this confusion, interpreters have sought a different location for the Exodus Migdol than the one known in the northeast Delta near the sea.

The Biblical support for this Migdol (see Fig 5) is provided in Ex 14:3:

[3] For Pharaoh will say of the people of Israel, ‘They are wandering in the land; the wilderness has shut them in.’

(The white line in Fig 5 represents a speculation, given the Delta’s expansion rate, as to the approximate location of the Egyptian coastline in 1500-1450 BC.)

We are to conclude from this narration that Israel is still in Egypt – “in the land”; that being told of their whereabouts, Pharaoh concludes that “the wilderness has shut them in” within Egypt. They’re not yet in the Sinai desert (let alone on the other side of it, as many speculate). So Pharaoh doesn’t have far to go in his chariot from (Pi-) Rameses to pursue them.

On this move, Moshier and Hoffmeier comment:

“Migdol can be associated with a fortress of the same name guarding the Ways of Horus in the northwest Sinai along the Mediterranean coast (Gardiner 1920; Hoffmeier 2008b). “Turning back” to the north would put the Hebrew escapees in the midst of the Ballah Lakes, which was the fortified east frontier zone that included the fortified sites of Tjaru (Sile), i.e., Hebua I and Hebua II (Abd el-Maksoud 1998; Abd el-Maksoud and Valbelle 2005, 2011) and Tell el-Borg (Hoffmeier and Abd El-Maksoud 2003). The Egyptian geographical term p3 twfy refers to an area of freshwater and abundant fish, reeds, and rushes (cf. Pap. Anastasi III 2:11–12). The Egyptian p3 twfy has long been linguistically associated with the Hebrew ya¯m s^up or Re(e)d Sea of Exodus 14 and 15 (Gardiner 1947; Lambdin 1953: 153; Hoffmeier 2005).”

The fortress they mention associated with Biblical Migdol is described in a paper by Eliezer D. Oren entitled “Migdol: A New Fortress on the Eastern Edge of the Nile Delta”[vi]. The “p3 twfy” Egyptian phrase in the reference is explained in this article[vii]:

“Etymology, archaeology, historical geography, and geology have helped identify some plausible identifications for Yam Suph. One possibility is the marshy area east of Pi-Rameses, which the ancient Egyptians called p3 twfy “the rushes.” The Hebrew word Suph “rush” is a Hebraized version of the Egyptian twf, “rush or papyrus,” so this identification is very promising. P3 twfy, however, is a marshy region, not a lake or sea (biblical Hebrew, yam), and thus doesn’t fit the story of the “splitting of the sea.”

Therefore, other scholars, such as James Hoffmeier, have suggested identifying Yam Suph with one of the freshwater lakes located between the Gulf of Suez and the Mediterranean Sea that existed in this period.[6]”

In addition, there seems to be good ancient evidence[viii],[ix] for the location of Migdol. So it serves as a reliable reference to position Israel just before their crossing event.

The crucial passage in the Exodus narrative is this:

[15] The LORD said to Moses, “Why do you cry to me? Tell the people of Israel to go forward. [16] Lift up your staff, and stretch out your hand over the sea and divide it, that the people of Israel may go through the sea on dry ground.

Recall, this is being announced to Moses with Israel at Pi-hahiroth, “before” (or in front of) “Migdol”. What “sea” can we find where they are (aside from the Mediterranean)? With Pharoah coming up to them from Rameses, described as “behind” them (Ex 14:19), where would they have felt forced to leave that was restricted by a body of water?

The Crossing

Exodus Chapter 14 goes on to say:

[21] Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the LORD drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night and made the sea dry land, and the waters were divided. [22] And the people of Israel went into the midst of the sea on dry ground, the waters being a wall to them on their right hand and on their left. [23] The Egyptians pursued and went in after them into the midst of the sea, all Pharaoh’s horses, his chariots, and his horsemen. [24] And in the morning watch the LORD in the pillar of fire and of cloud looked down on the Egyptian forces and threw the Egyptian forces into a panic, [25] clogging their chariot wheels so that they drove heavily. And the Egyptians said, “Let us flee from before Israel, for the LORD fights for them against the Egyptians.”

The Bible tells us what happened. God’s chosen tool to remove the obstacle was “a strong east wind” to blow “all night”, pushing water (westward, presumably) to reveal “dry land”. The author is here reminding us of the Gen 1:9 scene in which God separates the waters (chaos, death) to reveal the land (order, life).

Notice also that the phrase “clogging their chariot wheels so that they drove heavily” at least strongly implies that the chariots have been driven into muddy terrain.

The word here rendered “clog”ging is:

- כְּבֵדֻת keḇēḏuṯ: A feminine noun indicating heaviness, difficulty. It describes the stiffness with which the chariot wheels of the Egyptians drove because of the Lord’s intervention on behalf of Israel (Ex 14:25).

This is its only occurrence in the Hebrew Bible. So we’re on our own in its interpretation in this instance. However, I think the “clogging” translation, in the sense of the wheels sinking into a kind of mud flat, makes perfect sense. The previous day, the land their chariots are now trying to traverse was covered in water. Now, temporarily, it’s not. Now, the text reports in a couple of places that the Israelites crossed “on dry ground”. It doesn’t mention mud.

However, a narrow chariot wheel bearing the weight of the chariot and its one or two occupants is going to sink into the recently inundated and saturated land much more than a person walking on that same surface.

Given that God’s method of water “dividing” was a “strong east wind all night”, how should we interpret “the waters being a wall to them on their right hand and on their left”?

In my humble opinion, this phrase is the author’s (“P”‘s) hyperbole[xvii]. If the land is being exposed by a wind blowing (all night) from the east, it is hard to imagine a wall of water on both sides of a land bridge. Water to the West? No problem. But both sides? Probably not. However, God can certainly produce whatever He wants.

But the principal point, I believe, is that this “sea crossing” event is happening someplace in the eastern Nile Delta within its topography and hydrology then present in the 15th century BC. It is NOT happening at some location on the western side of the Gulf of Suez. It is NOT happening on the Western side of the Gulf of Aqaba (Nuweiba is a favorite site because – you know, chariot wheels on the bottom and all). It’s in Egypt. It has only been a week or 10 days since Pharoah let them go! And all of this time they have been milling about within the boundaries of Egypt (“the wilderness has shut them in)“.

So Moses raises his staff, the sea gives way to “dry land”, and Israel passes to its other side. Then:

[27] So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the sea returned to its normal course when the morning appeared. And as the Egyptians fled into it, the LORD threw the Egyptians into the midst of the sea. [28] The waters returned and covered the chariots and the horsemen; of all the host of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea, not one of them remained.

The sequence of events seems to be 1) Pharaoh catches up to Israel near Pi-hahiroth; 2) God protects them from the Egyptians by positioning His cloud and flame at their rear – between them and the Egyptians. 3) Moses calls on God for help; 4) God brings a strong east wind that blows all night; 5) Israel proceeds through what was the sea all the next day and into the night; 6) The pillar of cloud/flame then allows the Egyptians to pursue Israel at some point the same day/night; 7) then, with the Israelites through, the sea returns to its normal “course”/condition, and the Egyptians are inundated “when the morning appeared” following the Israelite’s transit day and night.

So where was it?

We can’t say exactly. The Bronze Age hydrology of the area indicates that there were “lakes” to be crossed if the Israelites were to move south from the area of Migdol, as they were initially instructed to do. The Ballah Lakes are an ancient hydrological feature of the area as is the lake of Timsah. Either of these, or any of the other hydrologically-indicated Bronze Age bodies of water could have been the Yam Suf that Israel and Moses confronted, particularly if the body of water in question connected on its west to a distributary of the Nile during the Spring floods. In that case, it is completely reasonable to envision an inland “sea”[x] getting pushed out into that channel of the Nile to its west by a strong, all-night east wind.

If we look at Fig 6, we see these potential water obstacles on Israel’s way to our assumed Marah[vi] [vii]

Whatever the particular water obstacle was – the particular instance of ‘Yam Suf’ — the Israelites crossed it. The Egyptians didn’t. And the Israelites were free to pursue their Exodus from Egypt to the land their God had promised their father Abraham (Gen 13:14-18)

Subsequent Stops

Marah (Ex 15:22-25)

First of all, nobody knows where any of these stops are. Everyone simply uses educated guesses to locate them[xi].

A brief note about their southerly direction from Pi-hahiroth. Early on (Ex 13:17) we read that God didn’t want Israel taking the “way of the land of the Philistines” (which was due East from their location – “near them”) out of concern that they might encounter some fighting (perhaps nomadic gangs?) and turn back to Egypt out of fear. Instead, He “led the people around by the way of the wilderness toward the Red Sea.” So, it seems quite clear that He intended for them to head south, at least initially, toward/along the Gulf of Suez – the Red/Reed Sea.

But then He tells them to “turn back”, taking them off of their southerly direction.

Now that that diversion is over, it seems logical that they would resume their southerly trek.

What’s the basis for identifying their next stop, Marah, as the location indicated in Fig 6? First, it is 37 miles from their starting point at Pi-hahiroth, and at 2 miles/hr, that’s a trip of about 18.5 walking hours over “three days in the wilderness”. That’s a comfortable pace. Remember, they’re not being chased by Pharoah anymore. His army is drowned. So, Israel has time.

Second, the Hebrew name Marah (4785. מָרָה mārāh) is from a root (4751. מָר mār) meaning “bitter”. The bodies of water it is adjacent to were in antiquity known as the “Great Bitter Lake” and the “Little Bitter Lake” (see Fig 7)

And what do we read about their stop at Marah? Ex 15:22-25

[22] Then Moses made Israel set out from the Red Sea, and they went into the wilderness of Shur. They went three days in the wilderness and found no water. [23] When they came to Marah, they could not drink the water of Marah because it was bitter; therefore it was named Marah. [24] And the people grumbled against Moses, saying, “What shall we drink?” [25] And he cried to the LORD, and the LORD showed him a log, and he threw it into the water, and the water became sweet.

As the figure indicates, the Shur Desert (or Wilderness of Shur) has been associated with the northernmost desert in the Western Sinai. Israel had to pass through its West fringe to head south. And, upon arriving at Marah, they found the water bad – bitter, as the ancient name of these lakes would suggest.

Elim

The thing we know from the Bible about Elim is that it had 12 springs and seventy palm trees. Lots of places claim to be Elim. But one seems to have a few things going for it, not to mention multiple springs. Of course, the number twelve is one of those Biblical numbers. Nevertheless, this place has today, at least seven, and potentially all twelve, freshwater springs. And, of course, it is near the northern tip of today’s Gulf of Suez/Red Sea, so on the path God prescribed.

It’s called Oyun Musa (Springs of Moses) and is located on the Eastern shore of the Gulf of Suez (See Fig 8). This video is an informative description.

Truth be told, there are several viable candidates for Elim along the Eastern coast of the Gulf of Suez. But this one seems to have the most credibility.

Future Stops

The next stops in order after Elim according to Numbers 33:10-15 are:

- “By the Red Sea”

- Wilderness of Sin (Ex 16:1)

- Dophkah

- Alush

- Rephidim (Ex 17:1)

From here it gets even more indeterminant. Most prognosticators base their choices for locations of the coming stops on their choice of location for Mt. Sinai/Horeb (as do I). While some have Rephidim in south Sinai and others have it in Arabia, I am more persuaded by, as indicated above, the proximity of Rephidim to the invasion by Amalek, whose territory is traditionally located in the southern Negev.

It’s hard to imagine any nation attacking the wandering Israelites if they were hundreds of miles away from that nation and its supplies. Apparently, Israel was close enough to Amalek that the Amalekites saw them as a threat and responded accordingly.

This last stop, as we have previously introduced, is the location of Mt. Sinai/Horeb, at least as far as Exodus reveals. Here we have to note that Numbers 33 doesn’t even mention Israel’s stop at the mountain of God. (Instead, it uses the placeholder phrase “wilderness of Sinai” to identify the next stop after Rephidim.) From there it just continues on (from Num 33:16), without so much as a mention of the mountain, to expound on the stops Israel made in its forty-year wanderings before entering Canaan (via the plains of Moab by the Jordan at Jericho – Num 33:48-49).

So where were these post-Elim stops? Who knows? There’s just no way today, without the recovery of some archaeological inscriptions that claim Israel’s presence, to identify them. Again, if your Mt. Sinai is St. Catherines in the southern Sinai, you can fill them in with some plausibility to get you there. Same if your Mt. Sinai is in Arabia (say at Jabal El Lawz/Maqdal).

Rephidim/Mt. Sinai/Horeb

Figure 9 depicts some features of northeast Sinai including the area of the “wilderness of Paran” (/Etham).

The wilderness of Paran comes into play throughout the Tanakh. Dt 1:1 refers to it and several other landmarks in identifying where Israel embarked on their final journey in the wilderness up to the Promised Land.

[Dt 1:1] These are the words that Moses spoke to all Israel beyond the Jordan—in the wilderness, on the plain opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Hazeroth, and Di-zahab. [2] (By the way of Mount Seir it takes eleven days to reach Kadesh-Barnea from Horeb.)

We have several place names mentioned here. First, we know Israel was in a “wilderness”. And their location was “on the plain opposite Suph”. Different Bible translations handle the term “Suph” differently. Its dictionary definition is:

-

- סוּף sûp̱: I. A proper noun designating the place Suph, near ‘Mount Horeb’ (NASB, NIV, Dt 1:1).

- Red [reed] from sûp̱ (5488), a designation for the Red Sea (KJV, Dt 1:1).

We see that it is the name of a place as far as (e.g.) the NASB and NIV are concerned (note its capitalization, as a place name, in these translations). But the KJV translators focused on “reed/red” and reflexively filled in the missing “sea” to get “Red Sea”. (Interestingly, the NKJV backs off its predecessor’s “Red Sea” translation and substitutes “Suph”.)

The plain they’re on is “between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Hazeroth and Di-zahab.” We don’t know where these places are (though there is a modern-day Paran in southern Israel). But the image we get is of these places surrounding Israel’s location on that plain.

I think it should be at least considered that the area being referenced here is the red sandstone formations around Mt. Seir in southern Jordan (see Figure 10). It’s even possible that this red sandstone is the reason for the name Edom – “red” (though the traditional explanation is that its founder, and Issac’s son Esau, not only had a red color at birth but later sold his birthright to Jacob for some red stew, causing him to be renamed Edom. Gen 25:30)

And then we get a strange, parenthetical statement in verse 2. It literally reads that it takes eleven days to travel from Horeb (wherever that is) via Mt Seir (and we do have some idea where it is) to get to Kadesh-Barnea (and we have a decent idea of its location).

Picking A Location for the Mountain

Let’s review.

Moses has brought Egypt to a location he knew well in Midian where he had encountered the burning bush and the One God. It’s in His service that Moses has been enlisted and for Whom he serves. The area of Midian was south of Moab, now southern Jordan and northwest Arabia (though no precise dividing line can be identified). He’s taking them to meet with their God and to receive His further instructions for them.

The mountain of God (Sinai/Horeb) is in or adjacent to “Midian”, as Moses was shepherding Jethro’s (the Priest of Midian) sheep when he first encountered God at that mountain. So, the mountain is “shepherding distance” from Jethro’s camp in Midian[xii]

The other piece of scriptural data we need to take account of is the narrative of Moses’ travels from his location in Midian to and from Egypt. The most significant of these I believe is found in Exodus 4:19. Here, God instructs Moses to return to Egypt to confront Pharaoh for the Israelites because “all those who were seeking your life are dead.” Moses responds and packs up his family (his wife and children) to make the trip.

The sense of this I get is that the trip from their location in Midian (again, close to the mountain of God) was not so challenging that Moses considered it a risk or hardship for his wife and kids. To me, this infers that their path out of their location in Midian was not harrowing.

Later, Moses sends her and the kids back home to Midian – by themselves (Ex 18:2-4). This also indicates the trip wasn’t overly challenging. Apparently, they could be provisioned with food and water to carry with them that would last until they returned home or at least between water and provisioning sites. And it indicates that she, like Moses, knew the way and its landmarks.

We should also understand the term “Horeb” and how it may be distinguished from the nearly-synonymous “Sinai”. Conventional wisdom today is that Horeb and Mt. Sinai are the same thing/place. But there is a linguistic argument that the Hebrew 2722. חׂרֵב ḥōrēḇ refers to a region or territory, and a god-forsaken one at that.

2722 חׂרֵב ḥōrēḇ is derived from:

- חָרֵב ḥārēḇ, חָרַב ḥāraḇ:A verb meaning to be desolate, to be destroyed, to be dry, to dry up, to lay waste. Two related themes constitute the cardinal meaning of this word; devastation and drying up. Although each aspect is distinct from the other, both convey the notion of wasting away.

חׂרֵב ḥōrēḇ is just one of a series of words derived from H2717, including 2721. חׂרֶב ḥōreḇ (noun: heat, drought, dryness), 2720. חָרֵב ḥārēḇ (adj: dry, desolate, wasted), and 2718. חֲרַב ḥaraḇ (verb: utterly destroy, be laid waste). Van Brenk? [xv] also comments (quite cryptically) on the linguistic significance of Horeb’s trailing “b” consonant – the Hebrew letter “bayt” – as evoking the idea of a dwelling place (as the consonant has the same sound as the Hebrew word 1004. בַּיִת bayiṯ, meaning house or dwelling place).

So, while most translations equate Horeb with a unique location, sometimes encouraging the reader to conflate it with “mountain of God”, or simply calling it “Mount Horeb”, the idea the original language is conveying seems to be that Mt. Sinai was located within this horrible, dry, desolate area known as Horeb. And certainly, all the areas commonly considered for the site of the mountain (Jabal Al-Lawz, Jebel Musa/St. Catherines, Mount Seir, and Har Karkom) perfectly fit that description.

Nevertheless, some of the Bible’s “Mount Horeb” texts are quite unequivocal, whatever their origin and understanding of the original meaning of that proper noun. I just think it is quite strange and a bit dissonant to equate a “dry, desolate, wasted, laid waste” Horeb with the mountain where God gave all humanity His presence and His instructions for living, and where it was believed He resided on earth.

My speculation is that Horeb was the area surrounding today’s Har Karkom (see Figure 11). It is one of the candidate Sinai sites that, for our purposes, adequately (and I would claim best) fits the description that we find in the Bible and is certainly quite close to both the Amalekite’s location as well as the assumed Midianite region encompassing Southern Jordan and Northwestern Arabia.

Sinai-to-Moab

But so far, we only have Israel at the mountain. They’ve still got to (eventually) get from there to Moab, the place the Bible identifies as (Num 33: 49) “they camped by the Jordan from Beth-jeshimoth as far as Abel-shittim in the plains of Moab.”

I recently ran across a video presentation by Dr. Deborah Hurn of Avondale University, Department of Theology and Ministry entitled ‘“Eleven days from Horeb”: Deuteronomy 1:1-2 and Har Karkom‘ (see also A Hydrological Model of the Biblical Regions of the Exodus and Wanderings) dealing with the problem we discussed re: the mysterious Dt 1:1-2 terminology and its implications for the location of Horeb.

Rather than wondering where Horeb is, Hurn has simply concluded (as I have here) that it is the area surrounding Har Karkom, in northeastern Sinai, and that that mountain is, in fact, the Biblical Mt. Sinai.

However, she offers some very ground-breaking insight into the meaning of the verses in question. To review, modern translations of these two verses read something like:

[Dt 1:1] These are the words that Moses spoke to all Israel beyond the Jordan in the wilderness, in the Arabah opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Hazeroth, and Dizahab. [2] It is eleven days’ journey from Horeb by the way of Mount Seir to Kadesh-Barnea.

In our common English translations, verse 2 here acts as a kind of parenthetical statement unrelated to v1. First, she offers a different translation provided by Robert Alter in his “The Five Books of Moses: A Translation With Commentary“, 2004. Alter renders these two verses as follows:

These are the words that Moses spoke to all the Israelites across the Jordan in the wilderness in the Araba opposite Suph between Paran and Tophel and Laban and Hazeroth and Di-zahab, eleven days from Horeb by way of Mt. Seir to Kadesh-Barnea.

The purpose of this description is twofold. First, it describes the location in Moab of Moses’ speech to Israel relative to Horeb. It’s saying that to travel from Horeb to the location of the speech “across the Jordan”, would take eleven days. It is NOT saying that it takes eleven days to travel from Horeb to Kadesh-Barnea.

In fact, the presence of Kadesh-Barnea in this description is distracting because, as we’ll see, Israel would not have to travel to Kadesh-Barnea to get to Moab from Horeb. Kadesh-Barnea is mentioned because, as was typical in the biblical period, travels were described by referring to routes taken that were identified by their terminus locations (whether those terminus locations were literally part of the described travel or not.) In this instance, Kadesh-Barnea is one terminus of a route in use then called the “Way of Mt. Seir”, which traversed from Kadesh-Barnea (“W. Mt. Seir”) in the west to Tophel (“E. Mt. Seir”) in the east, on the southern Transjordan plateau east of the Rift Valley. “Mt. Seir” (in this v2 translation) isn’t talking about a mountain. It’s talking about an east-west route of the same name.

Second, it points out the sad irony that Israel’s trip from the mountain to Moab should have taken eleven days. Instead, it took them forty years and the loss of an entire generation. Effectively, Deuteronomy’s author is throwing Israel’s history of unfaithfulness back in their face, saying: “This could have been so simple if you had just obeyed the LORD. Instead, you’ve suffered in the wilderness for forty years to finally get to this place that God promised He would bring you to forty years ago.” Ouch.

The path (of which the linked video, above, explains its rationale and details) from Horeb to Moab across the Jordan is depicted in Figure 11.

Read in this way, Dt 1:1-2 claims Horeb is eleven days journey from the location of Moses’ speech. This route from Har Karkom (Hurn’s [and our] assumed Sinai) to the site of the speech in Moab takes roughly eleven days and is based on established routes that run between water sources not more than a day’s journey (Hurn claims an average of 30 Km or 18.6 miles) apart. So, if we’re looking for Horeb, Har Karkom is, I have come to believe, the prime candidate. Without knowing the location of all the water sources in the region, it’s hard to propose other possible candidates with any certainty or credibility.

The other criteria we had was that the mountain should be “grazing” or “shepherding distance” from Jethro’s camp in Midian. If we think of Midian as northwestern Arabia, running along the eastern shore of the Gulf of Aqaba, then I’d say it’s too far away to be “shepherding distance”. However, if Midian extended farther north into today’s Jordan into the area typically associated with Edom, then, yes, Har Karkom could in fact be “shepherding distance” away from Jethro’s camp. This would also locate Jethro’s camp far enough north that one would not have to travel south around Eilat and down into modern day Arabia in order to get from Egypt back to the mountain and Jethro’s camp, making that trip at least feel more plausible for Moses’ wife and children to do on their own.

So How Did Israel Get From Egypt to Horeb?

We mentioned earlier that no one knows where virtually any of the sites named in either the Numbers 33 itinerary or the Exodus 16, 17 itinerary are located. However, one thing we do know is that the text does not mention Israel needing water during their trans-Sinai Peninsula trek until they’re at “the rock at Horeb” (Ex 17.6). So, they must have followed a path in which there were water sources spaced approximately one walking day apart.

We also know that there was an ancient trade route traversing the peninsula from the Nile Delta to Southern Canaan that was south of the coastal, Way of Horus route, called The Way to/of Shur (see Figure 12; blue route).

In Figure 12 I have fudged the Israelites route (in green) from Elim north to intersect with this “Way to Shur” route, which they likely followed for a time until once again turning southeast to arrive at Horeb, no doubt following a path connecting a series of water sources. Such a route is only plausible. No one really has any proof for any particular route.

Conclusion

We’ve ruled out the popular candidates for Horeb/Sinai other than Har Karkom by paying attention to the text. We convincingly (I believe) established that the Reed/Red Sea “crossing” occurred in Egypt[xvi], not crossing either Gulf of the Red Sea. And, perhaps most importantly, through Dr. Hurn’s work, we seem to have “cracked the code” on the enigmatic Deuteronomy 1:1-2 laying out a well-researched route from Har Karkom to Moab across from Jericho that perfectly matches the text.

Is this the correct interpretation? It all seems plausible at the very least. But, as initially mentioned, any proof will have to wait for additional material evidence (or, perhaps, an as-yet undiscovered ancient scroll spelling things out a bit more clearly.)

[i] Throughout this study I will be presenting maps from Biblemapper 3.0 overlaid onto Google Earth images to clarify the locations being discussed. The process of accurately overlaying such maps is not without its challenges. But the resultant figures should nonetheless provide you a reasonable framework for analyzing the geographical context.

[ii] I once thought that the name “Yam Suf” narrowed down the list of candidates for the crossing site to the region of the Nile Delta. Unfortunately it does not. The name is applied to the marshes in the Delta, to the Gulf of Suez, to the Gulf of Aqaba, and to the main Sea itself.

[iv] Moshier, Stephen O and Hoffmeir, James K, Which Way Out of Egypt? Physical Geography Related to the Exodus Itinerary

[v] Bietek, Manfred, Avaris the Capital of the Hyksos; Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab’a. Figure 1, p3

[vi] Oren, Eliezer D, Migdol: A New Fortress on the Edge of the Eastern Nile Delta

[vii] Ben-Gad HaChoen, Dr. David, The Yam-Suph in the Transjorden?

[viii] Copilot: The Antonine Itinerary, a Roman road map, places Migdol 12 miles south of Pelusium. The site is believed to have been near Tell es Samut, which was known by the Egyptian name Samut. This Migdol likely served as a watchtower along the main coastal road from Palestine, which was called “the way of the land of the Philistines”

[ix] Copilot: According to a map of the Way of Horus, Migdol is located east of the Dwelling of the Lion, which has been identified as Tell el-Borg near the north coast of the Sinai Peninsula and the estuary of the Ballah Lakes1.

[x] Lakes in antiquity were often referred to as “seas”. The water labeled ‘Ballah Lakes’ extended over an area of 18-20 sq mi. The ‘Sea’ of Galilee covers an area of about 66 sq mi. We call it a lake.

[xi] However, everybody is interested in locating their place as thee place, for economic and other reasons. So, you’ll find as many “Springs of Moses” in Sinai and Arabia as there were purported to be springs themselves. And, of course, everybody’s got their favorite Mt. Sinai.

[xii] Where Did YHWH Come From?

[xv] Van Brenk, Ron, Why Horeb is not a Mountain: and definitely not Mt. Sinai

[xvi] Kenneth Kitchen in his 2006 book “On the Reliability of the Old Testament”, p261, seems to agree with me, locating the yam suf crossing just north of Lake Timsah (in Egyptian “crocodile lake”) and south of the southernmost Ballah Lake.

[xvii] In “The Exodus Narrative According to the Priestly Document” Thomas Roemer points out that Exodus contains two ‘crossing’ narratives. He says:

“Exod 13,17-14,31 is one of the classical cases where two independent

documents can easily be isolated: an older account where YHWH pushes the

sea back, like an ebb tide, and the Priestly account, where the sea is divided

and the Israelites cross the sea, the waters forming a wall on their

right and on their left. Interestingly, the fact that there were two different

biblical accounts about the miracle is still remembered in the work of

Artapanus, who wrote in the second century BCE and who reports that

there existed two competing traditions about the crossing of the sea among the Jewish communities in Egypt which correspond roughly to the two accounts mingled in Exodus 14.”

So we have a later “P” to thank for the “wall of water” imagery.

Leave a comment